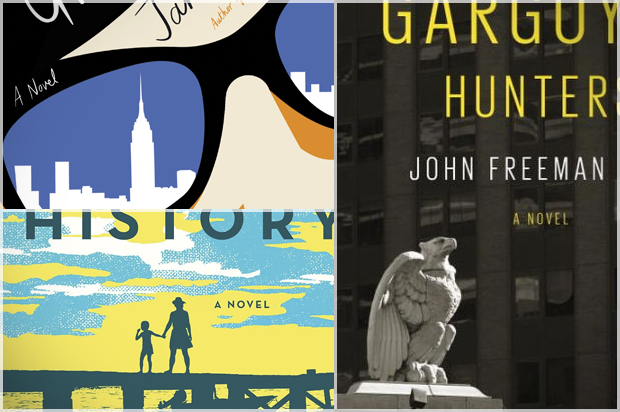

For March, I posed a series of questions — with, as always, a few verbal restrictions — to five authors with new books: John Freeman Gill (“The Gargoyle Hunters”), Jami Attenberg (“All Grown Up”), Melissa Febos (“Abandon Me”), Lauren Grodstein (“Our Short History”) and Joseph Scapellato (“Big Lonesome”).

Without summarizing it in any way, what would you say your book is about?

Febos: Metaphysically? Erotic obsession and abandonment issues. Materially? Hickies and sex and tattoos and books and fathers and ships and the sea.

Gill: Home, obsession, Lost New York, architectural salvage, boyhood, fatherhood, corroded love, the 1970s, art, destruction, creation, self-creation, divorce, young love, an architectural heist, the G-spot, a hurricane, a portrait of the artist as a young gargoyle.

Grodstein: The book is about a mother’s all-encompassing, sometimes frightening, often exhausting and always exhilarating love for her young son.

Scapellato: “Big Lonesome” is about how our big American myths have a way of making us small, unsure, and lonesome.

Attenberg: Remembering everything that happened in your life that made you who you are today, so you can learn from it, get over it, and then move on to whatever’s next.

Without explaining why and without naming other authors or books, can you discuss the various influences on your book?

Attenberg: The view of Manhattan from a window in Brooklyn, the psychotic energy of the streets of New York, road trips through New England, riding the L in Chicago, the 1990s, the 2000s, the 2010s, our most recent election, the work of Jackson Pollock, bodies, skin, lips, genitalia in general, and steak cooked rare.

Grodstein: My influence has been, basically, the experience of raising my kid. He’s a handful, like most kids — but he’s also weird and smart and often very funny. Before I had my son, I expected to love him, of course, but I never expected to love him so desperately. When I talk to more experienced parents, they’re like yeah, duh, of course, that’s what it means to be a parent. But it was still a shock to me — a shock that motivated me to write this book.

Scapellato: Mythology, myths, and folktales; “Golden Age” Wwestern serials; “spaghetti” Westerns; Soledad Canyon in Las Cruces, New Mexico; Las Cruces, New Mexico; New Mexico; western and southwestern highways; snow on a cactus; Houston, Texas; the dude who doesn’t know how to talk about how he feels because he’s been made to believe that dudes don’t know how to talk about how they feel; American history as told by Americans who don’t read American history; chollas, ocotillos, prickly pears; wind in an empty Chicago alley; Western Avenue; the Loop at night, from a distance; brothers; old folks homes; listening; voice; voices; Matka Margie and Schoolteacher Frank.

Febos: Poetry, prayers, feminism, therapy, animals, the bodies of former lovers, and this playlist that I listened to a lot that I call my “Emo Witch Mix.”

Gill: New York City’s elbow-jostling relationship with time. The Woolworth Building. The immigrant stone carvers who came over from Europe in the 19th century and incised their imaginations into New York, turning its streets into a marvelously quirky public art gallery. My mother, who since 1954 has done 125 paintings of Manhattan streets just before they were torn down. My childhood apartment on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, which was crammed with architectural salvage like carved gargoyle keystones, stained-glass windows rescued from Fifth Avenue mansions, and zinc angels that once adorned city tenements.

Without using complete sentences, can you describe what was going on in your life as you wrote this book?

Grodstein: Trying to adopt a baby from China, watching the adoption fall apart.

Gill: Writing about city neighborhoods for The New York Times. Fatherhood with three littles in the house. Suffering a ski accident that broke my back and two ribs and so damaged my clavicle that it resembled an archipelago of bone on the X-ray. Surgery, full recovery, and exultant return to the slopes. Reading all the beautifully written literature I could get my hands on.

Attenberg: A book tour for my last book, buying a house, Mardi Gras, contending with (and then ultimately overcoming) flight anxiety, and watching with horror the beginning of the end of America as we know it.

