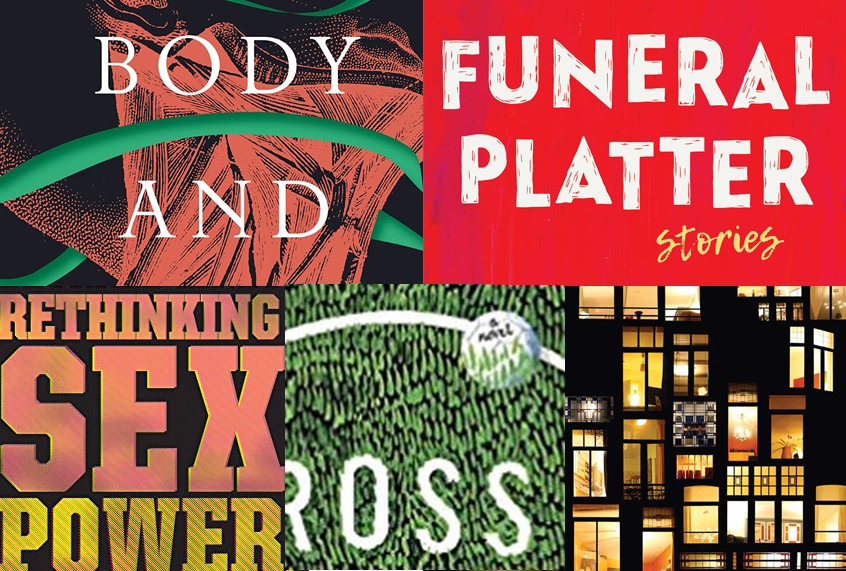

For October, I posed a series of questions — with, as always, a few verbal restrictions — to five authors with new books: Greg Ames (“Funeral Platter“), Panio Gianopoulos (“How to Get into Our House and Where We Keep the Money“), Vanessa Grigoriadis (“Blurred Lines: Rethinking Sex, Power, and Consent on Campus“), Carmen Maria Machado (“Her Body and Other Parties“) and Ross Raisin (“A Natural“).

Without summarizing it in any way, what would you say your book is about?

Carmen Maria Machado: The nightmares and pleasures of the body. The furniture of gender’s haunted house. Sex as creative act and loss. Death. The mind as prison and liberator.

Panio Gianopoulos: Envy, infatuation, people making entertainingly stupid mistakes, vandalism (actual and emotional), love triangles, crisis, self-revelation.

Ross Raisin: Locker rooms. Banter bubbles. Identity. Thwarted ambition. Desire. An enormous fish. A subtle (I hope, at least) male G-spot sex scene.

Vanessa Grigoriadis: The messy, muddy early sexual experiences of four-year residential college students. The terrifying and traumatic subset of those experiences that change lives. Above all, a belief that my gonzo reporting trips to college campuses could sort out a misinformation campaign about sexual assault by the radical left and the misogynistic right.

Greg Ames: Online dating, ventriloquist dummies, addiction, Taco Bell, despair, intimacy, rogue puppies, love, loss of love, God, laundry, obsession, Kafka, fantasy, literature, childhood, rupture, scrambled eggs, sobriety, solace, death. Plus, the confusion around, fear of, and desire for connection.

Without explaining why and without naming other authors or books, can you discuss the various influences on your book?

Raisin: Young people. The constraints put upon them by society and institutionalization. The glaring absence of openly gay sports stars. Thirty-plus years of supporting a failing soccer team. Deep research into enormous fish. My friend Johnny’s extremely frank male G-spot anecdotes.

Gianopoulos: A tiny dog in a purse, the Pacific Coast Highway after midnight, yurts, a 60-year-old surfer putting her silver hair into a ponytail, small-circle jujitsu, my daughter walking bare foot through a creek.

Grigoriadis: Nights at weird Airbnbs on the periphery of college towns. Drinking cheap vodka at frat parties while making stilted conversation with students who didn’t realize that I graduated from college the year they were born. The election of the groper-in-chief. My horror that culture wars on campuses are part of why America elected the groper-in-chief.

Machado: Fairy tales, the uncanny, horror movies, mid-century women writers, feminism, queer theory, children’s books, my grandfather’s storytelling, my wife.

Ames: There are so many. One big influence was Marvin Lahood, a life-changing professor who taught at my college in Buffalo, a state school where the only two requirements for admission were, I think, a pulse and 500 bucks. I slouched in the back row of my classes for two semesters, stoned and/or drunk, before I wandered into Marv’s orbit to take a summer make-up class. His passion for reading prose and poetry, his spark, gave me permission to pursue my own. He opened my entire system to literature and encouraged my mind and my pursuit of writing. I was never the same after that class. “Funeral Platter” is my second book, and I have two more on the way, all because this teacher saw me and took me seriously.

