When I recently asked W. Kamau Bell about his second season plans for his CNN series “United Shades of America with W. Kamau Bell,” he replied, “I think that it’s pretty clear what groups in this country aren’t getting a fair shake or aren’t having their stories told by them.”

I blurted out in response, “Is it, though?” In the context of our conversation I was being a little sarcastic, but I meant it to be an honest question. Since November’s presidential election the mainstream media has bent over backward attempting to figure out how Hillary Clinton lost and which constituencies were behind flipping the Electoral College tally in Donald Trump’s favor. The answer has always come back to working-class whites and a resentment toward the focus on social issues by Barack Obama administration.

Throughout the months since the inauguration, media outlets’ coverage of other social movements has waned in favor of examining protests they couldn’t ignore. The Women’s March, the March for Science, the Tax Day rallies and the May Day demonstrations — all were mass actions that flooded streets in cities across the country and provided awe-inspiring images for evening news feeds. Members of the dominant culture might argue that most people in this country aren’t getting a fair shake.

And this overwhelmingly typical viewpoint is precisely what Bell speaks to in the second season of “United Shades,” airing Sundays at 10 p.m.

“During the election when I saw groups that were being targeted, I felt like it became a mandate for ‘Oh we need to talk about them, because America has a narrative around this group that I don’t think is legitimate,’” he said. “It would be clear that I wasn’t paying attention if we weren’t doing an episode about Native American issues through Standing Rock — so we went to Standing Rock. But then it became an easy way to talk about lots of different Native American issues in one place.”

This is what makes “United Shades” relevant, invigorating television. Bell is a comedian who has built a career centered on discussing issues of social and political inequity. He also recently released a memoir titled “The Awkward Thoughts of W. Kamau Bell.”

But he makes these discussions accessible by using humor and curiosity as his tools. In his short-lived FXX series “Totally Biased with W. Kamau Bell,” the host interviewed intellectuals as well as entertainers, training the show’s spotlight on emerging voices as opposed to solely focusing on household names. (Chris Rock was the show’s first guest, but then Rock also was the show’s executive producer.)

“United Shades” enables Bell to take his inquiring spirit on the road to dig to the core of the political subjects that most Americans are content to discuss and evaluate in the abstract. He also uses the fact that he’s not a journalist to his advantage. Even in the face of interview subjects espousing repugnant viewpoints, Bell approaches each conversation with air of openness. In unfamiliar communities, Bell plays the role of the visitor, not the other way around.

In season 1 Bell went into prisons to chat with inmates. He explored Portland, Oregon, to examine the issue of gentrification from all sides. He found out what it means to live “off the grid.” But the most famous episode of “United Shades” was its very first, in which Bell — a tall black man with an Afro — sat down for a long talk with members of the Ku Klux Klan.

[jwplayer file=”http://media.salon.com/2017/05/kamauvid.mp4″ image=”http://media.salon.com/2017/05/kamaupic.jpg”][/jwplayer]

“I’m not a journalist, so it’s about not having a sense of feeling the need to be objective, not feeling like I need to give both sides to an issue, necessarily,” Bell explained. “I don’t have an agenda; I just want to learn. I was very curious about how to wrap a cross. Like how do you do this? I actually was, from a very geeky, nerdy, how-does-this-work level. As much as I could, I was trying to have empathy for the experiences of how a person ends up in this” life, he said.

Because of this, Bell added, “I think there’s a seductive nature to the show. I have sort of an easy approach with tough issues that even if you think you’re not going to like it — if you give it a couple minutes — you may hate me but you might keep watching. It’s clear that I’m not trying to set anybody up for failure. Even if I disagree with them, I want them to get their message out; I want them to be heard.”

Thus in order to piece together an informed conversation about Muslims, Bell heads to the largely Muslim community of Dearborn, Michigan, for a second season episode. Instead of simply running down statistics on white people in poverty, he heads to Appalachia.

