The windowless basement of the Buffalo Grove Family History Center had the feel of an underground bunker—fluorescent lights, cinder block walls, the musty scent of dampness. At the room’s entrance sat a gray-haired woman, birdlike and benign. With robotic precision, she meted out instructions on how to use the machines, where the microfilms were located and how to order original documents. She appeared as nondescript and gray as the walls.

I’d come to the family history center in search of my grandfather Azemar Frederic. I was between adjunct college teaching jobs, applying for tenure track teaching positions in creative writing, and working part-time as an assistant editor for a medical journal. The year before, I’d been offered a position in creative writing at a liberal arts college in Tennessee. But I turned it down. Uprooting my life at the age of forty-nine for a position that paid in the low five figures seemed foolhardy. My husband would need to obtain a Tennessee dental license to practice dentistry, and we would have to pay out-of-state tuition at the University of Illinois for our daughter Lauren. So I resigned myself to seeking positions in the Chicago area where the competition was especially rigorous and my chances for success slim.

I had time on my hands and an insatiable longing to find Azemar who over the years had become more and more unreal to me as if he never existed, was a figment of my mother’s imagination. Without a photograph of him, I had nothing physical to connect him to me. This need for a physical image of him was primal. It was an aching absence that I needed to fill.

This was 1995, before the Internet, before Ancestry.com. Family research required a journey, was a physical as well as an emotional quest. I’d arrived at 10 a.m. when the center opened. I would stay as long as it took to find my grandfather Azemar Frederic of New Orleans, my mystery man.

But I had little to go on. I didn’t know when he was born or when he died. My mother couldn’t or wouldn’t help me. Her memory faltered when it came to her father.

“He might have died after you were born. I don’t remember. Maybe in the 1950s.”

What I did know wasn’t much, birth and death place—New Orleans and the precise spelling of his first and last name. As a child my mother would spell out her maiden name for me—a school requirement on this form or that. Always stressing that there was no k at the end of Frederic. “That would make us German. And we’re not German,” she’d say. “We’re French. And your grandmother Camille Kilbourne is English and Scottish.” Her tone was fierce and not to be challenged. She took great pride in her French heritage, occasionally throwing out a French phrase to prove her point: tante/aunt, très bon/very good, n’est pas/isn’t it so.

Persistent over the years, I pieced together other sparse facts about the elusive Azemar—even his name conjured mystery. My mother had a shorthand way of describing him: hard worker who didn’t smoke or drink. He and my grandmother divorced early in their marriage. They both remarried and started families.

My mother never spoke of her father’s second family when I asked about them, except to say the oldest daughter resembled her. I didn’t know how many other children there were from Azemar’s second marriage or who his second wife was. My mother refused to talk about them. The mere mention of them made her go quiet.

“People say I looked like him,” my mother would say, placating me as if her face replaced the one I desperately wanted to see. Then she’d add, her eyes far away, “I asked my mother once why she didn’t stay married to my father. And she said, ‘he was too jealous.’”

And as often happened with my mother’s stories, the not telling was the telling. If I’d been older, I might have picked up on her clues. But I was a child. I accepted what she told me. She was my mother.

The morning wore on. Time passed without notice as I scrolled through the microfilm finding Fredericks, Fredericos but no Frederics. Every once in a while I’d have to stop scrolling and close my eyes. The whirling of the microfilm and the low lights were making me queasy or maybe it was the gnawing hunger that I refused to placate. I was a woman on a mission.

It was almost 1 p.m. I’d been there for three hours and hadn’t found Azemar. I decided to finish the 1900 Louisiana census record and return next Wednesday.

The surname Frederic happened first. It jumped out at me, spelled exactly as my mother said: C, no K at the end. Then I spotted my grandfather’s unusual first name Azemar at the bottom of a long list of other Frederics. In 1900 Azemar Alfred Frederic was three years old and listed as a granddaughter, sex male. Finally I knew when he was born: 1897. A flutter of elation ran through me as I jotted down his information on a legal pad that until now was woefully empty.

There were many family members living in the Girard/Frederic household. Azemar’s father was Leon Frederic, his mother Celeste Girard Frederic. I savored the beauty of her name, my great-grandmother Celeste Girard. Azemar was the youngest of five children: Louise, Leon, Leonie, and Estelle. They lived at 379 Ursuline Avenue in New Orleans. The head of the household was Albert Girard, Azemar’s maternal grandfather, my great-grandfather. There were also a number of Girards sharing the residence.

