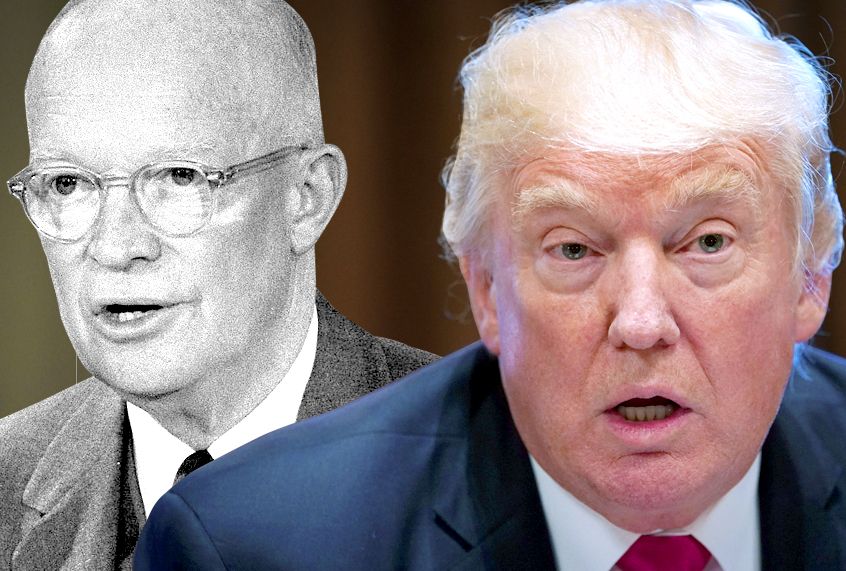

What happens when someone with the temperament and knowledge-deficiencies of Donald Trump is backed into a corner? Let’s hope we don’t find out.

Humility in a leader is a noble thing. We prefer to believe that it comes about more often in a democracy than in any other form of government, because it should. President Dwight Eisenhower attributed to a former teacher an axiom he took to heart and never forgot: “Always take your job seriously, never yourself.” Eisenhower, a professional soldier, had warily sent men into battle on D-Day. “The hopes and prayers of liberty-loving people everywhere march with you,” he told them. He wasn’t thinking about himself, or his personal legacy.

Humility’s unworthy opposite, hubris, is a quality we’re accustomed to in public life. Whenever the prospect of war looms, we should be especially worried. Hubris is a degenerative disorder that rarely, if ever, ends well. Before jumping to conclusions, though, in a way, it doesn’t matter that Donald Trump combines tough talk and peevishness with crude theatricality, immaturity, a short attention span and a scary ability to tell comforting lies to himself. There is nothing new about the hubristic presidency.

The Bush-Cheney administration invaded Iraq, even though Saddam Hussein’s regime had no relationship to 9/11. A mature, politically savvy Richard Nixon conducted the rash and devastating “Christmas bombing” of Hanoi, supposedly to bring the Vietnamese enemy to the negotiating table. Elected, to some degree, because of his “secret plan” to end the war with American honor intact, he dropped millions of tons of bombs, killed some 1,500 Vietnamese civilians over that one Christmas and went on to dig a hole for himself that we all know about. More than a little hubris was involved.

Assurances are hard to come by. The late journalist David Halberstam’s iconic measure of bad decisions issuing from “the best and the brightest” is a lesson that should not be forgotten. John F. Kennedy gets high marks for avoiding a nuclear event with the Soviet Union. But after the Cuban Missile Crisis, Bobby Kennedy ruminated with an interviewer as to the collective wisdom of the individuals who were present when all the options were laid out before his brother, the president: “We had among them the most able in the country, but if any one of the half-dozen of them were president, the world would very likely have been plunged into a catastrophic war.” That’s how important the chief executive is. His judgment is the reason why he is where he is. Theoretically.

Not since an unprepared Harry Truman became president and made the decision to drop atomic bombs on Japan has an inexperienced American leader been in a position, as Trump is now, to launch an attack of comparable magnitude. In 1945, at least, America was united in the prosecution of a war it had not initiated, a war it had steered clear of until other options were exhausted. Atomic holocaust occurred at the end of years of fighting and outrageous numbers killed across Europe and Asia.

Today, a high level of moral condemnation already precedes the prospect of military action. That’s a good thing, because the symbol of American power these days is a real estate developer known for golf courses, casinos and a Moscow beauty pageant; he’s a gambler with other people’s money who exhibits poor personal judgment. Ours is more than a moment of sharp division; it is an era of such previously unimaginable perversion and distortion of the framers’ intentions that it requires spiritual rescue as much as political rescue. There is a germ of hope in the slender majority in this country, and a much larger majority among our allies, who are clear-headed and devoted in all respects to the health of the planet and its sentient beings.

A certain percentage of the trusting who thought they’d voted for that amorphous political good called “change” are slowly giving up on Trump and his gang of pain-inducers. Some will keep pretending, hubristically, that power is right where it belongs, while many others realize (in an increasingly visceral way) what the United States must overcome in order to be restored to a minimal level of moral competence as a player on the world stage.

