Last Monday, the Washington Post ran a short article headlined “Israeli Official: Netanyahu Must Push Trump to End Iran Deal,” which covered remarks made by Yisrael Katz, Israel’s minister of intelligence and strategic affairs, at a conference near Tel Aviv. Perhaps signaling what to expect when Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu travels to New York this week to attend the UN General Assembly, Katz advised his boss to press President Donald Trump to alter or walk away from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), commonly known as “the Iran nuclear deal.”

According to the story, Katz used the North Korea crisis to make the case that the JCPOA is defective and in the process declared that “Iran is the new North Korea.” That Israel’s leaders are counseling the Trump administration to change or bust the Iran deal is hardly news. They spent the better part of President Barack Obama’s second term in office lobbying against the diplomacy that led to the deal and then working to undermine the JCPOA after it became a fact of life.

It is also not exactly news that the Israelis have legitimate reasons to be concerned. The Iranians routinely threaten Israel and seemed determined to develop nuclear technology, at least until the JCPOA. Hezbollah, the Lebanese terrorist group, functions as an Iranian expeditionary force fighting in Syria, Iraq, and even Afghanistan, and has tens of thousands of rockets that can reach every part of Israel. This is particularly troublesome for the Israelis on two levels. First, there is the obvious specter of mass civilian casualties and infrastructure damage that those rockets can do to Israel. Second, the combination of a nuclearized Iran and a well-armed Hezbollah greatly diminishes Israel’s freedom of action to pursue its interests.

Since the Egypt-Israel peace treaty, the Israelis have acted with impunity around the Middle East as they saw fit. It has not always worked out well, but that's beside the point. Israel faced few constraints when it decided to bomb Iraq’s nuclear facilities in 1981, invade Lebanon in 1982 and take out a Syrian nuclear facility in 2007. The combination of Iranian nuclear weapons plus Hezbollah, which represents Iran’s second-strike capability, severely compromises Israel's ability to respond to threats. Yet while Katz’s alarm about Iran’s nuclear program is well grounded, his logic seems less so.

One could argue that North Korea now poses such a threat to South Korean, Japanese and American interests in East Asia precisely because there is no similar agreement to keep a lid on Pyongyang’s nuclear program as the JCPOA is presently constraining Iran’s nuclear program (though not Tehran’s capacity to make mischief in other ways). There was, of course, the 1994 "Agreed Framework," under which the North Koreans agreed to halt the development of nuclear reactors that were believed to be part of their proliferation efforts, in exchange for reactors that could not be used for those purposes and for fuel oil. It worked for a while, but the combination of North Korean missile tests and a policy review in 2002 by the Bush administration that found the North Koreans to be cheating led to the end of the agreement. If Katz was making the argument that the JCPOA will eventually go the way of the Agreed Framework, he may have a case. But he is getting ahead of himself.

Debate over the JCPOA in Washington is typically polarized. Opponents claim that it is so deeply flawed that it was bankrupt from the start. The Iranians, they argue, have no intention of permanently mothballing their drive to develop nuclear technology. Iran hawks point out the acceleration of Iran’s missile development (not addressed in JCPOA, but subject to sanctions) as evidence of Tehran’s malign intent and continuing threat. The consolidation of Iran’s power and influence around the region — including of course the arming of Hezbollah — suggests that Iran is a bad actor that is not to be trusted.

Iran doves respond that there was no other way to arrest Iran’s nuclear development; that Tehran would be closer to nukes today if not for the JCPOA; that the deal gives the United States, Europe and Israel some breathing room for additional diplomacy and development of counter-measures, if necessary; and that bringing Iran in from the cold will improve regional security, obviating the need for Tehran (or anyone else) to possess nuclear weapons. This last point is based on an underlying logic of the deal, which bets that Iran will become a different country in the decade before the restrictions on its nuclear program are scheduled to come to an end.

Both camps make compelling arguments, creating a lot of ambivalence in between. It is unclear what the Trump administration is going to do, but it has now twice certified that Iran is upholding its commitments as outlined in the JCPOA, thus holding off on new sanctions. Although there has been a lot of tough rhetoric about Iran inside the Beltway recently, there is also a fair amount of support in favor of the status quo. These folks are supporters of the JCPOA by default. They regard the deal as a fact of life, even if it is flawed in certain and important respects, and fear that walking away would permit the Iranians to move forward with nuclear development under far fewer constraints than those imposed upon them under the JCPOA. That's where Yisrael Katz’s logic in declaring Iran the new North Korea runs off the rails.

