Jim Jarmusch’s new documentary about Iggy Pop and the Stooges, “Gimme Danger,” is both a truly historical account and a labor of love. It’s not accidental that you see Jarmusch’s face in an early frame, at the beginning of a take, acting as a human clapper. His visual voice and passion for this music is present throughout the film. That’s not necessarily a bad thing. Rock and roll is at its core and by default not meant to be neutral, but Jarmusch has done an excellent job at steering the narrative as objectively as possible.

It’s important to remember that “Gimme Danger” is the story of Iggy Pop and the Stooges. It’s not an Iggy Pop biography, so people who want dirt on, say, the years with David Bowie in Berlin will be disappointed. But there’s so much material here that you would have to want to be dissatisfied.

Jarmusch’s film begins deep: The baby pictures come out, and Iggy (aka Jim Osterberg) takes us back to his childhood, living in a trailer with his parents in the suburbs of Ann Arbor, Michigan. But Jarmusch is smart, and every scene, every line has been carefully chosen: There’s no self-indulgent rambling here. He has let Iggy and later his bandmates tell the story in their words. Luckily, Jarmusch got to talk to everyone who was in the Stooges before they died (short of original bassist Dave Alexander, who passed away in the ’70s). There’s almost zero fat. The choices made in the editing room must have been brutal.

But the results created a storyline that’s compelling yet economical. If you don’t know anything about the history of the Stooges, you will get everything you need to know. And even if you think you know everything already, chances are high you will still walk out having learned something you didn’t know or having gleaned a new insight into the band. For example, Osterberg’s first band, The Iguanas, benefited from the same teen dance club network that Bruce Springsteen’s early bands did. (In this case, the local club was called The Pony Tail.) Or the affectionate way Osterberg describes how his parents, tired of young Jimmy playing drums for hours in the living room of their trailer, gave him the master bedroom instead.

The fact that Iggy Pop started his musical life as a drummer occasionally feels like a side note in previous historical accountings of the Stooges. But Jarmusch knows better, and so that thread pulls you through the beginning of the film until the point at which Iggy shares the moment at which he decided to give up the drums: “I got tired of playing behind someone’s butt all the time.”

But those years that Osterberg was behind the drums directly affected the later sound of the Stooges more than anything else. He doesn’t say it. Jarmusch hasn’t written it on the screen (a device he thankfully used only a couple of times); he just shaped the film in such a way that it’s the only conclusion you can reach.

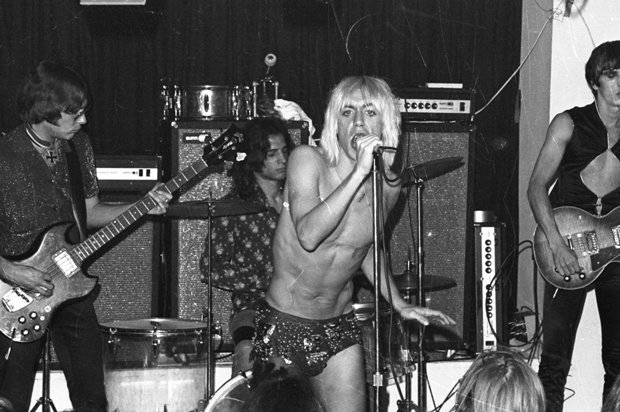

This is the group of artists who came of age in an era before everyone had a photographic device in their pocket, which presents a serious challenge to a documentary filmmaker. If there’s very little source material, then what on earth do you show on screen? You can’t just have the camera on the narrator the whole time.

Jarmusch has worked with whatever early footage exists, because you have to have those visuals, no matter how low in quality, in order to make the point of how jarring and different the Stooges were in that particular period of time. Jarmusch has taken it one step further by successfully employing various cinematic techniques to either enhance or distort the footage. If the audio is usable, he has figured out how to put it front and center while still giving the audience something to look at. A lack of actual band footage often has been replaced by stock footage from the era or other images and clips that make the point. Some of the sequences are a little jokey, but they’re jokey in the same spirit that the Stooges were.