Scapellato: Moved to Pennsylvania, missed New Mexico. Adjuncted, adjuncted, adjuncted — “part-time” full-time, “full-time” part-time. Got a dog. Moved to Chicago. Moved to Pennsylvania, missed Chicago. Got engaged. Moved to Houston to start a PhD. Left the PhD to move to Pennsylvania to start a one-year full-time teaching job. Moved to Chicago. Got married. Moved to Pennsylvania to start a one-year full-time teaching job, missed Chicago.

Febos: The first half: excoriating fights, lots of crying in my car and on cross-country flights, and very desperate orgasms. The second half: a lot of swimming and kind of serenity that I’d started to suspect was a fantasy.

What are some words you despise that have been used to describe your writing by readers and/or reviewers?

Scapellato: “Despise” is strong! Too strong for me. But a word I’m uneasy with is “absurdist.” For many Americans, I think, “absurdist” signals a work of art that makes no sense for the sake of making no sense. That’s not how “real” absurdism functions, in my understanding of it as an aesthetic mode — it’s just a popular perception of it. The works of fiction that I love the most are the ones where you begin to feel that the exaggeration is not an exaggeration — where what seems absurd is not absurd, because it’s life — where there’s a grounding in the unclassifiably mysterious experience of being alive — where there’s more than enough dark wonder to go around.

Febos: I know not to bite the hands that feed my ego.

Attenberg: Slow, pointless, scattered.

Gill: Sturdy.

Grodstein: Someone said my first book (written from a male POV) was chick lit dressed like a guy (Christ!).

If you could choose a career besides writing (irrespective of schooling requirements and/or talent) what would it be?

Gill: Antarctic icebreaker captain. Door-to-door shaman. Igloo repairman.

Grodstein: Singing in a very classy cabaret.

Febos: Pit-bull rehabilitation ranch runner.

Attenberg: Servant to all things ACLU/Planned Parenthood/Southern Poverty Law Center.

Scapellato: A musician, or a mailman, or a mailman-musician.

What craft elements do you think are your strong suit, and what would you like to be better at?

Scapellato: The sound and rhythm of sentences lead me through every draft, even if I start with an image, an action, or an idea. I work to listen to what sounds alive to me, and then I do what I can to follow it. I try to let the discoveries that I make on the sentence-level ladder up to discoveries that can be made on the character-level, shape-level, theme-level. Language is also what I wish I was better at! More play, more surprise, more modulation.

Grodstein: I think I have a nice way with dialogue. I’d like to be better at knowing when to move a scene along and when to slow it down.

Attenberg: Dialogue, humor, emotional honesty. I’d love to be able to write crazy epic plots. I accept this may not happen.

Febos: I think I have good lyrical rhythm, and I can look at a hard thing for a long time, which might be the most useful skill for a personal essayist or memoirist. I’d like to use less words.

Gill: I’m in love with language and therefore a lifelong wordsmith. Writing sentences and moments and paragraphs is difficult, but I generally have the confidence that if I lock myself in a room long enough I can wrangle words into a form that achieves what I’m aiming for. Story structure is something I have to work much harder at. I begin with characters and scenes and images that feel alive to me and that I sense belong in the same story, and then I have to muscle them into a cohesive narrative form. It’s like trying to give an elegant shape to a sack full of cats.

How do you contend with the hubris of thinking anyone has or should have any interest in what you have to say about anything?

Grodstein: I pretty much assume nobody has any interest whatsoever, and that way, when someone does, it’s a delightful surprise.

Febos: I only say things (in writing) that feel urgent to me.

Gill: Hubris and crippling self-doubt are a two-headed monster with feathers and talons and slavering jaws. I acknowledge that monster as my own and try to stick it in the corner every morning so its two heads can fight it out between them while I’m busy at my computer trying to get some writing done.

Scapellato: I don’t write out of You Should Want to Read What I Write. I write out of Here’s a Thing That I Wrote That Is What It Is and I Hope You Like It But If You Don’t That’s Okay. Don’t get me wrong: I think about the reader when I write. I try to ground what I write in an experience of being alive. I try to use what I write to explore how states of being that our culture tells us are simple are actually complex. I want my work to have meaning, to amount to something — this might be hubris, I admit, or a close cousin to it. But that’s not how it feels. When I’m at my very best, as a person and a writer, the act of writing is an act of hope.

Attenberg: Particularly at this precise moment in history, our words are more important than ever. We must fight to keep our freedom of speech, and then we must respect that freedom by working to reflect the world around us accurately and intelligently and with compassion. It’s not hubris. It’s our job.