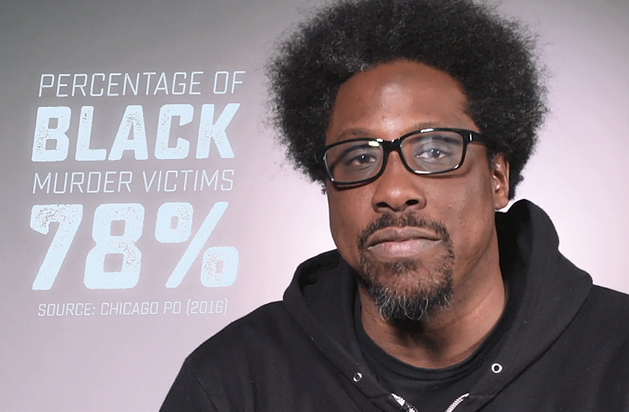

“It’s funny; the first season I got a lot of people on Twitter who would be like, ‘Oh Kamau would go talk to the Klan, but I bet he wouldn’t go to Chicago!’ And I was like, well actually, I graduated from high school in Chicago, so yes I will go to Chicago.” That episode airs on Sunday night, in fact.

Thanks to heavy media coverage on the spike in gun violence and gang activity in that city, Chicago has become synonymous in our national consciousness with lawlessness and urban decay. But in discussing the factors contributing to that skewed perception, Bell also breaks down some of the real causes of the problems. This includes spelling out the city’s history of racial segregation that remains in place to this day, and discussing how cuts to educational funding disproportionately affect predominantly black neighborhoods.

Before all that, however, Bell uses his journey through the Windy City to talk to white people about their perceptions of Black Lives Matter and explain what exactly the movement stands for.

The Chicago episode concretely exemplifies what makes “United Shades” tick effectively and efficiently. An interview with some of the gang members behind the national headlines provides the shiny lure, but before Bell gets to that payoff he leads viewers through other relevant, important conversations about the environmental factors perpetuating the cycle of poverty and violence on the South and West Sides.

In this same way, the season opener mainly explores the question of what immigrants add to this country and concretely defines the difference between a refugee and an immigrant. But that episode also includes an interview with Richard Spencer, the white supremacist poster boy of the alt-right.

And it is this exchange that CNN has used to promote the series’ return. When one recalls that “United Shades” broke through the prime-time clamor by featuring Bell’s conversation with robe-wearing members of the Ku Klux Klan in the first season, using this potentially contentious face-off to attract curious viewers makes sense.

And CNN’s ploy worked. According to Nielsen data, “United Shades” was the top-rated cable news program among adults ages 25 to 54 in its time slot.

Here’s the thing: “United Shades” is not fueled by the showcasing of conflict. Bell never manipulates his subjects into explosive outbursts or upstages them by pounding away at the errors woven into their philosophies. When speaking with Spencer, Bell is friendly, listening and nodding even as Spencer smiles broadly and brays that Western civilization is built on the success of white culture and that immigrants and minorities are a threat.

Yet even in the face of such toxicity, Bell stands firm and asks the questions that need to be asked of people like Spencer.

In this sense he serves as a conversational surrogate, engaging in the difficult exchanges Americans so desperately need to have with others who don’t share their views. Bell wants people to understand the side of the “other” in the hope that we can somehow find common ground — and the acceptance that fulfillment of that hope may never be possible.

“I’m not trying to create a false equivalency between the left and the right, although I am sort of tired of having talks about the left and the right because I think we learned that those ways of labeling us don’t exist anymore. They’re not productive,” Bell said. “But I do feel like if you can just figure out a way to have a real conversation with somebody that’s not poking at them, you can actually get to a different place, where [we can] walk away and go, ‘Huh, I never thought of it from that perspective.’”

Bell continued, “And that’s been my whole approach to my entire life.” He added, “For me it’s the acquisition of knowledge. . . . The show doesn’t exist because of me; the show exists because these people let us go to talk to them.”