“Suddenly there was a bang and the lights flickered”

NEW YORK — A number of us were inside the World Trade Center when the incident happened.

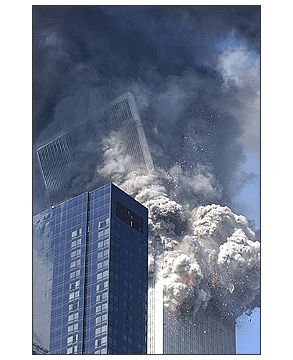

I was attending a National Association of Business Executives conference and suddenly there was a bang and the lights flickered, the ceiling started to shake. I thought that a transformer went out so I just sauntered out of the building. When I hit the door there was a ton of debris on the street and people screaming — lots of smoke.

I ran across the street and looked up and saw the smoke and flames pouring and shooting out of the top; there was lots of debris and dust, office furniture, papers coming out, pouring down like confetti.

I watched in horror as people jumped out of the upper floors to their deaths — desks were coming out — people were screaming for help. It was complete chaos. I called my wife and she said that a plane hit the WTC, so we thought it was an accident. I just sat and watched it burn, there was nothing anyone could do except stay out of the way.

Suddenly out of the sky heading right for us was a huge, what looked like an Airbus. It came into the east side of Tower Two at about a 45 degree angle. There was a huge explosion, rolliing thunder, lots of fire, intense heat and debris flying everywhere. The noise was unbelievable. Ash, smoke and screams are all I remember at that moment.

My feet took over and I joined thousands of people fleeing toward the Hudson River and uptown.

Still have not come to grips with this. I was about a mile away when the second building collapsed. I watched it but could not believe it. How much more? I wondered.

When the Air Force planes started coming over the city, I almost wet myself.

This is truly scary. The worst day of my life — of thousands of lives. I still have not come to grips with it.

— John Dunham

“It just came down around us”

I was on the 86th floor. One World Trade Center. It just came down around me. It just filled with smoke, and the whole ceiling fell down. There were six of us and we went into an office and sat on the floor and watched the smoke increase. So we decided to break a window and we broke four windows with the hammer. We were afraid that one of two things would happen. That the air would rush in, which was fine. Or that it would bring the smoke in, which would increase the smoke. Fortunately, it gave us air, but it also brought in debris, and flying glass and hot stuff.

So we waited, and were picked up, and went 86 floors down and just when I got to the mall, I thought it was fine. And all of a sudden — badoom, another one. And just a windstorm of soot. Concrete. I threw myself to the ground, and everything went right over my head, and everything went black.

The Port Authority people [got me from the 86th floor]. I have to hand it to them, they stuck by their posts. They were there when everything else was crashing. And personnel comforted one another. It was terrific. And then you see the firemen coming up with packs on their backs, 20 or 30 pounds. And theyre going up 86 flights. How would you like to walk up 86 flights? So they did a great job. When the second one hit, it turned black. And of course, half an hour ago another explosion, and the street went black. You have to just bear it out, and keep talking and talking. You couldn’t even see a flashlight.

The other people? I have no idea. We got separated. Someone has my jacket. There were shoes, change, everything. We got separated because we kept changing stairwells. As one got crowded wed move. And it was difficult, because we couldn’t see our way out, covered in soot and ash. Thats why Im going to Bellevue now. I dont know if there was asbestos up there or not. Im glad to be walking away.

–Lou Lesci, New York (as told to Roman Milisic)

“There were people jumping out of the towers”

NEW YORK — I arrived for an appointment at a midtown investment banking office on Avenue of the Americas. Shortly after our meeting began, the receptionist ran in to tell us that a plane had hit the World Trade Center. We ran to the conference room window, which is on the 50th floor, and we had a clear view of the towers and saw a fire burning from the first tower. Moments later, as we watched, the second plane hit the other tower in a fiery ball. It’s terrorism, was our immediate thought. As we watched, shards of glass, like flakes in a Christmas snow ball, began falling from the second tower. It was surreal — there was only one tower left standing. Then as the smoke cleared, within a half-hour, the second one collapsed.