At this juncture, liberal humanism is beginning to reassert itself, because it is the only apparent antidote to Trumpism. Recent speeches by George W. Bush and Barack Obama have doubled down on this call for harmonious dialogue, civilized manners and essential tact. Compassion toward the neighbor we do not know, or toward the stranger speaking a language we do not understand, is the right thing to feel. As Gen. Eisenhower (and, yes, Gen. John Kelly), and others who served remind us, soldiers have learned that moral community, the circle of trust, is literally life-saving. Civil society (assumed safe, protected, and only policed as necessary) struggles to learn the same truth.

Our founding documents contain a call to locate that spirit of respect for social bonds and human dignity. In Adam Smith’s influential “Theory of Moral Sentiments” (1759), a favorite of the founders, the author had some germane foreign policy advice: “When two nations are at variance, the citizen of each pays little regard to the sentiments which foreign nations may entertain concerning his conduct. His whole ambition is to obtain the approbation of his own fellow-citizens. . . . He can never please them so much as by enraging and offending their enemies.”

It is too easy to march off to battle after a shouting match. Nowadays, we call that “playing to the base.” The philosophe Smith goes on to declare that domestic hatreds are even easier to exploit: “The animosity of hostile factions . . . is often still more furious than that of hostile nations. . . . A true party-man hates and despises candor.” One can only conclude that world wars and wars on terror have not made us either safer or nicer. “Of all the corrupters of moral sentiment,” Smith concludes, “faction and fanaticism have always been by far the greatest.” So much for political evolution.

We know the clear and present danger — at least you do if you listen to smart people in the field of diplomacy who have sounded alarms. The childish and tyrannical creature of an entertainment-driven news media is in the Oval Office and out of his league. He grew up with much, materially, and didn’t feel he needed to study the wisdom that history has imparted. If he could manipulate facts to suit himself, he didn’t have to even feign humility. Or give back. He always wanted more for himself, and that wanting took precedence over everything, certainly over the public good. That’s why we have this sinking feeling about where he might take us, so as to prove something to himself.

That wanting in him produced a my-way-or-the-highway, sue-or-be-sued liar and grifter, someone bored with life when it wasn’t feeding his appetite for fame and reaping him personal rewards. Friends were those who served his interests. Women were to be used. In a now-infamous 1994 interview, he actually said this: “Other than raising your kids to be your primary legacy, everything else seems futile. Doing a good or bad job doesn’t matter. I do what I do because there’s nothing else to fill the time.” The Electoral College has given a harmful man, who sees the world as a black and white, win-or-lose, humiliate-or-be-humiliated jungle environment, a license to kill (or be killed).

Will he start something? The year 1967, 50 years past, witnessed a massive buildup of U.S. forces in South Vietnam, taking sides in a civil war without “good guy” leaders. The CIA was deeply pessimistic about final victory, but the military brass who exaggerated enemy losses offered a less problematic perspective, and President Lyndon B. Johnson waded deeper into the deadly swamp. The spiritual suffering that occasioned back home led to a mobilization of antiwar protesters (strengthened by the voices of antiwar veterans, priests and nuns). “Give peace a chance” was the chant that launched a call for spiritual renewal. As tough a fellow as LBJ was, and as sensitive as he was to addressing poverty and racism in America, he had no moral answer to the just call for the recovery of our humanity as a culture, one nation among nations.

Obviously, Donald Trump, the sycophantic Mike Pence and the emboldened right wing bear no resemblance to Johnson and his liberal vice president, Hubert Humphrey, who wanted to stop what they’d started but couldn’t. As for Trump-Pence? What chance do we have to pull back from any action they initiate? Humanity is not really their thing. Guilt is something they ascribe to others. Regret is seen as weakness. The only check on executive-directed aggression lies, it would appear, with a select few men in uniform — “my generals,” in Trump-speak. We hope for an Eisenhower, or a platoon of them. But is that realistic?

Saber-rattling does not become a great nation. Trump and Pence, singly and together, have given off enough bad vibes to signal their arrogant and unreasoning approach to governance generally. One is impulsive, the other rigidly evangelical. Neither can be trusted to reason through international crises.

We can expect reasonable answers only from those who are deliberative and are repelled by dogma — a characterization synonymous with the humanist tradition. We try to avoid war or to limit violence, only because we regret death; we regret death because we retain our memories. This is how, as a species, we have learned to survive. Humanity knows what it looks like, in successive generations, when regretful voices of experience gradually remake a bad world into a better one.

Fantasy reigns when reality is too unsatisfying. It may elicit the bad political decisions of an ego-driven chief executive desperate for some sort of victory to hang his legacy on. In war, as we all know from this lifetime, the law is often sidestepped and the truth often compromised. Samuel Johnson, always trenchant, wrote: “Among the calamities of war may be justly numbered the diminution of the love of truth, by the falsehoods which interest dictates and credulity encourages.” If war is the continuation of politics by other means (in the words of Clausewitz), then we have already witnessed truth being butchered in massive chunks by partisan self-interest and voter credulity. Regrets have piled on.

Eighty years ago, President Franklin D. Roosevelt told an audience, “I have seen war. I hate war.” Sixty years ago, President Eisenhower said something else worth remembering, born of experience: “War is the deadly harvest of arrogant and unreasoning minds.” Yet he presided over the unhealthy nuclear arms race of the Cold War years. A sad irony, indeed. It is too much to expect a transformation in human nature, or to avoid war altogether. But it is healthy, and surely a good idea right about now, to promote all the humble reasoners among the scientists and scholars and occasional political officeholders who allow for doubt and shy away from arrogantly declaring certainty.