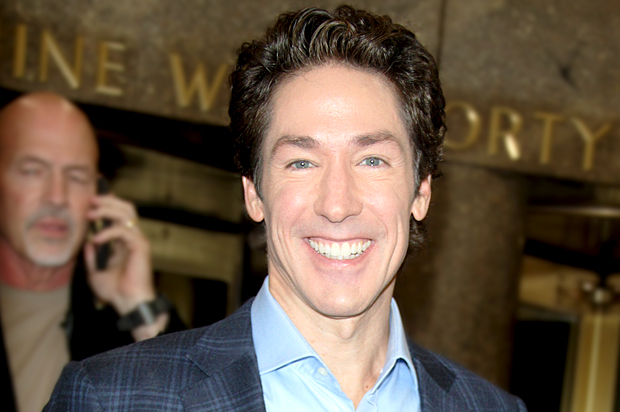

On Monday, millionaire pastor Joel Osteen taught more Americans via his actions than he’ll ever do in a sermon. At least initially, Osteen refused to open the doors of his Houston megachurch to people displaced by Tropical Storm Harvey. Even though he eventually reversed himself and defended his conduct in evasive media interviews, Osteen’s message was clear: Don’t count on religious leaders to do what’s right.

We asked Joel Osteen why he waited days to open his famed #Houston mega-church for evacuees of #Harvey. Here's what he said. pic.twitter.com/CWxe3qufJo

— Kaitlin (@kaitlinmonte) August 30, 2017

That message is one that many have been hearing for quite some time, as American Protestantism has moved from focusing on humble public service to greed and naked political ambition. Some, like Dallas pastor Robert Jeffress, manage to pursue both simultaneously. In 2013, he finished construction on a $130 million church campus in Dallas, a project which he claimed was about glorifying God, instead of mammon.

“In these tough economic times, we wanted to use our gifts to build a church that provides spiritual growth and healing while seeking to reflect the splendor and majesty of God,” he said at the time. A year earlier, he had claimed that then-president Barack Obama was “paving the way for the future reign of the Antichrist.”

Jeffress made those comments during the 2012 election campaign, in the context of his support of that year’s Republican nominee, Mitt Romney. Just four years prior, the Baptist minister had claimed that Romney’s Mormon faith was a “cult” whose members were going to hell. In a 2016 move that surprised no one, Jeffress was one of Donald Trump’s earliest endorsers.

Osteen is different from some of his evangelical colleagues in that he has generally shied away from political involvement. Despite having called Trump “a friend of our ministry” and “a good man,” he has not endorsed political candidates. What Osteen has endorsed, however, is what many critics have called the “prosperity gospel,” the idea that God not only wants to bless believers spiritually but wants to bless them financially as well.

“We just feel like this is God’s blessings,” he said during a 2012 interview with Oprah Winfrey. “You know, we’re big givers, we live what we preach, we’ve given millions of dollars. And I don’t think there’s anything wrong with having a nice place to live and being blessed.”

To his credit, Osteen does not draw a salary from his Lakewood Church nor does he directly ask his fans for money, unlike many other ostensibly religious organizations. Last year, a Canadian religious group called Gospel for Asia was accused of absconding with more than $90 million in donations. Nonetheless, Osteen’s followers have certainly ponied up bigly. His organization reportedly has an annual budget of more than $70 million, and the church facility he originally declined to open up to flood refugees was previously the home arena of the NBA’s Houston Rockets.

Osteen’s views on wealth and his ostentatious style (he lives in a $10.5 million mansion and is estimated to be worth about $40 million) are a pronounced departure from traditional Christian teachings about “the love of money” being the root of all evil, how difficult it is for a rich person to live a life worthy of God and how the materially disadvantaged are regarded more favorably by the divine.

Osteen’s theological indifference seems to be reflected not just in his initial refusal to follow Jesus Christ’s directive to care for “the least of these my brethren” but also in his apparent lack of preaching interest in Christ himself.

In the Google Play version of Osteen’s latest self-help offering, “Think Better, Live Better,” a search turns up 599 matches for “God” but only 45 matches for “Jesus” or “Christ.”

