“I use my own money and my own work and my own plans, because I like to be totally free. And here now, the federal government is our landlord. They own the land. I can’t do a project that benefits this landlord.”

The Bulgarian-born American artist, Christo, announced in January that he would discontinue his planned “Over the River” art installation. It would have seen silvery fabric suspended over six miles of the Arkansas River in Colorado, an idea that developed in 1985, when he famously wrapped the Pont Neuf bridge in Paris with an ochre fabric. His objection was that the artwork would benefit the “landlord” of the federally-owned river — in principle, the newly elected president would become Christo’s patron and beneficiary of the installation, something the dude could not abide. For an artist this famous to refuse anything to do with the new administration, however remote the link between the decades-long development of an art project that happened to be planned for installation on federal land and the new president, offers a strong, public rejection.

Trump, however, is unlikely to give a crap.

The art world has aimed most of its protests in the direction of Ivanka Trump. This, in itself, is interesting, because it seems clear that Trump himself has his fingers in his ears when it comes to anything related to arts or the humanities, as evidenced by his plan to abolish federal arts funding. Ivanka, on the other hand, is an art fan and seems altogether a more reasonable individual (for what it’s worth, I attended boarding school with her and she was very nice and normal then). Thus a social media movement called “Dear Ivanka” has sprung up, and protesters, among them prominent members of the art community, have picketed not in front of the White House or Trump Tower, but in front of the building where Ivanka and her husband live. In protest, artist Richard Prince returned his $36,000 fee for a portrait of Ivanka he had made, on commission from her family. But Christo’s abandonment of “Over the River” is the highest profile protest, in terms of the money involved and the artist’s stature: He is widely considered an artist of the highest caliber, part of the pantheon of greats who appear in standard Art History 101 textbooks, and a monograph exhibit of his work is closing this week at the National Gallery in D.C.

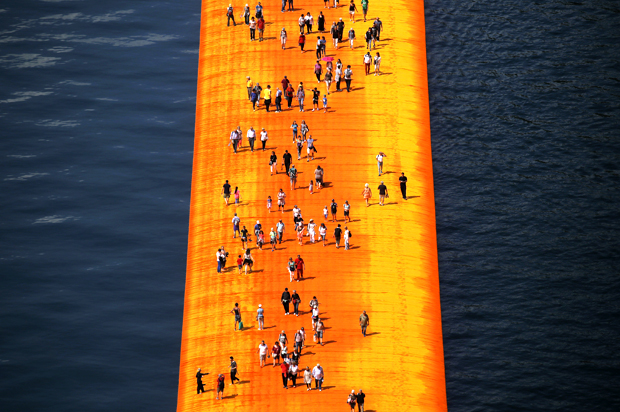

Christo, now 81, is most famous for art installations in which he and his wife and collaborator, Jeanne-Claude (who died in 2009), used immense quantities of fabric to alter the aesthetic of known landmarks or natural settings. In addition to the Pont Neuf, he wrapped the Reichstag in Berlin in 1995, surrounded islands off the coast of Florida with rings of floating pink fabric in 1983, suspended saffron-colored fabric between posts in New York’s Central Park, to create 7503 “gates” through which visitors could walk in 2005 (the planning for which began in 1979), and most recently created “Floating Piers,” a yellow-orange walkway comprised of 220,000 polyethylene cubes floating on Lake Iseo in Lombardy, by which visitors could walk on water.

The idea of an art form that superimposes fabric onto natural or man-made monuments will, of course, find its detractors, who argue that it is silly or an imposition or a waste of time and money. It’s tough to argue with those who just think this sort of thing is silly — that response is sufficiently aggressive that it suggests an entrenched ignorance that reasoned argument will not shift. But Christo has always had a good retort to the money question. He pays for every project himself, entirely out of pocket, financing through the sale of preparatory sketches for projects, and photographs and posters of them. He has never sapped anyone’s wallet but his own. And these projects are colossal in scale, in expense, and in the time required to realize them. He spends years preparing, and millions making them. There’s a fascinating documentary film about the epic legal struggles through which Christo seeks permission to complete his projects, which normally take years to plan, years to approve, and are only installed for a period of weeks. “Over the River” was estimated to have cost Christo $50 million.

