Humor masks some painful truths about growing up black in America. While often lamenting the realities of racism, the persistence of white privilege, and the daily battles of existing while black, much of black comedy explores the more personal challenges facing our communities, particularly when it comes to child-rearing. Black comedy also captures how black people cope with the pain inflicted onto us by white America and the pain we inflict on ourselves.

If we really listen to the jokes black comedians have told us about the struggles of parenting, what emerges is a dystopian hellscape where parents resent their children even before they draw their first breath, where children are routinely threatened by their parents in an attempt to get them to “act right” in a white world waiting to crush them. Without most of us realizing it, black comedy provides yet another cultural reminder to black children that because the world is a dangerous and racist place, parents must hurt them to get them ready for it.

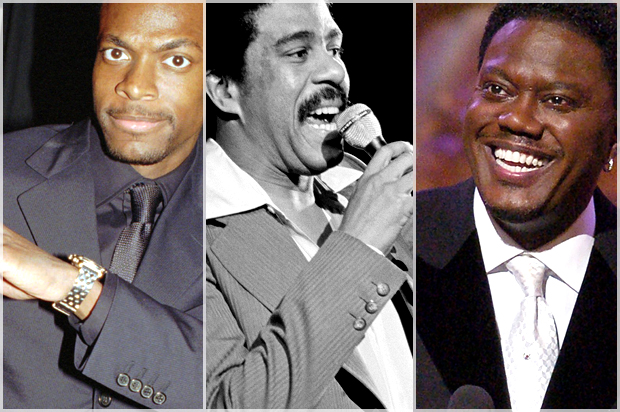

Many stand-up acts are little more than black men confessing their childhood traumas and brutalization of their own children.

Kevin Hart jokes about punching his nine-month-old daughter in the throat for wanting juice.

Bernie Mac declares, “I will fuck a kid up!”

Bruce Bruce advises parents to set the tone for their child’s day: “As soon as your kid wakes up, beat ’em because they’ve done something wrong.”

Reflecting back on his childhood in his 2015 film “Chris Tucker Live,” the comedian said, “My father beat us like slaves.” And then he described how he and his brother were ordered to go into the basement, strip naked, and spread over a couch while their father whupped them with a strap.

The underlying message from these comedians is that, for black children, their very existence is a source of constant irritation to their parents. Requests for food, attention, toys, and information — all normal child behaviors — are met with scorn and violence. Before our children have their innocence destroyed by their first direct experiences with racism, each developmental milestone is met with black parents diminishing them through shame, ridicule, physical force, and even the threat of being taken out of this world by the people who brought them into it.

There is even violence in the nurturing of our children when they are physically injured or sick. Richard Pryor said that after his grandmother whupped him with a switch, she treated his wounds with a cotton ball and peroxide, and then promised to whup him again if he acted up. His audience responded in laughter.

Black comedians also jest about how “soft” today’s children are because they cannot withstand poverty, illness, injuries, or painful beatings from adults. The overarching message is that black children should expect no empathy or kindness in the world, even from their closest relatives.

And yet we laugh at these messages. We find humor in the pain. And we use this entertainment in an effort to persuade ourselves that we turned out just fine. But what’s most disturbing about our laughter is that it demonstrates our inability to recognize that there’s something fundamentally wrong with beating a child until “the white meat shows,” as Bernie Mac famously threatened his nieces and nephews. The audience’s laughter tells us that the whuppings we received have made us numb to our own pain and immune to the continued violence we witness. We have either suppressed our negative childhood experiences or obliterated them from our minds so that we cannot empathize with our children’s pain and vulnerability.

Consider the Peabody Award-winning “The Bernie Mac Show,” an upper-middle-class-black-family sitcom that aired on Fox from 2001 to 2006. Mac plays a loving but gruff and exasperated uncle, whose childless, picture-perfect life with his wife is interrupted when they agree to take custody of his drug-addicted sister’s three children.

The premise of the sitcom was based on Mac’s own life, and he incorporated it into a legendary routine in the very popular stand-up comedy film “The Original Kings of Comedy.”

“I got three fuckin’ new kids in my life,” he gripes to the mostly black audience, which roars with laughter. As he ticks off their ages — two, four, and six — the audience collectively groans.

