When I was 15, I had a relationship with a man I’d never met.

I can still hear the click-dial-fuzz of America Online booting up, the modem’s pulse struggling to connect; and when it finally took, anticipation burned through my chest until I heard that satisfying announcement: You’ve. Got. Mail.

How I lived for those words, the tiny mailbox icon waiting to be checked. Inside, messages arrived for Veronica, Helena, Sabrina — and then there was me. More often than not, I had an email from somebody; with a little luck, I had an email from Tony.

***

Logging on to AOL was the first thing I did when I got home from school, blasting Bikini Kill while debating the greatness of obscure indie bands across a maze of message boards and chatrooms. AOL brought everyone online, together, for the first time, and I befriended people across the country who liked the same things I did. They were faceless people, people behind monikers like BeYerMama, xXRaySpeXx, or my own disturbing handle, ScabiesGrl, repurposed from a Cold Cold Hearts lyric.

Armed with a keyboard and an Ethernet cable, my friend Marie and I had quickly begun testing the limits of what we could accomplish online. Nearly 15 years before the film “Catfish” coined the term for tricking someone on the Internet, it was just what we did: whip up fake screen names and personas with a click. And for two bored girls living in North Carolina, AOL was a crack in the biosphere of our hometown, a window to another world, and we made a run for it.

***

I can’t remember what Tony looked like, but I know that he sent me just one photo. Was it a group shot with co-workers, a snapshot beside the Golden Gate Bridge? I think he lived in San Francisco, or maybe Los Angeles. What I remember most about Tony is that I didn’t find him, he found me.

I’d posted on a message board seeking obscure recordings of a short-lived West Coast band, and a woman named Elena responded, offering to make me a mixtape, no problem. She thought it was cool that I was so young and into fun music and mailed the mixtape, and more mixtapes, stickers, and buttons. Soon we were chatting regularly, even though Elena was in her mid-20s. She worked an admin job in Oakland and her boyfriend was planning on proposing.

I was the girl with pink hair who lived with her dad and wrote abortion poems in creative writing class. I’d never had an abortion, but this sort of provocative behavior, statement-making, was part of my regular act back then. I was restless, itching to start living. So when Elena said she’d told her friend Tony about the punky-poet high-schooler, and that he found me interesting and wanted to chat with me too, I told her sure. I didn’t see why not.

***

Hordes of musicians and industry people frequented those AOL message boards, which made it easy for Marie and I to contact them. We sent haiku, and other absurdist declarations of fangirlism for their flash-in-the-pan bands, many of whose names wouldn’t register today.

But safe behind fake identities, invented screen names, we conducted full-fledged romances with a handful of male musicians by pretending to be English majors at colleges in nearby towns, luring them with scantily clad photos of women we’d pickpocketed from the web. Because they needed constant ego-stroking, musicians made easy targets. I never felt guilty. At one point, I was chatting with a singer in Canada who wanted me to join him in his hotel on the Chapel Hill stop of his upcoming tour. We got so deep into catfishing another singer that he once showed up at the UC Berkeley dorm room where we claimed to live.

“Outside, I called your name,” he later emailed, “but no one ever came.”

***

Tony arrived some six months after my heart had been wrecked by Jeff, the first boy to show me his penis, in a Buick behind the church on Friendly Avenue, the first boy I claimed to love. I was 14 then, but with a chest ripped from a magazine; I’d quickly learned what men wanted from me. It had already been decided for me, which was the reason catfishing had ultimately become so fulfilling: toying with a man’s desire over the Internet was one of the only means I had to feel powerful.

I can’t recall when Tony first instant-messaged me, but I can surmise how our bond likely cemented: music. Late nights behind our computer monitors talking favorite Pavement songs or a shared love of Jawbreaker’s “24 Hour Revenge Therapy.” Music was my passion, the way in.

***

Like Elena, Tony was in his mid-20s, which thrilled me because it made our relationship risqué. I was lonely, and a teenage girl’s loneliness can be dangerous, which was why Marie and I decided to form a band. She clumsily attempted bass; I struggled to learn chords on the red Fender I’d begged my father to buy at the pawn shop. We called ourselves Peter. We were terrible.

