One of my favorite clips from the Jon Stewart era of “The Daily Show” aired on Aug. 23, 2010, in the middle of yet another Fox News meltdown. The crisis at that time was the debate over the proposed mosque near Ground Zero. Fox coverage claimed that the man tapped to lead the mosque, Imam Feisal Abdul Rauf, was being funneled money by an Islamic extremist. And in standard Fox News fashion everyone was in a tizzy over this alleged discovery.

Stewart went on to point out that the same person apparently giving money to the imam, Alwaleed bin Talal, was also the largest shareholder in Rupert Murdoch's News Corporation – a fact that News Corp. subsidiary Fox News seemed to conveniently overlook, especially since they never actually named him in their segments.

That's where the fun begins. Stewart calls in two correspondents, John Oliver and Wyatt Cenac, to help him understand the Fox News coverage. Is Fox News evil or stupid? Did they not know that bin Talal was literally one of their owners? Were they just that stupid, or were they covering it up out of malice? Oliver makes the argument that they are stupid; Cenac that they are evil.

Of course, the answer is that they are both. Watch the full clip here.

I’ve often found myself revisiting that clip now that we are firmly in the Trump era. It can be so difficult to decide whether to laugh at the sheer stupidity of Trump and his kakistocracy or to cry in horror at their pure evil.

That’s when it hit me. We have focused so much on Trump as a reality TV president living in a Fox News-fueled alternate universe that we have missed another key part of his theater: tragicomedy.

Trump’s special brand of spectacle has a long history, and we need to unpack it if we are going to figure out how to challenge what he is doing.

The genre blending of tragicomedy has a rich and complex history, dating well back to the ways that William Shakespeare inserted comic elements in the midst of tragic plays. But the tragicomedy of Trump is a darker, more modern form of performance.

In its modern version tragicomedy isn’t a matter of alternating between comedy and tragedy; it is creating those two reactions at the same time. As Bernard Shaw puts it, it makes “the spectator laugh with one side of his mouth and cry with the other.”

Which is, of course, why all of our faces hurt these days.

The key to the modern form of tragicomedy is the way it destroys the notion of the hero and the villain. There is no redemption, no catharsis, no epiphany, and no moral order — just an endless tension between foreboding and farce. It creates a deep tension in the spectator — a tension that feels impossible to resolve.

