Seaweed has earned a bad rap. It smells putrid after baking in the sun. It entangles fishing lines and boat motors. It scares swimmers out of the water by wrapping slimy tentacles around arms and legs. It even jeopardizes major cultural events. Who can forget the large, spinach-like clumps that nearly cost us the aquatic portion of the 2008 summer Olympics? When it’s considered at all, seaweed’s largely considered a nuisance.

And yet, a growing number of coastal states around the country are undertaking large-scale seaweed farming projects. Turns out, these slippery macroalgae may be the unlikely key to sustaining a growing population.

“Seaweed is very important for its natural ecosystem values,” Charles Yarish, PhD, leading seaweed expert and a professor in the department of ecology and evolutionary biology at University of Connecticut, told Salon. “Farming it is a win-win for the environment and the economy.”

So, how is it that these rootless sea tangles are on their way to major cash-crop status?

Marine plants (most of them photosynthetic algae like seaweed) produce around 80 percent of the oxygen we breathe, meaning if they disappeared from the face of the earth tomorrow, our species would struggle to survive. Seaweed also provides a key habitat for marine creatures, and the first link in the aquatic food chain. Without it, the entire system collapses.

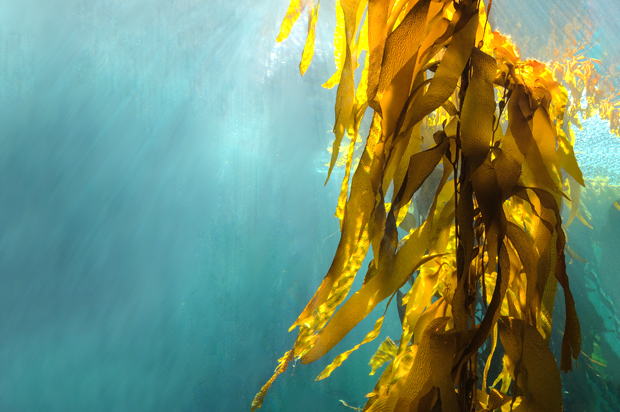

But the slimy stuff is also a nutrient-packed superfood that’s sustainable to grow — it requires no fresh water (an increasingly scarce resource as the planet approaches 11 billion people) and no chemical fertilizers. It also packs a protein- and nutrient-rich punch. Last year, Barton Seaver of Harvard University’s Healthy and Sustainable Food Program told NPR: “Kelp is the new kale. Watch out because it’s coming, and it will be everywhere in the next decade.”

You could argue that seaweed is already everywhere, at least in a subtle way. Mostly grown at thriving farms in Asia, it’s been quietly incorporated into products likely in your pantry and bathroom right now. What’s not being cultivated for food is bought up by other industries. Seaweed extracts are used as textural additives in soups, jams, dressings and ice creams. They’re also a not-so-secret ingredient for brewers, since seaweed makes for a long-lasting, pillowy head on beer. Additionally, from January 2011 through October 2015, 2 percent of body-care products launched globally, including shampoos, lotions and toothpastes, contained seaweed. It may even be the world’s next great biofuel.

Translation: Seaweed is money. The industry was worth $6 billion globally in 2014, and that number is expected to hit $18 billion by 2021.

Considering these myriad benefits, Yarish sat down in 2009 while on sabbatical from UConn to contemplate why seaweed farming hadn’t yet taken hold in America. At the time, the U.S. couldn’t claim a single commercial operation. Today, there are more than 20, with more on the horizon.

“I realized the biggest problem is that everyone was keeping under wraps how to do things, so I decided that I was going to make everything open source,” Yarish told Salon. “This would take the secret out of things by giving everyone a cookbook, a plan to move ahead, and it would spur innovation.”

[jwplayer file=”http://media.www.salon.com/2017/04/552b99c7f300723e2a00eb9942481c90.mp4″ image=”http://media.www.salon.com/2017/04/19f9e1655a1fd95394391f689baddb40_1.jpg”][/jwplayer]

The procedure Yarish and his team established, which was supported by NOAA and the Connecticut Sea Grant program, has been adopted by all startup seaweed farmers in North America. It involves sourcing reproductive tissue from naturally occurring kelp in the fall, when daylight hours and water conditions are right. These reproductive tissues contain millions of cells, which are brought to a lab and made to settle on substrate, aka pieces of thread similar in width to kite string. After five weeks of development, these seed-containing threads are attached to longlines, or 100-yard ropes anchored to the sea or estuary floor. They sit about five to six feet below the surface of the water, depending on light penetration, meaning recreational boats can drive over the top of them. Within five to six months, seeds that entered the water the size of a pinhead are now up to 18 feet in length and ready for harvesting.

They don’t grow passively. As they mature, seaweeds absorb nutrients from the water, including carbon and nitrogen from agricultural runoff or the burning of fossil fuels. In other words, seaweed is a superhero of the sea, tackling two main culprits: global warming and ocean acidification. By sucking up these nutrients, seaweed helps restore the pH level of the water, protecting biodiversity threatened by a changing climate. According to the Guardian, if seaweed farms covered just 9 percent of the world’s oceans, we could counteract all human carbon emissions.

In Washington, a NOAA project is looking at this carbon-mitigating potential. The study, which will last five years, is in its first production year.

“The potential here is significant,” Michael Rust, science advisor for NOAA’s office of aquaculture, told Salon. “How significant is a matter of scale. I think you’re going to see an evolution of products we can’t quite imagine yet. Typically, seaweed is presented as noodles or Nori-type sheets from Asia, but this isn’t really a Western-friendly food item. In the future, you may see, say, a seaweed-based Cheeto. That’s the danger and the challenge and the opportunity — to keep new products in front of the industry as it grows, to get it to a size that will significantly impact carbon in oceans.”

That seaweed could be a secret weapon in the fight against climate change may seem strange, considering climate change is exactly what leads to an overabundance of the stuff (ahem, Beijing Olympics), and these large algal blooms are the very things that suck up too much oxygen and cause oceanic dead zones that threaten the fishing industry. Out of balance, seaweed goes from superhero to villain, fast.

“Not all seaweeds are created equal,” Yarish told Salon. “When there is a problem in the ecosystem, certain opportunistic kinds will start growing uncontrollably.”

But there are enough helpful types existing in all U.S. waters to make for a thriving industry here. Kelp was the seaweed of choice for the industry’s first farmers and, since it’s a cold-water plant, New England is leading the country in number of operations; farms have sprung up in Connecticut, Maine, New Hampshire, Rhode Island and Massachusetts, as well as in New York. The nonprofit GreenWave organization is dedicated to creating a network of kelp farmers in the region in order to build a more habitable ocean ecosystem. Founder Bren Smith offers newcomers two years of training, and he purchases 80 percent of their crops for the first five years at triple the market rate. These crops are then sold to restaurants nationwide. In partnership with UConn, GreenWave has built an industrial nursery in Fairhaven, and a 15,000-square-foot processing center in New Haven.

But other farms are also underway in Alaska, California and Oregon. On the West Coast, red algae like dulse and Turkish Towel are increasingly being employed by farmers. And soon, other types of seaweed could be grown commercially in warmer southern states.

Slowing down industry growth are regulatory hurdles. Without much experience in this type of aquaculture, states are forced to create frameworks from scratch, and potential farmers must gain state approval as well as federal permits. Educating the public, who may be worried about their favorite jet-ski or sailing routes being compromised, can be a formidable challenge. But, according to the experts, it’s only a matter of time before we’re all drinking the kelp Kool-Aid.

“In five years,” Yarish told Salon, “I think it will be turn-key.”