Queer culture. Is it endangered? Gasping its last? Just sad? Consider the following.

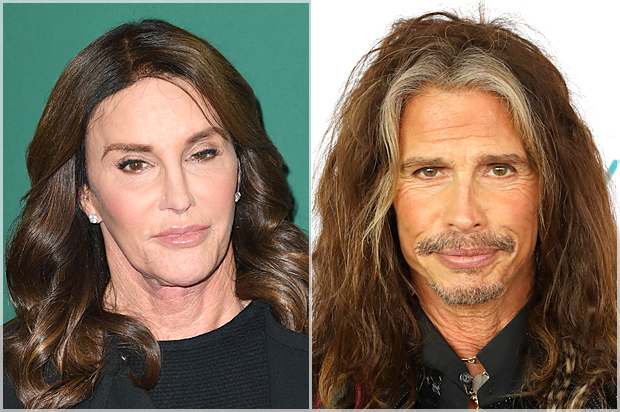

Caitlyn Jenner, captioning a picture of herself posing with Steven Tyler, jokingly says that they are working on a duet of “Dude Looks Like a Lady”; apparently it was once her theme song, and she loves it. Huffington Post’s Queer Voices Deputy Editor James Michael Nichols critiques Jenner’s “almost too predictably problematic” use of this “dangerous” trope, as connected to a history of violence perpetrated by those who don’t consider trans women real women.

Students returning from an undergraduate queer studies conference tell me that they were deeply disturbed by a drag queen’s performance there because she made comments that were insensitive and triggering. I argue that it is the privilege of drag queens to ridicule, insult, and generally slay in all ways absolutely everyone in the name of humor — and that this privilege constitutes a moment of public power for a marginalized group. I say that there is empowerment in humor and in being able to take what the drag queen dishes out. They do not accept this explanation, failing to imagine how pointed insults could be acceptable in what is supposed to be a supportive community.

A non-binary student critiques a faculty colleague of mine in class for using the term “drag queens” to describe the self-identified drag queens who resisted at Stonewall. My colleague, who is 35, queer, and teaching Sociology of Sexuality, is informed that this is an incorrect and insulting term.

What do these examples have in common? What has become of us queers — and of our culture? Whose culture, you might ask? Well, mine. I am a white 49-year-old femme college professor whose sexual interest is butch lesbians and trans men. Yes — sexual. Not as in “partner,” like starting up a small business together. As in sex, as in “lover,” which is what we called our lovers before it all became so sanitized and proper. I came up in the ’80s and ’90s, when queer culture was hot because it was outsider culture, and I liked it that way. Queer culture, heavily dominated by gay men, particularly white men, and their concerns and aesthetics, from Tom of Finland to Judy Garland, was flawed, frustrating, even infuriating at times, and beautiful to me despite the marginalization of lesbians and trans people within it. It had glamour. It had glitter and leather and sex and history and laughter.

I liked the centrality of playfulness within this culture — the fact that we couldn’t take ourselves too seriously because, as with many marginalized groups, humor was survival. This was the era of ACT UP, of Silence = Death — an era of many specters, from AIDS to rampant alcoholism and drug addiction in our community to poverty, particularly for gender non-conforming people, queers of color, and lesbians. It was an era of suicides and murders, just like today. It was a time of no legal protection, of the demonization of bisexuals, of the invisibility of trans and genderqueer people, of lovers who were also called “friends” or “roommates” in dangerous circumstances. It was all these things — serious and terrible and terrifying — and yet it was also a time of joy, pleasure and celebration — a frisky, sensuous era of Pride symbols, drag balls, Dykes on Bikes, public sex. It was underground, and it was a risk in any case. It was a time for queens of all sorts in their outrageous, edge-pushing fabulousness. I believe that its special kinds of ecstasy were in fact intimately connected to its special kinds of marginalization, as forms of resistance. And if you didn’t have a wit, a sense of humor, then you didn’t get it. You just didn’t.

Queer culture today: Marriage wars. Custody wars. Bathroom wars. Assimilation. Rights. Sigh.