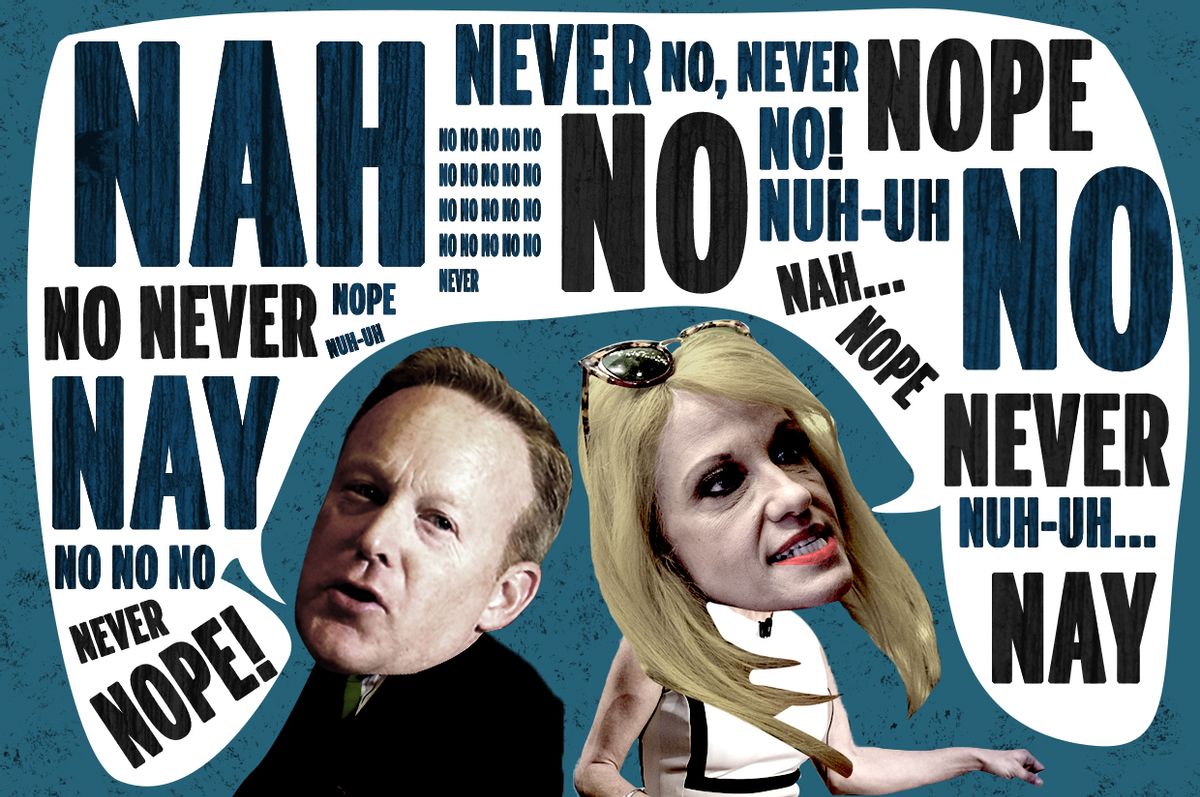

This is why we can have an inaugural address filled with images of carnage and blood, given by a leader who has taped down his tie and allowed his adviser to be dressed like a toy soldier. This is why a press secretary can seem both like Groucho Marx and the frightening voice of Orwellian “Newspeak.” This is why claims of “alt-facts” are both ridiculous and terrifying.

We had to process the idea of golden showers in a Russian hotel at the same time that we pondered the possibility that our election had been hacked.

We also have had to consider the idea that the least educated, least prepared person ever to run for president has outsmarted us all.

The Doomsday clock approaches midnight as the clown car rolls up to Capitol Hill.

It’s dizzying.

We are all so bewildered because we are constantly feeling both amused and shocked. The art of the spectacle of tragicomedy is that it never gives the spectator a break. It produces a never-ending extreme of emotional response and a mind-numbing set of incompatible realities. It wears us out.

Trump, though, has taken the tragicomic form to new levels. One of the special elements of Trumpian tragicomedy is its endless loop. Just as a tragicomic cycle begins to fade out, another pops up in its place. It’s like playing tragicomic Whack-a-Mole. The Stupid and the Evil just keep popping up out of nowhere.

It’s unlikely, however, that the theater of Trump will stay in the realm of tragicomedy.

In the realm of TV, the medium that most informs Trumpland, tragicomedies tend to fail. Eventually televised tragicomic series start swapping out the comedy for more and more tension. The show becomes more of an action thriller with less and less levity. Characters die off or suffer. Tragedy starts to take over. The tension builds, catastrophe looms and the audience is both numb and mesmerized.

We saw this process happen in the George W. Bush presidency, though he had none of the performance savvy of Trump. As Bush became more and more of a mockery, eventually the absurdity gave way to terror, the effects of which we are still enduring.

So what is to be done? Our first step is not to be passive spectators. We can’t let Trump turn our democracy into a game we watch from sidelines. We also have to resist the tendency to be reactive. Politico notes that the editor on the New York Times science desk, Michael Roston, recently tweeted: “President Trump, America’s assignment editor.” Trump is literally controlling the stories that are coming out in the news at a rate that is “unpresidented.”

Perhaps our most important task is not letting our new Drama King decide when we laugh and cry. Modern tragicomedy depends on messing with the spectator, altering her sense of reality, and causing her to question everything. But in this play Trump too is a spectator -- waking up each day and nervously flipping through TV channels and reading tweets. He’s a media junkie, and we can feed him the story.

So whether we use “weaponized satire,” marches of millions, investigative reporting, facts, science, relentless calls to Congress or other forms of active engagement, we must fight to control the narrative. The only way we stop this tragicomedy is by changing the roles of who is in the audience and who is at the center of the story.

Shares