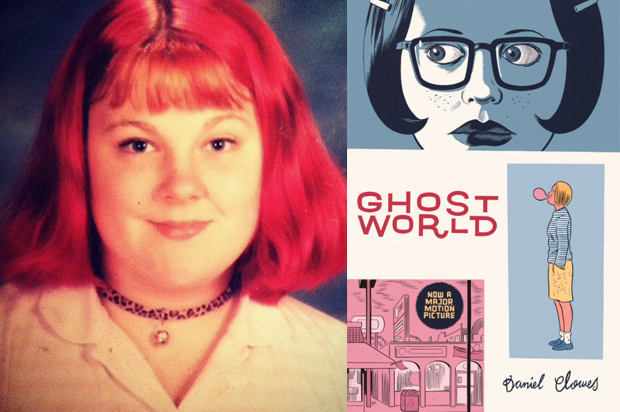

Some Saturdays Marie drove over, though she lived just a few blocks away, and we’d hammer out songs on my bedroom floor. Afterward, we’d steer her car to the bookstore, or the downtown record store, where the amiable mid-30s clerks said we reminded them of the teenaged troublemakers in Daniel Clowes’ graphic novel “Ghost World.”

“It’s about two bored girls who do weird things to men,” my favorite of the clerks informed me.

I’d never heard of the book, and this was years before the Thora Birch adaptation, but I remember smirking, feeling flattered, and then thinking: You have no fucking clue.

***

School was spiritless and bland, but talking to Tony was fun, and I often skipped class just to chat with him. He was three hours behind in California, but he’d log on to AOL as soon as he got to work, noon on the East Coast.

I emailed him copies of my poems and expressed writing aspirations. I detailed my weekends with friends, cruising town, a bottle of Two Fingers tequila passed between us. Already we were hanging out with an older crowd: goateed ne’er-do-wells in their 20s and 30s who we worked with at drugstores and restaurants. Languishing inside their apartments, we watched them play video games from a nearby sofa while we chain-smoked and awaited our turn with the blunt. I loathed those men and those nights — the epitome of feeling stuck. I preferred attending shows in Chapel Hill with Marie. We’d scream down I-40, scream during the show, scream all the way home, our town quiet and dark, Marie’s the only car on the road.

I told no one about Tony. Not even Marie. I liked having a secret this illicit — a crush on an older man I’d met online. The crush wasn’t even the hardest part to admit, or the worst, which was that I’d started to suspect Tony liked me back.

***

With their monster trucks and unearned pompousness, no hometown boy stood a chance of enticing us. We were big league: we’d infiltrated musical circles, as ourselves and under aliases. At night, undercover, I was having cybersex with musicians a coast away. Marie never went this far, it was only me, and I was still a child. I didn’t even have a driver’s license; when I needed to escape, Marie chauffeured me everywhere.

One night while gulping Shirley Temples at the Applebee’s up the street, Marie and I left this poem for our waiter on the back of a receipt:

You hand me my apple

pie and say “Sweets for

the sweet” and I

know that you are

wrong: night after

night on the job and

just a poem for a tip,

making your rounds

with water in aprons of

silk and soot and

other sharp things,

and what is this—

this thing we have?

“Is it more than

chicken finger love,”

you ask yourself

as plates crash beneath

you, tears filling

your Applebee heart.

After an antic like this I’d cackle wildly inside Marie’s getaway car, then she’d drop me off outside the second-floor apartment I shared with my alcoholic father. I’d hop onto AOL immediately, my body vibrating with urgency, a palpable desperation to be seen.

***

Yet for all our online meddling, we were naive when it came to being preyed upon. We started corresponding with an aging record label exec with a mansion in Southern California who proposed an internship for Marie and me — only if we were OK with sleeping in the basement and without a peep to his wife. I actually broached the idea with my father, who looked at me sideways.

Marie and I never knew if he was joking about the basement or not, how he said he’d gorge us with jelly beans, rolling them under the door for us, one by one. Then one day he offered to mail us disposable cameras so we could snap pictures in our underwear. If he liked what he saw, he said, he was willing to put out Peter’s first single.

***

Tony was never inappropriate so much as he was wistful, saying things like, “Why can’t you be older?” But even in revealing this wish, he was casual, never lecherous. I was a pal. We discussed music and movies. He made recommendations; I sought them out from the video and record stores immediately.

And still a fuse had been lit; our exchanges were laced with a humming electricity. We had the fluid, easy banter of old friends with nicknames and time-worn jokes, not the stilted conversation between a different teenage girl and grown man.

Once, he told me that he and Elena had discussed a visit to California. “Would your dad be OK with that?” he wondered.