Everyone started thinking about everyone we knew who worked in the building. These were macho banker types, no one was crying, but the mood was very subdued. Everyone knows someone who worked in the towers. I knew people on the 35th floor. I still don’t know if they’re OK. There were people jumping out of the towers as the towers burned.

Shortly after, the head of the investment bank called to say the office would close for the day. I walked down to St. Patrick’s Cathedral and lit a candle. As I left, I came up to a cop on the street and asked, “Is there anything I can do?” He started to break down. He said, “The loss of life is staggering.”

There’s a feeling of Armageddon here. It’s strange, it’s a beautiful day, it rained last night, it’s sunny and bright. But the subways are shut down, and there are no cars or taxis on the streets, just emergency vehicles. Most shops are closed for fear of looting. I just saw a woman running down the street, shouting, “Please give blood, please give blood!” and telling people where to go. It’s the same feeling there was in the Marina district after the San Francisco earthquake.

Air Force jets are flying over every so often. Everyone’s on alert for more violence. It’s an eerie feeling.

— Michael O’Donnell

I stared. Disbelieving. Incredulous

BROOKLYN, New York — I can smell smoke as I type. I can hear sirens.

I am home, in Brooklyn. I am shaking.

I just watched the first World Trade Center tower collapse from the roof of my brownstone. Then I watched the second one collapse on TV.

“That was incredulous, incredulous,” the inane lady on CBS — the one channel that still comes in on our crappy, antenna-reliant TV — as Tower 2 crumpled and fell in on itself.

And the wrong word sounded right.

Incredulous is just how I felt as Tower No. 1 disappeared in a huge poof of smoke. I thought maybe it was some kind of optical illusion. It simply didn’t seem possible.

Until about a half-hour ago, we had a perfect view of the Twin Towers from the roof of our four-story Park Slope brownstone. We couldn’t see much else of Manhattan, but the two tall buildings reached up like two long arms, as if offering formal greetings from across the river. And while the business, commerce and bustle of downtown seemed so far from our quiet, historic street, they made it clear the action was really right next door.

So after I glimpsed live feed on TV — and after I’d ascertained that my fiancé had made it safely through downtown and to his midtown office — I threw on some shorts and climbed the fire ladder to our tarry roof.

I opened the hatch to a perfect, sunny fall day. The squawking of the TV and hysterical e-mail exchanges of the morning seemed far away. The explosion I’d heard at about 9 a.m. — like distant thunder — seemed completely unreal. None of it seemed possible.

I waved at a neighbor watching from his roof across the street, but he didn’t see me; his eyes were trained in a different direction. I saw a batch of workmen on the skeleton of a building going up a few blocks away, gathered into a precarious clump, watching too.

I turned and looked.

The towers were smoking all right, black filtering off to gray, then white. One of them had a red glow that I took to be flames. They looked wounded, but not mortally. There was that strange feeling of disconnect and reconnect that you get when you realize that what you’ve seen on TV is real.

“Wow,” I said, to no one in particular. I needed to hear my own voice.

Afraid to venture too far on the borderless, slanty roof on my own, I perched right at the opening to the hatch and watched, trying to make sense of it. Trying to comprehend it.

It’s going to be strange, I thought, seeing the buildings with these new gashes when the smoke clears, flashing forward to the rebuilding phase. Imagining scaffolding on the building’s damaged skin.

My footing seemed a little insecure beneath me. I had a flash of falling, felt frightened. Thought of the people in the building.

Made myself think of them.

People were in there. How many? Maybe people I knew. Certainly people who people I knew knew.

They must have all gotten out, I thought, thinking too of the awful images from the last World Trade Center bombing. People trapped in elevators, collapsing on stairwells, trying to save their colleagues.

They must have learned from that, I think. And it was early in the morning. Who gets to work at 9 a.m.? Only a few people, and they all got out, I thought. I didn’t even let myself think of the people on the airplanes.

Swathed in the depths of my denial, I continued to watch as smoke poured out and grayed the perfect blue sky. Wind rustled in the trees and lifted my hair. I couldn’t help myself from feeling a little bit … peaceful.

I contemplated the hubris of building a building so tall, then felt guilty for the thought.