We deserve all the rights, obviously. We deserve to be who we are and who we want to be and not to be harassed or killed for it, and we deserve to have and keep our children and set up shop in the suburbs if we want. We deserve to pee in peace in the bathroom that suits our identity and serve in the military. Obviously. I myself have lived in fear as a parent with no legal rights. But. Apparently, in the pursuit of rights and respectability, we have somehow shifted as a culture from the celebration of eros to the celebration of victimhood — to comfortably inhabiting a state of being prickly and appalled — and apparently we now have to be and feel like victims in order even to deserve rights. This worries me.

Are we going to become so focused on our legal standing and our feelings, so invested in queer culture as a culture of rights, respectability and sensitivity, that we lose our playfulness and the toughness that used to define survival? Do we just not want to be tough anymore? Are we too emotionally exhausted, or just too bourgeois, to appreciate a classic bitchy drag emcee? Her sensibility was always at the cultural fringe — is there no room for it now? Or are we the truly bitchy ones, ever ready with the political upper hand raised to slap down those among us who still want to play around the edges, where things are a little less comfortable and correct?

“Dude Looks Like a Lady” is crude and transphobic and promotes straight sex tourism. It is also a song about a normative male protagonist’s being irresistibly attracted to a trans woman who “had the body of a Venus,” and having sex with her and enjoying it. It is complicated and contradictory. As a concept, the phrase “dude looks like a lady” is in fact in the neighborhood of classic drag, especially drag in the ’80s and prior, before “realness” became achievable or even desirable. Because the beauty of drag is illusion, a moment of lighting, smoke and mirrors — wigs, makeup, layers of hosiery, and what is underneath all of that — not seamlessness, not a lining up of all the facets of selfhood but rather a disruption of fixed categories as attached to the body. Looks like — if it’s not that, then it’s not drag. This is far afield from many of today’s queer identities, which hold up as their mirrors Truth or the Actual, though it is very true in what it challenges regarding bodies, genders and natures.

Steven Tyler’s song is ridiculous and dangerous indeed. It does not promote understanding of the complexity of queer identities but reduces genders to opposite and incommensurate extremes. But it is also interesting that Caitlyn Jenner loves it, because the word “dude” is not a measure of biology, of essence, but of masculinity, and maybe Caitlyn Jenner, formerly a major dude, has a right to play with masculinity and illusion. And what if this is how she identifies, or just how she feels? What if, becoming a woman, she has not been able to, or even wanted to, completely leave the dude behind, in part because she was famous first as a dude? Would anyone know who Caitlyn Jenner was if she hadn’t first been Bruce Jenner? Is it not alright for her to call up that history? Or to see her transformation in material terms — as being in part about the body and appearance, as about what gender “looks like?” Or . . . here’s a radical thought . . . to joke about something so serious?

And, more to the point than what she may or may not want: Not to give her too much credit, but what if her playing with this phrase publicly undermines its dangerous power? Or what if it acknowledges, however indirectly or unintentionally, a history of masculine privilege that she has not entirely shed? Plus, Steven Tyler looks like a lady too, with his sweet and lovely features, fancy mouth, smoky eyeshadow, luscious long hair, necklaces, and shirt-cut-down-to-there. Who is the real dude, and who the lady here?

Who cares? I do. Because my queer students are so fragile, so easily hurt, and I am worried about them — and not in the way that they want me to be. Because when I say to one of them, “Being a victim is not hot, and in my day a political platform based on being a victim would never have gained traction,” she seems startled but retorts that on the contrary, victimhood is hot, adding, “What about BDSM?” And so I explain that BDSM is not about being a victim, it’s about moving beyond and transforming victimization — for those who come to it that way — and it’s about destabilizing the grounds of victimization, through playing with power. Which is also what drag is about in its way. And I am shocked to find myself in the position of defending, to a queer, the value of hotness — as shocked as she seems to be at the idea that hotness could be the point of queer culture.

I don’t believe her. I don’t believe that she really finds victimhood hot, unless . . . is this a new fetish that is hopelessly lost on me since I’m almost 50? I won’t — I can’t — believe in the victim as the new face of queer culture. What were all those drag queens at Stonewall fighting for, anyway? If victimhood is hot, then we have lost.