Without using complete sentences, can you describe what was going on in your life as you wrote this book?

Ames: Wanting to die and wanting to live.

Grigoriadis: Broke my knee; suffered from severe morning sickness; gave birth. Death. In the space of a few months, my father died and a plane carrying my best friend and her two children disappeared.

Gianopoulos: Moving away from New York, marriage, three children, graduate school, many careers, the loss of my parents, moving back to New York.

Raisin: The birth of my daughter, colic, messy tired devotion, a jilted cat, a surprising and exhilarating run to the final of the League Cup (you don’t know what that is, but that’s okay), the birth of my son on the sofa.

Machado: A new start, followed by happiness, followed by pain and chaos, followed by another new start, followed by a slow and unyielding bliss.

What are some words you despise that have been used to describe your writing by readers and/or reviewers?

Grigoriadis: The more hurtful or unfair a thing is, the more it’s your job to let it go, your mission to let it go. A spiteful, intellectually dishonest review can be enraging, and those feelings can become an obsession. Then, you are drinking poison and hoping someone else gets sick.

Machado: That my work is “barely genre.” Like, what does that even mean?

Raisin: I’ve never read a review of my work, but I’ll take a punt at “perverse.”

Ames: I try not to read reviews because I already have a committee of opinionated voices in my head. If people don’t like it, I might begin to agree with them. When we’re all ganging up on me, that’s bad for my self-esteem.

Gianopoulos: Poignant: I picture someone weeping softly into a handkerchief.

If you could choose a career besides writing (irrespective of schooling requirements and/or talent) what would it be?

Raisin: I don’t think I’m that fussed about the idea of “career.” Work experience is another matter, though, and the work experience I most crave is the one that I left behind to write: restaurant work — being part of a team, in and out of each other’s pockets. Working beside another person to the point of sweat is a very bonding thing, and may have some relation to why I’ve just written a novel about a sports team.

Gianopoulos: The astronaut who doesn’t go first into the scary portal, beneficent cult leader (nothing pervy).

Grigoriadis: Classical musician.

Ames: A cat burglar? (I’m not sure what that is.) Honestly, I wouldn’t rather be anything else. I’ve wanted to be a writer since I was a little kid. And I find that teaching at a university fuels my writing. I get to read, talk about literature and guide students down the path of inspiration and writing. That’s nothing less than a great fortune.

Machado: Lounge singer.

What craft elements do you think are your strong suit, and what would you like to be better at?

Machado: I think I’m a decent prose stylist, and I desperately wish I was better at dialogue.

Grigoriadis: I’m a reporting obsessive. I could be a better sentence-minder.

Ames: I feel at home when I write fiction and so far have been able to spool out a parade of weird characters and dialogue in approachably absurdist scenarios. When I try to write nonfiction, though, the words turn to dust. I haven’t yet figured out how to get them to do what I want. I’d like to figure out how to access that easy flow in a long nonfiction piece I’m trying to write about my childhood in Buffalo, but a part of me remains fiercely resistant to this project.

Gianopoulos: I’m pretty reliable with odd metaphors and psychological insights, especially embarrassing ones. I’d like to learn how to broaden the scope of a narrative, to move from the single characters that I tend to write to a sprawling, complex, multiple character approach. Also, I dream of one day embracing sentence fragments — my high school English teacher beat them out of me, and I still flinch when I try to write one.

Raisin: I’m content that each of my novels is a large stylistic and subject departure from anything else I’ve done; though that does in turn mean that I am continuously in search of elements to be better at.

How do you contend with the hubris of thinking anyone has or should have any interest in what you have to say about anything?

Gianopoulos: Have you seen social media? Can’t be worse than that.

Ames: I’m just at play with words and trying to make myself laugh or sneak up on myself with a surprising turn of phrase. I’m not really adept at courting publicity or marketing myself, to the chagrin of the people who are trying to help me build a brand or platform or whatever. Composition excites me. It gives my life purpose and meaning. I love knowing I have raw pieces in my hard drive. They have so much promise. I can still make them better, funnier, deeper. Publication, for the most part, and everything that it entails, is kind of a bummer. I’d much rather be hunched over my desk, trying to put the words in the right order.

Raisin: It’s not a thought that’s ever occurred to me.

Grigoriadis: I’m interested in promptly unfurling plot points, not warping minds with pronouncements. I’m a journalist in the Hunter Thompson and Tom Wolfe tradition of show don’t tell.

Machado: I don’t consider it hubris? I think I have something worthwhile to say. If I didn’t think that, I wouldn’t have tried to publish a book. Trying to publish a book without having something worthwhile to say — that’s hubris.