After three seasons, HBO's “The Leftovers” ends tonight, and I keep returning to this: I’m glad all those people vanished. Salman Rushdie, Shaquille O’Neal, the pope, Gary Busey, Norah Durst’s family, the other 1.99999 percent of the world — I wouldn’t bring a single one of them back if I could. And nothing that happens tonight will change that.

Truly, “The Leftovers” has pulled off an immaculate feat. A show about a departure, created by a man behind one of the most infamous finales in television history, made in an era when prestige television finales receive more scrutiny than a president’s cabinet nominees, ends tonight. Its last act won’t sway my final judgement of it. I feel at peace before hearing its last words.

Why?

Well, foremost because there are no polar bears, special children and time-travel theories here. The remaining mysteries on “The Leftovers” are existential ones, not cliffhangers.

The show has yet to provide an answer for its central question — what happened to 2 percent of the world’s population on Oct. 14, 2011? — and it probably won’t ever. That’s just fine. It shouldn’t. The question was always meant to be rhetorical, something for the characters on the show to grapple with rather than for the audience.

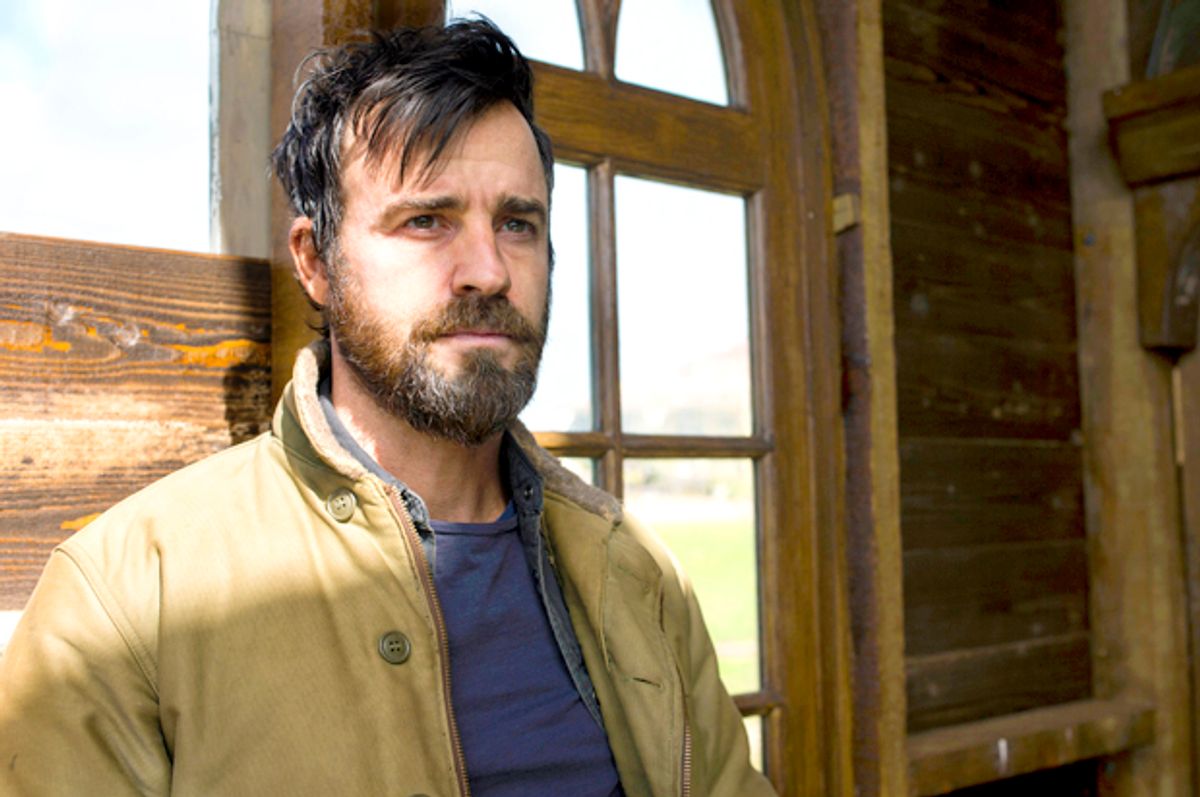

Damon Lindelof, the showrunner for “The Leftovers,” already reckoned with the fates of the departed; that’s what “Lost” was. With “The Leftovers,” he flipped the script, telling the story of the people left behind. The show was never as interested in what happened to the departed — or, for that matter, whether there is a god or whether that god might be a steely-eyed small-town police chief — so much as using those questions to explore how people cope with grief and mystery.

A quote from the Nobel Prize-winning theoretical physicist Richard Feynman comes to mind:

I think it's much more interesting to live not knowing than to have answers which might be wrong. I have approximate answers and possible beliefs and different degrees of uncertainty about different things, but I am not absolutely sure of anything and there are many things I don't know anything about, such as whether it means anything to ask why we're here. I don't have to know an answer. I don't feel frightened not knowing things, by being lost in a mysterious universe without any purpose, which is the way it really is as far as I can tell.

“The Leftovers” has been great — specifically in its last two seasons — because it has managed to thread a tricky needle. It embraced the beauty of the unknown while deriving drama from its characters’ mad search for truth and meaning.

We’ve seen characters leave their families for silent cults, forge dysfunctional families, seek out holy huggers and holy cities, pseudoscience and masochism. But each coping mechanism has proven to be just that. There’s no escape from pain, and searching for a magical salve is a futile search. But light, levity and love abound.

It took a season for “The Leftovers” to internalize that “but.” Next to the show’s first season will forever be an asterisk that reads “Unbearably Bleak.” Upstate New York provided a gray pallor. Half of the cast didn’t speak. No one laughed. We were forced to witness tear-filled teenage erotic asphyxiation, the hunting of runaway dogs and a stoning. Soundtracking it all was James Blake’s morose crooning.

Lindelof has attributed the first season’s unceasing solemnity to his being “in a dark place” when he was writing it. He was attempting to translate the tragic sadness which he found beautiful in Tom Perrotta’s book to the screen. It didn’t work. The beauty was lost in the darkness.

But that “The Leftovers” so drastically improved in its second and third seasons will inform its legacy more so than the first one's shortcomings.

The second season began with Lindelof and his writer’s room trolling one of the show’s fiercest critics with a long biblical scene that had scant bearing on the show’s central plot. Love or hate the sequence, it pointed to a new willingness for the show to go down paths for no other reason than, you know, why the fuck not? Could death be a hotel in to which you go to assassinate your demons? Why the fuck not? Could a middle-aged white woman get a Wu-Tang tattoo and then jump on a trampoline to the tune of “Protect Ya Neck”? Why the fuck not?

In its second and third seasons, the core of “The Leftovers” remained tragic, but the show got delightfully weird and, more importantly, fun. The shift in music choices says it all. Rather than hitting death on the nose with James Blake, the show began bouncing around to the Wu-Tang Clan and gracefully detonating bombs to vintage French tunes. The aftermath of tragedy was allowed to be multidimensional — full of agonizing pain and joie de vivre.

The show’s transformation is a testament to creators’ capacity to look at what they’ve made critically and revamp it. Television is a medium that allows for that sort of evolution. Because television is ongoing, it, unlike movies, which are contained, is impervious to perfection.

And that's the other reason why tonight’s finale cannot taint “The Leftovers.” From the jump the show was imperfect. If in its last breath it sputters or stumbles, so what? That happens when you’re feeling around in the dark.

Shares