A search through Osteen’s Twitter feed reveals that he almost never mentions Jesus to his digital flock. Generally speaking, he only mentions the name of his alleged savior around Easter, never around Christmas. In fact, within the past three years, he has mentioned “Jesus” or “Christ” only 14 times amid hundreds of tweets. (By contrast, Rev. Billy Graham has mentioned “Jesus” and “Christ” dozens of times this year alone.)

Perhaps unsurprisingly, one of Osteen’s divine name-checks came during the firestorm of criticism he provoked on Monday. Here is the full list:

Jesus promises us peace that passes understanding. That’s peace when it doesn’t make sense.

— Joel Osteen (@JoelOsteen) August 28, 2017

Jesus didn’t come to start a religion. He came to have a relationship with you. He has a purpose and a destiny for your life.

— Joel Osteen (@JoelOsteen) April 17, 2017

The nails didn’t hold Jesus on the cross. Love held Him on the cross. He did it for you. He did it for me.

— Joel Osteen (@JoelOsteen) April 16, 2017

When Jesus hung on the cross, He took all your mistakes, all your failures, all your weaknesses and He forgave them.

— Joel Osteen (@JoelOsteen) April 15, 2017

Jesus didn’t call us to judge people, He called us to heal them, to restore them. He called us to become their miracle.

— Joel Osteen (@JoelOsteen) April 15, 2017

Jesus didn’t come to start a religion. He came to have a relationship with you. He has a purpose and a destiny for your life.

— Joel Osteen (@JoelOsteen) March 27, 2016

Being right is overrated. Jesus said, “Blessed are the peacemakers.” He didn’t say blessed are those who are right.

— Joel Osteen (@JoelOsteen) October 20, 2015

The nails didn’t hold Jesus on the cross. Love held Him on the cross. He did it for you. He did it for me.

— Joel Osteen (@JoelOsteen) April 4, 2015

Jesus didn’t call us to judge people; He called us to heal them, to restore them. He called us to become their miracle.

— Joel Osteen (@JoelOsteen) April 2, 2015

You are righteous right now. Not because of what you’ve done, but because of what Christ has done.

— Joel Osteen (@JoelOsteen) June 10, 2017

Christ took your sins. He paid the price for every mistake, every wrong. His blood covered it once and for all.

— Joel Osteen (@JoelOsteen) April 14, 2017

Don’t say, “I can’t do it.” The right attitude is, “I can do all things through Christ.”

— Joel Osteen (@JoelOsteen) October 4, 2016

You are self-sufficient in Christ’s sufficiency. Don't rely on people, rely on God.

— Joel Osteen (@JoelOsteen) June 5, 2016

Christ took your sins. He paid the price for every mistake, every wrong. His blood covered it once and for all.

— Joel Osteen (@JoelOsteen) April 5, 2015

Osteen’s secular preaching has been noticed by so many Christians that a satirical article published last year about him supposedly apologizing for mentioning Jesus in a sermon went viral when people mistook it to be an actual news story.

Rafts of political science research have demonstrated that American churches’ doctrinal views have driven away people who want their faith to be more receptive to scientific evidence on issues like homosexuality or evolution. The Religious Right’s vociferous attempts to merge evangelical Christianity with far-right political opinions have also made those with moderate or liberal views look elsewhere for moral discussion.

It’s also clearly true that some religious leaders’ attempts to cash in on their followers’ need for validation and their displays of callous indifference to suffering — both of which are exemplified by Osteen — are part of the reason why nearly 24 percent of Americans now say they have no religious affiliation, compared to just 3 percent in the 1950s.

“Hypocrisies and conflicts in church, when they (inevitably) erupt, don’t just drive people to other churches, as in the past, but sometimes take them out of Christianity altogether,” Georgia pastor David Gushee wrote last year. He’s exactly right.

As the Pew Research Center’s Michael Lipka noted in 2015, this process is only accelerating as people who say they’re not a part of any religious tradition are not only becoming more numerous, they’re also becoming even more skeptical of religion itself.

Presumably, these trends ought to bother people like Joel Osteen and Robert Jeffress. Apparently they have other things on their minds.