With a mother who became more and more neglectful as she fell deeper into her addiction, life had been bad for his two nieces and nephew. They were going to end up in foster care if Mac didn’t step in. It wasn’t surprising that they had their own emotional baggage when they arrived at their uncle’s home. Mac describes them as if they are pathological street urchins. The two-year-old, he says, is the bossy, cunning one — a little “heifer” and the ringleader who “works for the devil.” Mac makes fun of the four-year-old’s wide-eyed expression, speech delay, and constant rocking—developmental disabilities caused by her mother smoking crack while pregnant.

“She don’t talk. She don’t say shit. All she do is just look at you,” he says while widening his eyes as the audience cackles. He says he told the child that if a fire breaks out in the house she “better have a whistle or something. . . . I ain’t got time to be lookin’ for no deaf, mute muthafucka!”

Mac then calls the effeminate six-year-old boy a “faggot . . . the first one in the family,” whose sexuality “hurt my heart.” When the boy cries or wets himself, Mac tells him to “act like a man!” When Mac tells the two-year-old, who has snuck into the kitchen to get milk and cookies, that she can’t have any, he says the child looked at him as if she wanted a piece of him, so he squared up in a boxing stance for a fight. The message here is that black children should not ask for food or want for anything, that they should make themselves invisible, and that they are never too young for an adult beating.

Throughout the stand-up act, Mac cusses at the kids and repeatedly calls them “sumamabitch,” “motherfucker,” and “punk-ass.” He admits to the laughing audience that he constantly fought back the urge to call the children other names like, “you ugly son-of-a-bitch” and “you stupid muthafucka you.” Other punch lines also evoke wild laughter from the audience: “Fuck that timeout shit! These kids bad. . . . When a kid gets one years old, I believe you have a right to hit them in the throat or stomach.”

It is difficult for me to laugh at that line, given what I know about child abuse statistics. Children under age one are the most vulnerable victims of abuse, accounting for around 40 percent of all fatalities from abuse and neglect in this country. The majority of children who die from physical abuse are under age two, and studies show that black parents have reported spanking and yelling at children as young as four months, with the frequency increasing as the child gets older. In that same stand-up act, Mac jokes about opening a day-care center where parents can send their “bad-ass kids” to receive three months of free service. There would be no need for secret cameras because he promises to be transparent about his disciplinary practices. He says that if a mother picked up her child who had a knot on his head, and she asked, “What happened to my son?” he would answer, “I took a hammer and slapped the fuck out of him.”

Mac’s language would be cleaned up for his television show, though the violence still resonates. In the opening scene of the pilot episode, Mac looks at the camera and says, “I’m gonna kill one of them kids. Don’t get me wrong, I love them. . . . I know what you’re going to say. ‘Bernie Mac cruel. Bernie Mac beats his kids.’ I don’t care. That’s your opinion.”

Mac’s classic threat to the children is “I’ll bust you in the head till the white meat shows.” That line is akin to another oft-repeated threat from black parents: “I’ll slap the black off you.” His child-rearing tactics eventually get him in trouble when one of the children calls social services. Throughout the show, he defends his disciplinary practices by explaining that he is trying to instill respect in the children.

As one TV reviewer wrote in 2001, The Bernie Mac Show is a “brutal view of how a dysfunctional family might be made to function again. From Bernie Mac’s perspective, that means employing strict rules, verbal abuse and corporal punishment to teach the values of personal responsibility and self-respect. What raises so much of the pain is seeing Bernie Mac attempt to instill these values in children whose young lives have already been damaged, perhaps beyond healing.”

This idea that traumatized children who had rough beginnings can be fixed with a “good butt whupping” also appears in Tyler Perry’s 2002 play “Madea’s Family Reunion,” which was later adapted into a 2006 movie. The no-nonsense Madea, who is played by the cross-dressing Perry, fosters an angry and rebellious runaway whom she whups with a belt even though corporal punishment of foster children is generally prohibited by state agencies.