After a few more minutes, I grew bored. I decided to go inside. But as I took my last mental snapshot of the building, the tower that looked the most calm — the one gasping less smoke, the one without the fire, the one that looked like no big deal — appeared to tip forward and fall.

“Oh my god,” I heard myself say, loudly, looking around at the empty neighboring roofs for verification.

I said it again, “Oh … my … god.”

Then I felt foolish. I must have made it up. It simply wasn’t possible. It couldn’t be.

All I could see was smoke, white this time. The top of the building must simply be obscured, I thought. It couldn’t be gone.

It couldn’t be gone.

It couldn’t be.

But yes, it looked like blue sky peeking through beyond the billows of smoke.

I stared. Disbelieving. Incredulous.

More clear blue sky.

And then the enormity of it hit home. All those people.

“Suddenly, everybody was a potential terrorist”

WASHINGTON — I rode my bike down to the White House shortly after the attack on the Pentagon. I made it as far as the intersection of 16th and H Streets, where thousands of people were gathering in the streets and on the sidewalks. People were looking up at the sky, watching for another airplane attack. “Here comes one!” someone would say. I felt my heart pounding in my chest. People with machine guns stood guard on the roof of the White House. They didn’t fire at the aircraft; it was a U.S. fighter plane.

Rumors were rampant that there were other hijacked planes in the air heading for Washington. Police and Secret Service agents were trying to push people back, but it was too chaotic. Then a huge explosion erupted; I couldn’t tell where it came from. Was it the White House? Another explosion at the Pentagon? A car bomb? For the first time since I’ve lived in Washington, I was afraid for my personal safety. I rode up Pennsylvania Avenue, past the FBI building. Was that a target, too? I found myself looking up at the sky, watching for planes careening toward the building.

I made my way toward the Jefferson Memorial, where I saw the black smoke billowing from the Pentagon from across the Tidal Basin. The police were closing all the roads, but I managed to get on the 14th Street Bridge. Military brass were walking across the bridge away from the burning building; many looked stunned and confused. I stopped in the middle of the bridge and watched as fighter planes and helicopters buzzed low over the Potomac. Was President Bush arriving? Was it now safe, or were more attacks imminent?

Along Constitution Avenue, I joined a crowd that had gathered around a person with a radio. There was a report of a car bomb at the State Department. I was only a few blocks away; didn’t see any smoke. But sirens were screaming all around. I made my way to 23rd Street. There were a lot of police around the State Department, but no evidence of a car bomb. But what about that van? That guy with the briefcase? Suddenly everybody was a potential terrorist.

— Brian Hansen

Like the worst sort of TV movie

NEW YORK — I am writing a review for the Nation of the Bill Ayers memoir of the bomb-happy “Days of Rage” Weathermen and I am feeling ironic about all the sirens on the streets outside, like Muzak, and then we leave the house to vote in the New York primary and while there is a strange absence of electioneers on the upper east side of Manhattan, nobody at the junior high school polling place says anything about the World Trade Center or the Pentagon, so my wife decides on this beautiful day to walk across town and maybe shop for something, and I go back to my computer, where I try and can’t get online to check for e-mail, so I just stroke some more ’60s violence, until the phone rings and my stepdaughter downtown tells me that maybe I should be watching television because it is like the worst sort of TV movie, and I don’t know what she’s talking about, and I’m just in time to see the reruns of the collapse of the towers, and the talking heads are full of just as much blank incredulity as I am, after which the local news is all evacuations and no subways or buses to evacuate on, and go south from Battery Park and ferry boats will get you away to safety, plus gas line explosions are suggesting the possibility of methane clouds, plus the primary in which I have already voted has now been officially canceled, and what happened to all those passengers on all those hijacked airplanes, and I can’t reach my daughter in Washington, and then my son calls from Salon because journalism marches on as if sense can be made of this story through sheer speed and frantic hand-waving, and so now I will try to fax this to San Francisco and then go back to being wired to the gills and stupider than ever.

— John Leonard

Eerie, bizarre calm

WASHINGTON — I rolled out of my bed at the customary time this morning to the site of fireballs crashing out of the World Trade Center, then still in their intact state. I contacted a few friends and slowly began to realize and was told what should have been obvious: that two separate jumbo jets don’t crash into the World Center through some sort of logistical snafu. As the sleep began to clear from my brain the first reports came through of a similar attack on the Pentagon and other attacks near me in Washington, D.C., attacks which thankfully proved untrue.

