On election night a murmur started just as the last gasp faded, “Well at least we can expect some great art.” At first the sentiment was a fatalistic one-off, a brave face, a shy hope that something good would come from the dark days forecast for the Trump presidency. It didn’t take long for the statement to acquire a predictive tone, eventually a waft of desperation was detectable and, ultimately, shrill fiat.

The art of protest is provocative, no question. It’s often brave, usually fierce, sometimes compelling and occasionally inspirational. But is the appeal of the books, films, poetry, painting, television and sculpture produced in response to tyranny, oligarchic pomposity or a fetishistic prioritization of the bottom line universal or simply reactive? How durable is the art birthed from protest? The following essay is the second in a series for Salon exploring the question Do bad times really inspire great art?

On Nov. 6 of this year, just two days before the presidential election, aging American punks Green Day took the stage at the MTV Europe Music Awards to perform their 2004, Bush II-era modern pop-punk staple, “American Idiot.”

Singer Billie Joe Armstrong snarled in the vague direction of then-presidential hopeful, now president-elect Donald J. Trump, asking the audience of largely Dutch citizens possessing close to zero influence on the American political conversation, “Can you hear the sound of hysteria? The subliminal mind-Trump America.”

Apart from the lyrics not making a lot of sense, it also had no effect whatsoever on the outcome of the election. However well-meaning, Armstrong and Co. would have been just as effective by writing “DO NOT VOTE FOR DONALD TRUMP” on a piece of paper, cramming it in a bottle, and chucking it into the ocean, or by whispering “Trump is bad” into a hole.

The clear lesson: punk is dead. And not only that, but it’s been poisoned, drowned, hanged, beaten, stabbed, killed, re-killed and killed again, like some slobbering Rasputin-ish zombie. So when people claim, desperately, that Trump’s America will somehow lead to a resurgence in angry, politically charged guitar music, it’s all I can do to keep my eyes from rolling out of my head.

* * *

To claim that good art — that is: stuff of considerable aesthetic merit, which is maybe even socially advantageous — comes from hard times is the height of delusionally entitled thinking, as if mass deportations and radicalized violence are all in the service of a piece of music. Of course, even the idea of what qualifies as “good times” must be qualified. Given that Trump won the election, it stands to reason that for a majority of Americans (or at least for a majority of electoral college representatives) the prospect of a Trump presidency is a beneficial thing, which will usher in a new epoch of prosperity and big-league American greatness.

There may be truth, or at least the ring of truth, in the idea that objects of artistic value can be produced under the pressure of hardship. While it may be true that an artist like, say, the late Leonard Cohen was able to mine the fathomless quarries of heartache and longing for his music and poetry, it is also true that Cohen was blessed with socio-economic privilege, both in the form of family inheritances and grants from a liberal Canadian government that supported (and continues to support, in various respects) art and artists. His heart may have been hard, but the times weren’t.

At the cultural level, good art tends to emerge from good times. It’s not even about having a well-managed social welfare state (though that, of course, helps). Rather, it seems to be a matter of liberal attitudes reproducing themselves in certain contexts, leading to greater degrees of freedom and greater gains in artistic production and sophistication.

So forget Green Day for a second. Take, as an example, the Weimar Republic of Germany’s interwar period. It was a short-lived heyday of liberalism and representative democracy, flourishing smack between two periods of staunch authoritarianism: bookended by the post-unification German Empire on one side, and Nazi Germany on the other. It was in this context that some of the twentieth century’s most compelling art was created.

* * *

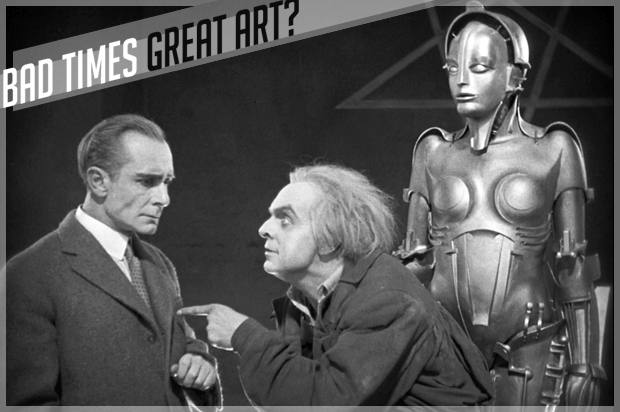

It’s tricky to even think about Weimar Germany without being ensnared by the sickly succour of cliché. You know: leggy chorus girls high-kicking in all-night cabarets, gays and lesbians fraternizing freely, women in short hair lighting cigarettes while the zippy strains of jaunty jazz wafts hither and yon on in a smoky hall — a populace caught in full thrall of freedom. Fritz Lang’s 1922 film “Dr. Mabuse, The Gambler,” the opening titles of which describe it as “A Picture of the Times,” depicts Berlin’s underworld as equally rococo in its bourgeois elegance, and chaotically debased. As the proprietor of an illegal casino puts it, summing up the free-spirited ethos of the era, “Everything that pleases is allowed.”