The film has a simple structure of historical narrative that is absolutely appropriate, while not skipping anything important. Again, no diehard will walk out muttering under his or her breath that Jarmusch forgot anything. That early history is bleak. After their early triumph in getting signed by Elektra Records — yes, Danny Fields (the A&R manager who later ended up managing the Ramones and the subject of a documentary) is on camera, providing his role in the Stooges history with his now-trademark fervent candor, including his excitement at discovering and then signing them while on a trip to Ann Arbor to sign the MC5. His sadness and disillusionment when the man holding the checkbook turned to Fields and said, “I didn’t hear a thing,” after listening to the new songs the Stooges were working on for their third album. The camera zooms in on the sadness that’s still reflected in Fields’ eyes over that disappointment; he doesn’t have to say anything else because Jarmusch has made you feel it with him.

No one tries to sugarcoat the role that drugs played in the band’s unfortunate series of ups and downs and the path to obscurity that it led Ron and Scott Asheton and then James Williamson of the Stooges. Williamson later made a career for himself as a studio technician and then a computer programmer and then later as Sony Music’s vice president of technical standards. But things didn’t end anywhere near as well for the Asheton brothers. No one on screen (or off, in the case of Jarmusch) tries to make it sound any better than it was. No one makes any excuses for it; no one — not the filmmaker, not his subjects — tries to avoid the subject.

The bleakness of this particular section makes the transition into the story about the almost accidental reunion in 2003 feel that much more satisfying. Mike Watt, who ended up playing bass for the Stooges, tells the story from his perspective, which is always unique. He tends to see life through a filter that’s equal parts direct gruffness and equal parts wide-open heart.

And he takes the audience through the story, about how J. Mascis (the only glaring omission in “Gimme Danger,” from an interview perspective) brought Watt to play a couple of Stooges covers while he was recuperating from a life-threatening illness — which transmuted into a set on the J. Mascis tour, which then became a tribute set at the 2002 All Tomorrow’s Parties festival at UCLA, curated by Thurston Moore. At some point, Iggy caught wind of it and, while working on a Stooges tribute album, decided that no one would play those songs better than the actual band and made the phone call.

The pacing in this section is key: Jarmusch has not offered too much detail, but just enough and the right detail. And it build and builds until you get the feeling of what it was like as a fan to think that one of your favorite and most influential bands, a band you never ever thought in a million years that you’d get to see play live, was getting back together. And then there’s that grainy Coachella video that you probably watched a million times before something better came out because you just had to have proof for yourself: The Stooges were back.

Jarmusch could have ended it there, but the viewer is brought back to Michigan one more time, where Iggy tells the story of being a kid in high school and living in a trailer with his parents, and how a group of popular kids came over one day and tried to turn the trailer over. Iggy shares how he always wanted to get revenge on those guys: “I will bury them,” he says, and the next thing you see is Iggy in a tux at the podium in the Waldorf-Astoria Ballroom, when the Stooges were finally inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2010, after being nominated no less than 11 times. Iggy graced the crowd with two middle fingers raised and made sure to point out that Ron Asheton and Dave Alexander would have loved to be there and that Ron was pissed off that it didn’t happen while he was alive.

The Hall of Fame induction would be that moment of redemption and affirmation and validation before the fade-out and the images of Dave Alexander, then Ron Asheton (who passed away in 2009), Scott Asheton (2014) and saxophonist Steve Mackay (2015) appear on the screen. And you’re faced with the grim reminder that as great as it is to have these kind of films and have the great rock and roll legends immortalized, it’s only happening right now because both the artists and their fans are aging out. There, too, Jarmusch has ensured that the band’s legacy is recorded correctly and bone-chilling accurately. Of course “Gimme Danger” isn’t going to have a fairy tale ending. It’s the story of the Stooges, after all, who were doomed before they barely got started.

The one thing that Jarmusch hasn’t done well in “Gimme Danger” is an awkward section where he attempted to document and codify the band’s impact on rock ‘n’ roll. He started this by having Danny Fields note that the reason the four members of the Ramones met was because they were the only people in their high school who all liked the Stooges, but it goes downhill from there. On the one hand, it’s logical that Jarmusch felt that it was important to document the band’s influence. But this section feels rushed and almost forced and could have used a few more interviews to back it up. It’s the one disappointing moment in an otherwise very strong 108 minutes.