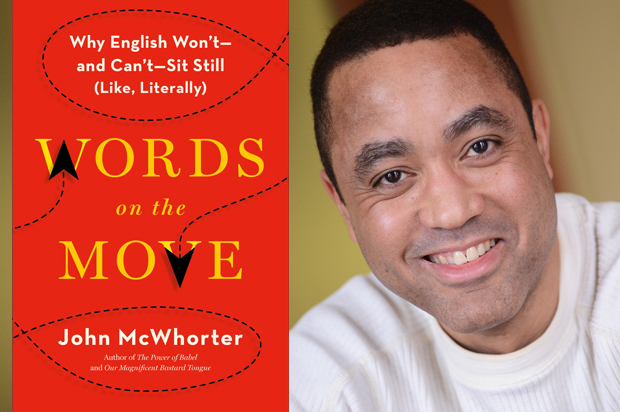

Why does language change? Why do we get so upset when it does? And is there any way to stop it? These are some of the questions linguist John McWhorter tackles in his fascinating new book “Words on the Move.”

Subtitled “Why English Won’t — and Can’t Sit Still (Like, Literally),” the book tracks certain words and idioms through time and considers grammar, vowels and Chaucer in a way that’s a lot more fun than eighth-grade English class. The same process by which we get goofy slang expressions in contemporary America, he has written, follows precisely the script for “how Latin became French.”

McWhorter, a professor of English and comparative literature at Columbia University and the author of numerous books about language, music and black culture, spoke to Salon from his university office. This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

How often does language change in a way that makes people say, “I am really pleased with the way things are going here”? Or “I love this new term I heard on TV or from my young friend”? It always seems to be “The kids don’t know how to speak anyone” or “Can you believe the way people are misusing this familiar phrase?”

Why is our attitude to language inherently conservative even though language itself isn’t?

Well we’re caught in something analogous to the way people before Darwin saw animals in plants. We see these things here, and there is no way to perceive what the past of the Earth is. Or to perceive it you need to be a trained geologist. And no one knows anything about genes yet. So then when somebody comes along and says, “Well actually animals and plants have always been changing. They weren’t like this before, and they won’t be like this later.”

At first that’s counterintuitive and people resist it.

Language is the same way because we have writing. So we think naturally, as people in a literate society, we think of language as what’s on the page. That’s the real thing; speaking is just an approximation. Language sits still. But then we hear new things coming in and unless it strikes us as catchy, we think, It’s not supposed to do that because that’s not what in the book. So when new things happen, they’re processed as vulgar and as broken. We don’t understand that no language could ever sit still.

Right, so we say, “This can’t be right because it didn’t sound this way the last time or five years ago.” Or “That’s not what my dad told me.”

It’s “Because this is what was written down, and what was written down never changes, and language is writing.” So we’re stuck with that illusion.

It’s so hard to perceive this but the way Old English became this English is the same thing that’s happening to this English now. We wouldn’t have wanted those changes not to happen, so why do we want those changes not to happen now?

The evolution that goes back to Anglo-Saxon is just proceeding along; it’s why we don’t talk like they did in “Beowulf.”

Exactly.

So are you just eternally approving about this stuff? Are all the new words and usages OK with you? You spend a lot of time in your book defending the language’s growth and evolution. Aren’t there cases where you just say, “Man, that is just unfortunate.”

No. I approve of all of it because there’s no logical basis for saying the way a language is going is wrong. So it may seem like I’m making a political point or some kind of aesthetic point.

If you thought about me ideologically, you might think that because of some of my renegade views of race that I would be somebody who doesn’t like that language changes. Which is not true. Any linguist, no matter what their politics are, knows that language has to change the way cloud formations have to change. There would be no way for it not to.

But that doesn’t mean that I’m not human. There are things I hear that sound to me a little bit off or a little bit vulgar — especially if they are said by people who are not of what we might call the upper classes. Anybody hears language in that way. But there is nothing I have ever heard that’s new where I have thought, That’s not the way it should be.

And that includes the way people below a certain age use “like.” There is just no scientific grounds for thinking something is wrong partly because if you do a linguistic analysis, anything we use has structure and order and meaning and that includes like. Nothing is just, you know, sprinkled throughout the language with no system.

So, I have my preferences. For example, young people are saying, “Based off of this, blah blah blah.” But to me it’s supposed to be “based on.” “Based off of” to me sounds like someone didn’t quite hammer a nail in. That’s just my aesthetic feeling. My linguistic feeling is that things are changing, and in 100 years more people will probably say “based off of” than “based on.” “Based on” will probably sound a bit Henry James.

And, you know, it doesn’t matter; it’s just the way language changes. Just as in Henry James, you’d say, “in Mulberry Street,” not “on Mulberry Street.” You just know around 1930 there were people saying, “What do you mean, ‘on Mulberry Street?’” We think now, Who cares. And it’s just the same for anything that bothers us now.

If more people could understand that, they’d be less upset about the new things they’re hearing because they’re never gonna stop hearing these new things.

So you’re a guy who’s in favor of any and all slang, and yet your book is not particularly slangy. Can you describe your approach to writing, particularly your decision to write in a kind of sturdy and traditional — perhaps a touch stodgy — but still accessible, style?

Actually most people criticize me for writing in too informal a style.

In the academy, you mean?

Well, from reviewers, too. I actually write these days in a style that combines accessibility with the odd word that I consider kind of cute.

But I write like I talk. And perhaps I speak a bit more formally than most people. But it’s a deliberate choice: I really don’t believe in writing with a tie on, so to speak. Some people do not like that about my writing; they think I am not taking things seriously or trying to pull a kind of stunt. My students often say to me, “I really hear you in your books.”

Part of that is because I am so impatient with conservative ideas about how language is supposed to be. I love old books and the ancient prose. It’s cute like old perfume or looking at a silent movie. But really, you should be able to write more like you talk than we’re often told. So my books are written as if you’re just sitting and listening to me in my living room. And I insist on that with editors, even though a lot of them push back at me.

And yet, you are a scholar of language who approves of slang but who writes with very little of it.

Well, one, I’m not the slangiest person. And two, I know now — I’ve been writing now for 20 years — that if you use something that’s up-to-the-minute, it looks ridiculous in 10 years. And so, for example, in some older books I’d write something like “Don’t go there.” Well now it looks very 1999. So I try not to be slangy but colloquial is what I try for.