“Professor Watkins, you got a sec?” a student asked at the end of class last week as I shuffled ungraded papers into my book bag. “You don’t seem patriotic at all, like not even a little. What’s up with that?”

He was a boy-next-door type of white kid in a vintage Orioles cap and matching jersey. He doesn’t really speak much in class, but his essays are great.

“Why do you say that?” I asked.

“Because of the way you called Jefferson a dehumanizing slaveholder, better known as the godfather of black oppression!” he said with a laugh. “I don’t know. I feel like he did so much more.”

“Oh, he did. But the way you interpret his legacy is a matter of perspective,” I answered. “Recognizing how my ancestors were being treated under his dictatorship doesn’t really make me want to rush out and praise his legacy. Think about it like this: What if you recently found out that player plastered on your shirt was a genius, but also a human-trafficking rapist. Would you proudly wear his jersey?”

“Of course not,” he said. “But I’ll always love my country.”

I thought about his comments on my drive home. History is my first love. Most of my leisure reading involves the topics of slavery and Reconstruction, so I’m constantly thinking about the development of America and the role Africans played. And even after years of research and stacks of books, I’m still amazed at what enslaved and freed Africans accomplished in the world under the harshest of circumstances. By harsh, I mean being kidnapped, stripped of family and culture, having a foreign culture forced on them, and facing overwhelming degradation, beatings, torture, rape and murder in a place where discrimination against black people was not only legal; it was celebrated.

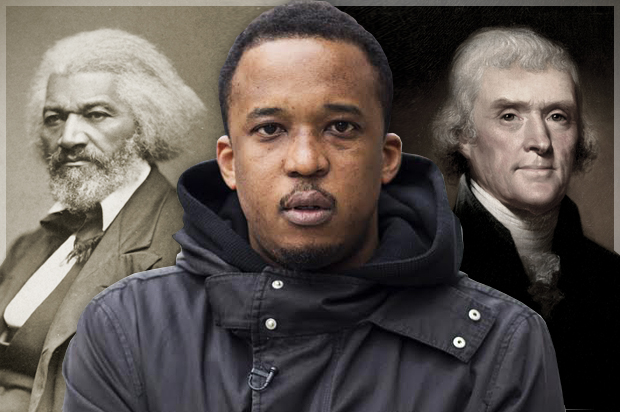

But back to those accomplishments. In addition to the sacrifices made by African-American historical leaders, from Fredrick Douglass to Barack Obama, those accomplishments make me and many other Americans more than proud. And yet the idea of my being both black and a patriot danced around in my mind. It feels impossible. What does that even look like? Does it look like Ben Carson or one of those other black Republicans who can justify anything and everything against blackness? It was Carson who traveled to Ferguson, Missouri, and said, “I think a lot of people understood that [Mike Brown] had done bad things, but his body didn’t have to be disrespected. I heard also that people need to learn how to respect authority.”

“Respect authority.” Is that what being a black patriot is all about? No mention from Carson of the trigger-pulling officer Darren Wilson’s use of the N-word or the racist rhetoric tossed around by the Ferguson police department, only to pop back up in the media calling slaves migrant workers and interns? I don’t think so. I struggle with the idea of black conservatives in general — mainly because they all make comments like Carson’s. Some aren’t as extreme but they still sound like apologetic, subservient, weak cowards. To me, that’s non-American.

And then I think about people like Oprah, Jay Z, Maya Angelou, Dave Chappelle, and all the other black innovators who I don’t know personally but have mentored me from a distance, and how their amazing success stories can take place only in America. Seeing their talents and witnessing their social mobility forces me to work hard in an effort to reach similar heights, and that makes the American Dream a real thing for me.

It connects me to so many others who believe in that dream, making my relationship with the country a love-hate thing. I love the opportunity wrapped around all of those amazing come-up stories, but I hate the bloody history, in addition to the way women, people of color and the LGBTQ community are constantly discriminated against. And yet I acknowledge the progress we’ve made. It’s complicated.

I received an email from my student later on that night requesting a conference to finish our conversation and go over his midterm grade. I set it up for the next day and sent him this passage from Frederick Douglass, published in The North Star:

For two hundred and twenty-eight years has the colored man toiled over the soil of America, under a burning sun and a driver’s lash — plowing, planting, reaping, that white men might roll in ease, their hands unhardened by labor, and their brows unmoistened by the waters of genial toil; and now that the moral sense of mankind is beginning to revolt at this system of foul treachery and cruel wrong, and is demanding its overthrow, the mean and cowardly oppressor is meditating plans to expel the colored man entirely from the country. Shame upon the guilty wretches that dare propose, and all that countenance such a proposition. We live here — have lived here — have a right to live here, and mean to live here.

We both showed up to my office five or so minutes early the next day.

“Professor Watkins, why’d you send that Douglass quote?” he asked.

I unlocked the door and we both walked into my office.

“Look at all of your awards and trophies,” he said, pointing to my wall. “Even you have a great American story!”

“I do,” I responded.

Then I explained what Fredrick Douglass called “the Great Tradition,” a theory that African slaves built this country, meaning that they should not be shipped to a different place after slavery ended and that they deserve to reap the benefits of everything that America has to offer.

“Reaping those benefits have been a rocky road,” I explained. “From slavery to Jim Crow to the prison industrial complex and all the other different types of discrimination that allowed — allow — these racist people and institutions to function.”

The fact is, I feel like the first real American in my family. Yes, my parents and the grandparents I met were born here; however, I’m a part of the first generation in my family to travel, to receive a good education, to own property, to advance. And my good fortune feels tainted when I see so many black people who may never be able to have the same experience. That lack of opportunity, especially among the people who look like me, is what prohibits me and many other blacks from being flag-waving patriots.