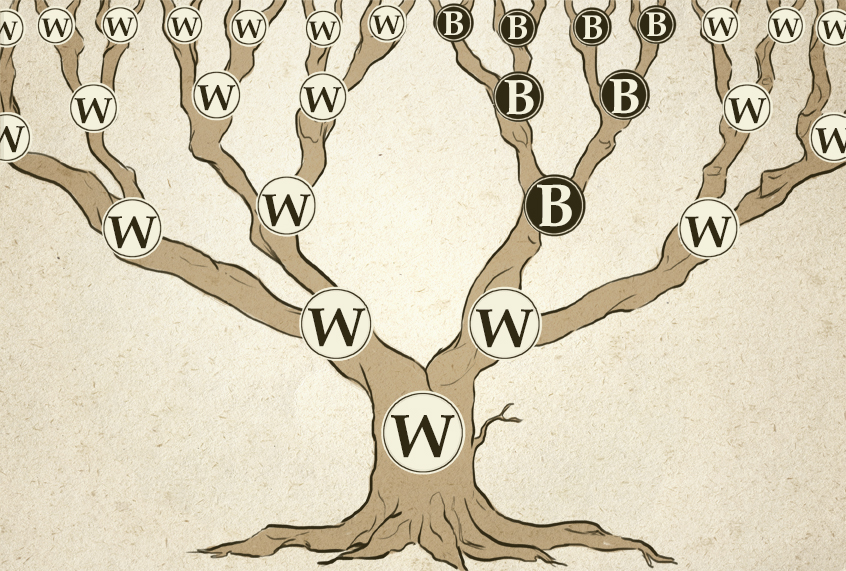

As I traced across the grid, I stopped on the letter B, perplexed by its meaning, then I scrolled up to find the category: Race.

My mind didn’t quite take in what I was seeing. Would the census taker use B for black in 1900? It didn’t seem likely. Then what did B mean if not black? And why would the census taker mark my grandfather and his family black? It had to be a mistake. My grandfather’s family was not black.

Aware of the time, I hurriedly searched for Azemar in the 1930 census. When I found him, his race was no longer designated as B, now his racial designation was W. I was familiar with the one-drop rule, a racial classification asserting that any person with even one ancestor of African ancestry was considered to be black no matter how far back in their family tree. But the B perplexed me, as did the W. How could Azemar be black in 1900 and white in 1930?

I glanced back at the gray-haired lady. She was shuffling through index cards, keeping herself busy, and looking bored. I got up from the machine and walked over to her.

“I was wondering about the racial designation B in the 1900 Louisiana census. Can that be right?” I asked reticently, purposely not mentioning that the B was attached to my mother’s family.

“Those cards have been copied. B means black.” She looked me up and down. “You know the saying, ‘there’s a nigger in every woodshed.’”

I was speechless. Struck dumb.

She laughed, a tight pinched laugh full of malice. “Things were different back then. We had those candies, you know, we called them ‘nigger babies.’” She said this with some glee in her voice as if we were sharing the same joke.

The word nigger kept reeling from her mouth like the rolls of microfilm whirling around me. I stood there, stunned, having no idea what the woman was talking about or how to respond. I’d never heard of “nigger babies.” And if I had, I’d never be spewing the term out like a sharp slap.

All I could muster in defense of a family whose race I’d just discovered and was unsure of was a fact that sounded like an excuse. “In Louisiana,” I muttered, “you only had to have one drop of black blood to be considered black.” I felt assaulted with an experience I had no way to relate to and that I wasn’t certain I could even claim.

She finished my thought for me as if confirming what she’d already said about race and blood. “Yes, just one drop was all that was needed. You know the saying, ‘nigger in the woodshed.’”

She seemed to think I agreed with her, that the one-drop rule was correct, leaving no doubt about my race and in her eyes my tainted blood. It was evident to me it would be useless to continue this conversation with this bigoted God-lugging woman.

For a long second she stared through her glasses at me as if she was searching for a physical confirmation of my heritage. “Oh,” she finally said as if a light bulb had gone on in her head, “You’re the one with the slaves in your family.”

Slaves? I never said anything about slaves in my family. She’d made her own logical leap—black ancestry equaled slaves. This was a logical leap I was not prepared to accept. This was not how I saw my family or myself. Shaken, I returned to the microfiche machine, rewound the role of microfilm, placed it back in its box, and refiled it in the steel drawer, avoiding the woman like a contagion, afraid of what other derogatory racial expressions she’d resurrect from her arsenal of bigotry.

Outside, the cold January wind was like a tonic, snapping me back to the ordinariness of winter—snow and cold, the need for shelter. I hurried to my car, shut the door, and started the engine. But I didn’t leave. I sat staring at the silvery sky, the mottled clouds, the uncertainty of light that made a Midwest January day bearable—when the sun disappears for days.

What just happened? I felt like I’d had an out-of-body experience. In a split second I became someone else, my identity in question. When I walked into the squat, brown building I was a white woman. When I left I didn’t know who I was. Was I still a white woman but a white woman with black ancestors? Were Azemar Frederic and his entire family the “niggers” in my woodshed?

Why hadn’t my mother told me? Was this the reason she didn’t have a picture of her father, fearing I would see the physical evidence of his blackness? That I would see what she’d been hiding? Was this why she never took us to New Orleans to visit her family?

I couldn’t get it into my head that I wasn’t who I thought I was. I wasn’t this white woman. Or I was this white woman who was also this black woman. Or I was neither? Who was I really? And what did my racial mixture mean?

As I pulled out of the driveway, I glanced at myself in the rear view mirror. Nothing had changed. I looked the same. Anyone could see what I was.