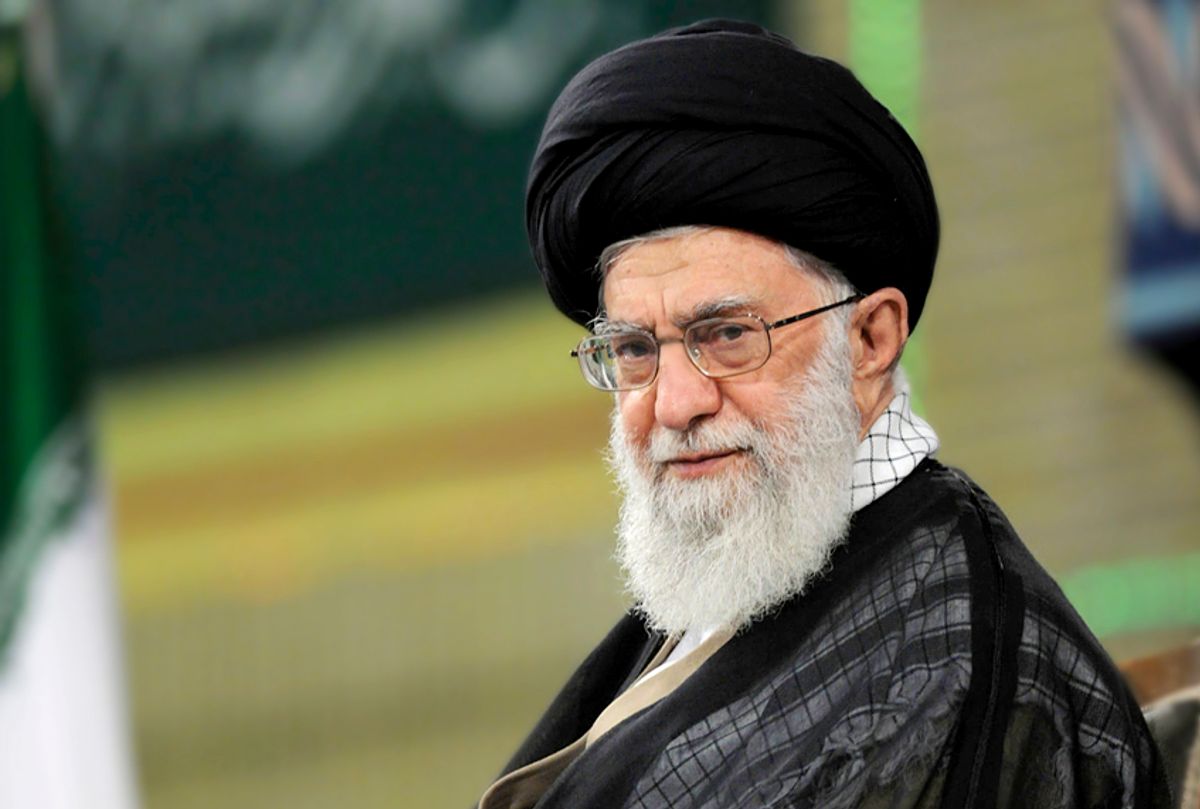

Kim Jong Un has a bomb, but Ayatollah Ali Khamenei does not. What is the difference between them? There is no broad multilateral agreement specifically targeting North Korea’s nuclear program like the one in place that seeks to prevent Iran’s proliferation. Maybe the history of the Agreed Framework proves that North Korea is immune to these kinds of efforts. Its leadership has demonstrated a willingness to let its people suffer enormously in the service of the regime’s goals. The Iranian leadership has also inflicted pain on that nation's citizens, but they have also demonstrated that they are susceptible to both international pressure and incentives to freeze the Iranian nuclear program. It may be that Iran, like North Korea, is determined to obtain nuclear weapons no matter what, but so far, at least, Tehran is not following Pyongyang’s example. That does not mean that there is great reason to trust the Iranians, but it is exactly why the Iran nuclear deal, with its elaborate mechanisms for verification, is so important.

Shares