Stunned and verging on panic, I hesitated to leave my apartment and put myself out of touch even for a moment with the terrifying onrush of events, some of them occurring very nearby.

Eventually, I walked out into my neighborhood to a scene that I can only describe as eerie, bizarre calm. The coffee shops near my apartment were closed with surprisingly quickly constructed signs informing patrons that they were closed because of the World Trade Center catastrophe. Another Starbucks nearby was busily locked and bolted as I approached.

Washington was beautiful this morning. And if you didn’t know what was transpiring, you would have sensed little panic and little apprehension. The only sign of what had happened was a steady tide of men and women in business suits streaming up Connecticut Avenue, in the opposite direction I was walking, obviously making their way by foot from the numerous buildings 10 and more blocks away that were being evacuated in expectation of further disaster.

Yet none of the faces bore signs of panic. Perhaps vaguely stunned and just walking, would be the best description. Very few people were talking to each other, most were just cradling their cellphones trying to get through to nearby friends and anxious, distant relatives.

People were calmly shopping in the neighborhood market. A few were buying jugs of water, something that hadn’t occurred to me. So I did the same. For all this, though, some family was moving into a new apartment, carting boxes, unfazed, maybe unaware, of what was happening around them, the fear or shock bubbling up through others around them. Another man was washing the windows on the front door of my apartment.

— Joshua Micah Marshall

I hear something: Boom. It can’t be

NEW YORK — It began the way all disasters seem to when you’re not in the middle of them, with a minor aggravation. At 8:45 a.m., my Greenwich Village apartment rumbles as I’m getting dressed; a low flying plane. “Must be some kind of military exercise,” I grouse, and then pause, realizing that since I moved from San Francisco three years ago I’ve never once had my windows rattled by flyboys. Weird.

“This just in: There’s been some kind of explosion in the top floors of the World Trade Center,” said the WNYC announcer. I contemplate heading out to the street for a look. You can see both towers perfectly from 6th Ave. and West 12th St.. But I probably wouldn’t even be able to see the smoke. “We’ve got unconfirmed reports that a plane hit the north tower,” he says a minute later, and I’m out the door.

A big, smoking wound gapes on the side of the north tower. Clumps of people stand in the street. A guy in a baseball cap tells me he saw the plane. “It was a passenger airliner,” he says. “It was flying really low, and swerving. I didn’t see it hit, but I heard it.” Tiny shards of fire flicker in the hole.

I rush upstairs to listen for updates. This has to be the worst aviation accident of all time, I think. I’m pouring coffee and I hear something: boom. It can’t be. “Another plane just hit the other tower,” a frantic man with an Indian accent tells a radio reporter. No, that can’t be right. The crash must have set off an explosion in some part of the tower. “A second plane has hit the south tower,” says Highland.

I’m on the street again by the time I grasp that this is no accident. Huge billows of smoke cover the tops of both towers. Honking cars covered with gray dust crawl up 6th Avenue through the huge crowds of people staring south. I go back and forth between the street and my CNN-filled apartment a half dozen times. I’m heading around the corner when I hear people scream. The south tower is down. I see the north tower fall on live TV, and by the time I get to the street people are stumbling around on the sidewalk weeping, and a man is shouting that everyone should head to the hospital on the corner. “They need blood!”

There’s a big empty patch of sky on the horizon where I used to admire the towers tinted pink by the dawn. Gone. More people than I can count, or can even stand to think about, now have even bigger holes in their lives.

“There’s a big white plane headed this way!”

WASHINGTON — A controlled chaos erupted in downtown Washington in the wake of an explosion at the Pentagon, directly across the Potomac River. Streets were clogged with commuters battling bumper to bumper traffic as federal office buildings closed for the day and Washingtonians attempted to return to their homes. As White House personnel were evacuated, law enforcement authorities enlarged the security buffer around 1600 Pennsylvania Ave.

Within two blocks of the White House on 17th Street, one police officer hurriedly waved pedestrians west, apparently concerned about imminent danger.