“Obviously, you’d stay with Elena,” he made sure to add, and I imagined meeting Tony at her apartment. How we’d eat pizza on the porch and that Tony would pin me against the wall and kiss me once Elena stepped away to refill our drinks. The idea of a visit excited me some days; others, I felt nauseous.

***

In the meantime, Peter was flailing. We didn’t have talent as musicians, just a talent for harassing them. Still, Marie and I spent hours in my room banging out songs, including “axemen” by Heavens to Betsy, Corin Tucker’s precursor to Sleater-Kinney:

here we go axemen here we go

at the pep rally i stole the show

wearing our purple and our whites

hey look around there’s so much white

do you wanna live this teenage dream

the punk white privilege scene

oh quarterback i’ll steal your axe

and cut it out of here

***

Tony had an on-again, off-again girlfriend named Alyssa. I knew she was over on the nights he didn’t meet me online, that they were back on again.

“Did you have sex with her?” I’d brattily pry the next time we chatted.

He never answered, but he never told me that I should flirt with someone my own age, either.

***

A few times I let my favorite in my coterie of musicians call me, always in the middle of the night, always while he was drunk. I kept my hand on the receiver of our landline so I could pick up immediately, so the ring wouldn’t jar my dozing father.

He was the only one I ever met, on the North Carolina stop of his tour. I’d led him to believe I was 21, a library sciences major. During the show, he guzzled Red Stripe, a beer I’d never heard of but I liked its stout brown bottle. I flagged down the bartender. “Red Stripe,” I announced, and without a second take, he placed the chilly glass in my hand. After all, what would a 15-year-old be doing out on a school night? Marie’s mom hadn’t let her attend, so I’d convinced my friend Cheryl to drive to Chapel Hill so I could chat up the musician. If I looked like a child, he never mentioned it. Under the table, he’d even initiated a game of footsie. Before taking the stage, he ran his hands through my hair.

My heart hammered. All I could think was: I’m 15.

***

It was February when Tony told me he’d received a job offer in Amsterdam. The air was icy, the afternoon grey, and I’d skipped school to spend the day with him again. “Job offer?” I typed.

He’d been unhappy, he said. A rut. Things with Alyssa were off-again. This was his chance to start over. In Europe! “I have to take it,” he said.

I was stunned. I’d never met this man. Most of the time I knew I shouldn’t be talking to him. It was inexplicable that I already missed him, but I did.

***

It happened fast, Tony’s leaving. But first he asked for my phone number, claiming he’d call me from Amsterdam. I waited days for the phone to ring. I told myself he was taking his time, settling in. A night before his flight, he’d emailed me lyrics to the song “I Just Do” by the twee-pop band Go Sailor. He said it was how he felt about me:

I dropped a penny and you picked it up

you want to be something when you grow up

you make me laugh and you don’t even try

you say that sometimes you just like to cry

I’m in love with that

I’m in love with you

***

Maybe I didn’t tell anyone about Tony because they’d question whether he really existed. I wondered sometimes. About Elena, too. Maybe I was catfishing while being catfished also. The probability was high — Marie and I were clever but our techniques were far from sophisticated. With suspicion and a little ingenuity, anyone might’ve snuffed us out.

Tony never phoned from Amsterdam, and I never talked to him again. I was legitimately sad for a few months, during which Elena’s boyfriend finally proposed, and we talked less and less, and eventually not at all.

It’s easy to think now it had all been a ruse. But Elena’s mixtapes had arrived, and with a return address. At least I knew someone was on the other end, even if I never quite knew who.

***

Then, I got caught.

How, I’ll never know, but one night the Canadian singer confronted me — he knew my real name and my hometown and threatened to call my parents until I begged him down, even though I knew he wouldn’t — couldn’t — explain too much without exposing his own culpability or risk me blabbing about the Chapel Hill hotel room where he’d wanted to bend me across his knee.

I sometimes wonder if these men secretly knew that we were teenagers hiding behind facades, merely phantoms in pajamas, snickering wickedly. In those days the Internet was the Wild Wild West. It’s a miracle it never swallowed us.

***

In the fall of my junior year I failed my driver’s test three times before passing. Marie was a senior applying to colleges. I was still bored, but having a license was by far the most fulfilling of adolescent victories. At the Toyota lot with my father, I chose a used Corolla, and later strung furry pink dice on the mirror.

So much about being young was biding time, uncovering the escape routes, crawling on hands and knees toward any sliver of light. Because of that, I never took driving — nor the power and independence it offered — for granted. AOL was how I’d once survived, but I was already speeding toward newer dangers and, finally, I had another way to get there.