One of the classic themes in all black parental comedy is to compare “these kids today” with the previous generation. Popular comedian D. L. Hughley, whose adult son has Asperger’s syndrome, quips that “kids these days got diseases I ain’t never even fuckin’ heard of. ‘I’m bipolar.’ That means I have two different personalities.’ We could have never told our mothers any shit like that . . . ‘Mom, I’m bipolar.’ . . . ‘Well both you muthafuckas go in there and clean that goddamn room!'”

For Hughley, good parenting meant a teething child got a face-numbing dose of whiskey on the gums. Mothers chewed and sucked the juice out of pork chops to feed their babies. And a child left alone in a hot car should never set foot outside the car for cooler air, lest they get a whupping for being defiant. Like Mac, Hughley paints a picture of babies who come into the world cursing, and of mentally ill toddlers whose presence is neither desirable nor worthy of celebration. Children are a source of constant need, warranting adult violence from domineering and uncaring black parents.

Another recurring theme in black parental comedy is the denial of feelings to children, especially those who have just been whupped. In one of his routines, Arnez J. turns his microphone into an extension cord and dangles it at a white woman in the audience. Reminding her that she doesn’t know anything about being whupped with an extension cord, Hot Wheels tracks, or Christmas tree lights, he jokes, “Welcome to our world, white people!”

He recalls being hit so hard that his mother knocked the sound out of him. After the whupping, he was sent to his room to calm down, only to be brought back to receive an explanation. Still whimpering and trying to adjust back to normal, he struggles to speak fast enough about what caused the parental wrath. His silence compels intervention as his parent beats him again. The moral of the story is made clear as J. announces, “Ain’t nothin’ wrong with beatin’ your kids. Most of us were beat and we turned out fine.” The audience applauds.

***

Black parents’ threats to beat their children until they can’t grow anymore subconsciously echoes the larger societal attitudes about black children’s inevitable passage into adulthood. Such a message says, “I’m so terrified and feel so inadequate about parenting you through puberty and so I want to attack the part of you that’s growing up.”

In one of his routines, Mike Epps continually riffs on how black mothers deal with their sassy teenage daughters entering puberty. “You know those black mothers love jumpin’ on their daughters. They got that little rival thing.” He makes it plain: if a daughter gets smart with her mother, the mother should smack her and threaten to knock her head between the washer and dryer. “Black mothers love to do that first jump-off,” Epps says.

After the beating, Epps says the mother then calls a friend to shame the daughter—”I had to knock Shaneika’s muthafuckin’ . . . I tried to kick that bitch all behind the damn washer and dryer!” He notes how the mother further shames her daughter by discussing her sexual development with others. “I guess ’cause she got titties she think she runnin’ somethin’ ’round here. I had to let her know, ‘Buy your own tampons! Until you can buy your own tampons, don’t say a muthafuckin’ thang to me.'”

This is yet another example of how children, in this case a daughter who has entered puberty, are perceived as threats to parents. And they must be beaten down for “getting too big for their britches.” What Epps depicts is a scene where a teenager is denied privacy, denied the sanctity of experiencing a healthy progression into womanhood, and shamed for it with a beating and gossip, and for her inability to purchase her own tampons.

In comparing black and white parenting styles, Epps also says that black parents will beat their kids anywhere — “church, the parking lot, court.” Describing a disrespectful white male teenager who cusses at his mother, threatens to kill both parents, and spends his free time in the garage making bombs with no investigation from the parents, he depicts white parents as too permissive. And that has deadly consequences.

“White people, your kids will kill you!” Epps proclaims, adding that white parents don’t beat their children and give them too much unsupervised time alone in their homes. The more responsible black mother has “instincts like she’s in Vietnam.” She will ask questions when her child is spending too much quiet time alone in their room. According to this logic, permissiveness and the lack of beatings leads to white pathology, whether it is backtalk or mass shootings. But whuppings in the black community lead to respect and civility.

Black parents criticize white parents for being “permissive” and latch onto a sense of moral superiority because they would never let their children behave “like those little white children.” The truth is that what spells freedom for white parents and their children is not having a history of racial dehumanization and violence. It is immunity from widespread studies, media images, and stereotypes that demonize black parents and blame them for social ills inside and outside of the black community. It is the ability to live in a society where as a white parent you don’t have to teach your child what to do with their hands when confronted by a cop or how to live in constant racial terror. Black parents work overtime to rein in their children early on, because there is nothing outside the family unit that can protect them from the countless threats and blows of racism.