“West, west!” the policeman yelled. “There’s a big white plane headed this way!”

While some D.C. residents rushed down the streets crying, panic painted on their faces, most seemed gravely curious. Small clusters gathered on street corners, exchanging information. Cars stuck in traffic with news radio blasting attracted interested pedestrians.

Sirens wailed continuously as police cars and ambulances attempted to maneuver through the clogged downtown avenues. Commuters cursed their cellphones, many of which had difficulty getting signals. At downtown pay phones, lines formed of individuals wanting to call family members and friends.

An earlier report of an explosion on the Mall — the multiblock field between the Capitol and the Lincoln Memorial — turned out to have been inaccurate. The smoke that appeared to have been coming from the Mall, if one was north of downtown, actually emanated from the Pentagon, where the explosion was reportedly severe. A 60-foot section of the United States’ military headquarters was ignited in a horrific conflagration and then collapsed. Downtown hospital emergency rooms began admitting casualties from the Pentagon explosion.

“There is nothing”

NEW YORK — As I left my polling place, amused and disgusted at the old Italian ladies running the place and shouting abuse at the old Chinese people trying to vote, I saw smoke billowing between the buildings another two blocks away and I could see it was streaming out of both of the twin towers. A crowd had gathered near Canal Street and we could see flames shooting out the sides and a gaping round hole in the north tower.

As always in these moments it didn’t register as real; the crowd was giddy, the people who spoke English passing on what they heard, the people who spoke Chinese doing the same. Someone said it had been two planes that crashed 15 or 20 minutes apart and that was incomprehensible. My mind couldn’t even formulate the word “terrorism.” I took a few pictures and then resumed my walk to work: My office is 10 blocks from the World Trade Center and it still hadn’t sunk in that this wasn’t a normal business day anymore. I planned to be witty later and say my first thought was that there had been a coup, Giuliani had declared martial law and canceled the elections.

After I crossed Canal Street I remembered the photograph on my wall, taken from my roof during the Los Angeles riots in 1992, of the smoke billowing up from Hollywood Boulevard and the palm trees and the American flag in the foreground. I turned around and went home, climbed to my roof in little Italy and took more pictures — my apartment has the coveted southern exposure and a clear view to downtown less than a mile away. I went inside to listen to the news, first on the radio where I couldn’t find NPR (I have to assume they broadcast from the WTC antennas) and then from the television. When I lived in L.A. I first saw the smoke, just six blocks from my house, on the television screen; when the first WTC tower collapsed, again, I was looking at my TV instead of out the window, trying to find out what was happening, how many planes had been hijacked and what Pittsburgh could possibly have to do with any of this.

Enough with the mediated experience. I went back to my roof to watch the second tower’s flames spread and peer at the glimpses of emptiness through the dark smoke where the first tower used to be. By now I could see crowds filling the streets and sidewalks, walking away from downtown, in mass exodus up Lafeyette Street and then three things happened simultaneously. I saw the second tower go, my ex-boyfriend called from overseas and all the loss sank in. At first you feel swept up, everything is suddenly so present tense, I remember that same feeling in L.A. crossing the street and knowing all bets were off — I’d gotten a $60 jaywalking ticket the month before and I knew no cop was going to ticket me then. Now suddenly, I had a sharp hollow feeling in my chest; I watched the giant antenna on top of the tower list to one side, then the whole building sink from view, replaced by another massive balloon of smoke.

It was just past 9 when the planes hit: Everyone was at work, there was no way they could have evacuated the towers. The people in the planes. The people on the ground. I curl up in bed and close my eyes while the television tells me about Camp David and the State Department and the other hijacked planes. Soon we’ll have to deal with the ugliness to come, the Bush posturing, the anti-Arab hysteria, the retaliatory strikes, the comparisons to Pearl Harbor and the rest of the opportunistic politics. Right now I’m going over to St. Vincent’s Hospital to give blood. The wind has kept the smoke blowing to the east, so the skies in every other direction have remained the clearest, most intense fall blue. Its a beautiful day. Where I look out my window every day, where the World Trade Center used to be, there is nothing.

— Jen Nessel