Emerging from the horror of the First World War, and the 1918 November Revolution that saw the imperial government sacked, the nation’s consciousness was in a state of jumble and disarray. But it was an exciting jumble, full of possibility. The philosopher Ernst Block compared Weimar Germany to Periclean Athens of the fifth century BCE: a time of cultural thriving, sovereign self-governance, and increased social and political equality. Germany became a hub for intellectualism, nurturing physicists like Einstein and the critical theorists of the Frankfurt School. Art indulged experimentalism and the avant-garde, united less by common aesthetic tendencies and more by shared socialist values. It was era of Otto Dix, Bertolt Brecht, the Bauhaus group, Arnold Schoenberg and a new, expressionist tendency in cinema.

Robert Weine’s 1919 film “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari” embodied the spirit of this new age. It told the story of a small community preyed upon by the maniacal carnival barker Dr. Caligari (Werner Krauss), whose newest attraction is a spooky-looking sleepwalker named Cesare (the great German actor Conrad Veidt). By cover of darkness, Caligari controls Cesare, using him to commit a string of violent crimes. With its highly stylized sets, and comments on the brutality of authority, the film presented a whole alternative vision of the world. Both stylistically and thematically, “Caligari” imagined the splintering of the postwar German psyche, presenting a sense that reality itself had been destabilizing, and was reconstituting itself in jagged lines and oblique curlicues. The movie’s lasting influence is inestimable.

In his landmark work of cultural analysis, “From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film,” film critic Siegfried Kracauer described the “collapse of the old hierarchy of values and conventions” in Weimar-era Germany. “For a brief while,” Kracauer writes, “the German mind had a unique opportunity to overcome hereditary habits and reorganize itself completely. It enjoyed freedom of choice, and the air was full of doctrines trying to captivate it, to lure it into a regrouping of inner attitudes.”

Certainly, German cinema of the era often explicitly figures authoritarian characters attempting to seduce the public: from Weine’s madman Dr. Caligari, to Lang’s huckster Dr. Mabuse. For the reforming national consciousness, authority served as a kind of siren song, luring the public out of the rowdy cabarets and nightclubs and back on the straight and narrow. By the early 1930s, attitudes seemed to be shifting. In Fritz Lang’s classic thriller “M,” from 1931, police sniff out a serial killer in part by trying to determine a psychosexual basis for his crimes. It was at once a strike against the unfettered sexual libertinism of the Berlin cabarets, and a sinister intimation of Nazism, which was notoriously marked by its pseudoscientific quackery about the biological basis of criminality and depravity. The hallmarks of Weimar — its authoritarian disenthrallment, its slackening attitudes toward sexual repression, its intoxicating cosmopolitanism — were curdling.

* * *

Weimar poses a number of compelling questions around the subject of historical and cultural Golden Ages. Such rigidly compartmentalized, epochal thinking leads inevitably to collapse. How, after all, can a “Golden Age” be defined without presuming its emergence from, and collapse back into, periods of relative darkness and doom? It recalls Karl Marx’s thinking on historical stages, outlined in volume one of “Capital,” and the idea that each historical period carries within it the seeds of its successor. And it is force, according to Marx, that serves as “the midwife of every old society pregnant with a new one.”

In the case of Weimar, the sense of expanded liberty was undercut in several respects. While the upper and middle classes grew in prosperity, the working poor were afflicted by hyperinflation, and by and large unaffected by new gains made in left-wing modernist painting, cabaret culture and avant-garde cinema. Sexual libertinism bred syphilis outbreaks. Old-stock Germans balked at the moral and aesthetic degeneracy of the new art movements. For such people, Weimar was regarded less like Periclean Athens and more like the ancient African port of Carthage: fit to be sacked, razed, and have its earth salted so that no memory of it could possibly proliferate.

It speaks to a certain historical tendency. To revise Marx, it’s not just that a given society is pregnant with the next one, but that it’s pregnant with resentments and reactions. With Weimar, expanded cultural and political liberalism emerged as a reaction to the authoritarianism of imperial Germany, with the even fiercer authoritarianism and violence of Hitler’s regime emerging as a response to that. Stereotypes of left-leaning artists cavorting in cabarets found their negative image, their doppelgänger, in nationalist thugs roving the streets.

This is not to say that it wasn’t a period of growth and advancement, artistically and otherwise. Rather, it’s a historical reminder that even periods that usher in all manner of artistic and cultural headway need to be relentlessly qualified. It’s not that good times don’t make for good art. It’s that, really, there’s never been such a thing as a distinctly, determinedly, wholly unequivocally “good time.” Even the most shimmering epochs exist in contradiction, conflict and often out-and-out hypocrisy. Like the backdrop of “Caligari,” ours has always been a world of light and shadow. Something to keep in mind as the world stumbles into what’s shaping up to be a new Periclean Golden Age of American Idiocy.