Watch the different ways that small black children and small white children move through public spaces. The black children are seen by everyone as a nuisance, as unruly, and threatening, and so their parents work to clamp down on their behavior, grooming them to be small, silent, and as close to invisible as possible to avoid attracting trouble. White children are imbued with racial swagger from day one — the sense not only that they belong and have a right to an expansive presence in any environment, but that they are deserving and important and in charge.

It’s easy to see why black comedians are so outspoken about our child-rearing practices. Comedy and, more recently, social media are really the only vehicles that black people have to critique racism and white privilege, and within that, white parenting and child-rearing. After all, white people are constantly demonizing black parenting as the source of violence and other problems in our communities. So we return the favor by insisting that we must beat our children to keep them from growing up to be bombers and mass shooters like white kids, even though there is no evidence that black kids are at risk of committing such crimes.

***

Comedy can also be a source of recognizing; it can spotlight truths and force us to confront our trauma. Unlike the other famous comedians I’ve discussed, Richard Pryor, who in his 1979 Live in Concert film vividly described being whupped by his grandmother, offered insight to a child’s memory of the pain. “My grandmother is the lady who disciplined me, beat my ass. . . . She would say, ‘Richard, go get something so I can beat yo’ ass with it.'”

He described being ordered to get a switch off a tree and snatching the leaves off of it before getting whupped with it. “I see them trees today, I will kill one of them muthafuckers.” He pretended to stop a car, get out, and try to twist and yank the tree out of the ground so that it will never grow up to beat anybody. “You won’t be beating nobody’s ass. . . . That’s some hell of a psychology — to make you go get a switch to beat your own ass with it.” Pryor then chronicled the long, scary walk back into the house, cutting the wind with the switch as he yanked it back and forth in his hand. He listened to its distinctive whistlelike sound. He hoped for snow or that his grandmother would have a heart attack so she couldn’t whup him—and then proceeded to dance around on the stage as if he was getting whupped.

While Pryor’s routine is a source of humor for many, it also forces us to confront our fear, trauma, and pain resulting from whuppings. Though he told the story in a funny way, he didn’t celebrate the whuppings or defend the practice. Instead, he confessed how he wanted to grow up and destroy trees so they won’t bear switches that could be plucked off and used as weapons on other children. He wanted to break the cycle of violence. He didn’t speak from the patriarchal, abusive position of inflicting pain on a smaller person. He actually infantilized himself to show us the unfairness and fear from a child’s perspective. The sights and sounds — his crying and whining and screaming and begging — and his reenactment are so visceral.

While it’s uncommon, Pryor is not the only comedian to use the stage to disrupt the whupping narrative. Former child comedian, Lil’ JJ, now twenty-five, offered a subversive routine at Harlem’s Apollo Theater in which he carried forth Pryor’s truth-telling about being whupped as a child. Like Pryor, he brings the audience to a space in their minds where they can recall what it really felt like to experience the fear of being hit.

As he takes the stage, Lil’ JJ, fourteen at the time, tells the audience, “I want to talk to y’all grown folks.” He proceeds to mock the adults for saying that they’re always talking about how “kids today” are so bad and how much they lie.

“Y’all be lyin’, too,” he says, ticking off examples like the Easter Bunny, Tooth Fairy, Santa, and the Boogie Man.

“Y’all be lyin’ when y’all whuppin’ us.”

While pretending to be a parent spanking a child, he laments the ultimate lie parents tell: that they are whupping the child because they love them. “You not whupping us ‘cuz you love us. You whupping me ‘cuz you mad.” As he pauses to punctuate every word with the simulation of a hit, the audience has little choice but to confront his words and the ways that violence penetrates his body with pain.

What’s brilliant about Lil’ JJ’s routine is that he speaks from a child’s perspective, all while pointing out that parents who whup their kids do so not from a space of love or virtue. He’s able to show that kids are just like adults and they behave the way adults teach them. His message is that children and adults are the same. But when a parent whups a child for committing the very infractions that adults have failed to master, they are actually beating out of their child the negative parts of themselves that they are ashamed of.