I grew up with posters of Christo’s work on my dining room walls. My family has long had an affinity with Christo. My father reviewed “Floating Piers” in the European Review of Books and Culture. And my mother, Diane Joy Charney, a professor at Yale, has a chapter on her relationship with Christo in her forthcoming book, “Letters to Men of Letters.” Trying something a bit unusual this week, I invited my mother to write the coda about Christo for this column.

Take it away, Mom:

I regret that I did not make it to the National Gallery exhibit that ended this week. I’m sure I would have loved it, but I feel fortunate to have my own Christo “gallery” that includes many of the sites featured in the D.C. show. Having recently made a wrenching, downsizing move from my house of 35 years, I was just reassured to see that my prize possession — the enormous, well-wrapped tube of signed Christo posters that were a gift to me from Christo and Jeanne-Claude — is safely ensconced in our new basement, aka “Box City.”

What did I do to deserve such a generous gift? That’s a story in itself. I’m only guessing that the posters were sent in thanks for the poem, “Willing to Take the Wrap: Christo Comes to Tea” that I wrote about Christo and Jeanne-Claude during their 1989 Yale campus visit. That was the beginning of my fascination with them.

I have a habit of writing mostly unsent letters to those who have marked me. Here is one to Christo.

Dear Christo,

This is not my first love letter to you. I’m sure you’re used to getting letters from crackpots, but not necessarily from someone who used to think you were one.

But that’s an older story. At this point, not only do I think you walk on water, but you have already allowed the rest of us to join you. You are always teaching me things. I’m a noseplug type who has trouble taking the plunge to leave my nest. But you know all about life on the edge, and this summer you moved me to set out for your Floating Piers.

I am in awe of your bold, principled decision to abandon the Colorado River project. I heard you mention, after saying how many decades you had been attempting to get permission to wrap the Reischtag, “All my projects have several times ‘no.’ But I am very stubborn man.” And now you are the one saying “no” to your Colorado River-wrapping dream.

Your website features a stunning photograph of you and an equally young Jeanne-Claude atop a rippled sand dune, in search of the site of the Abu Dhabi Mastaba project, on which you have been working since 1977, and that will now receive the full benefit of your passion. A pyramid-sized structure of 410,000 multi-colored stacked oil barrels, it will be the largest sculpture in the world. Thrilling!

I’m thinking about how I could be so attracted to someone who is the opposite of me and many Americans: Your love of the transitory; refusal to hoard; infinite patience in preparing for seemingly impossible, impractical goals; humility and the absence of desire to make a definitive mark on anything. Although detractors like to refer to you and Jeanne-Claude as egotists, you are nothing if not self-effacing. You have made me rethink the way you, unlike me, have never had a problem with investing herculean efforts and decades in a project that might never see the light of day, and that would be subject to a strict time limit. Your projects show understanding of a concept that has always eluded me, and probably many other Baby Boomers: “Game over.” When the preordained time is up, all evidence of an installation must be removed, the site returned to its original state, and all materials recycled.

You modestly say you seek to create only “a gentle disturbance.” You may be the only man for whom those two words are not an oxymoron. In fact, it’s likely that the ephemerality of your fully-realized projects are at the root of their urgency and power. It is rare to hear of anyone who has experienced a Christo project, even a blasé Parisian, who does not confess to having been forever transformed by their participation in it.

I noticed, at The Piers, that my fellow walkers were not necessarily the same people I might encounter at a museum. This is in harmony with your belief that people should have intense and memorable experiences of art outside museums. As I did at The Gates, I could feel the life-changing effect of the project on myself and on those around me.

When asked whether the length of time of an installation could be extended, you said, “It is kind of naiveté and arrogance to think that this thing stays forever, for eternity. It probably takes greater courage to walk away than to stay. All these projects have this strong element of missing, of self-effacement, that they will go away like our childhood, our life.”

Yet, as is the case with Proust’s madeleine (and the posters with which you gifted me), we can hold onto the memory.