In Havana there’s a museum so small that it’s easy to mistake for a modest house, so obscure that most Cubans don’t know it exists. It’s no wonder: The Museo Nacional de la Alfabetización isn’t even in most tourist material about Havana, and the history it covers is often left out of the larger narrative about Cuba as a country.

Known in English as the Literacy Museum, the modest space is filled with photographs, film footage, documents, chalk boards and other artifacts from the 1961 literacy campaign, but few visitors.

Its forgotten nature is somewhat at odds with the achievement it documents. Cuba has an average literacy rate of 99.8 percent, according to UNESCO, one of the highest in the world. Further, while most nations’ literacy rate drops significantly across gender lines, Cuba’s barely dips. Even today, Cuba spends the second most of any country on education.

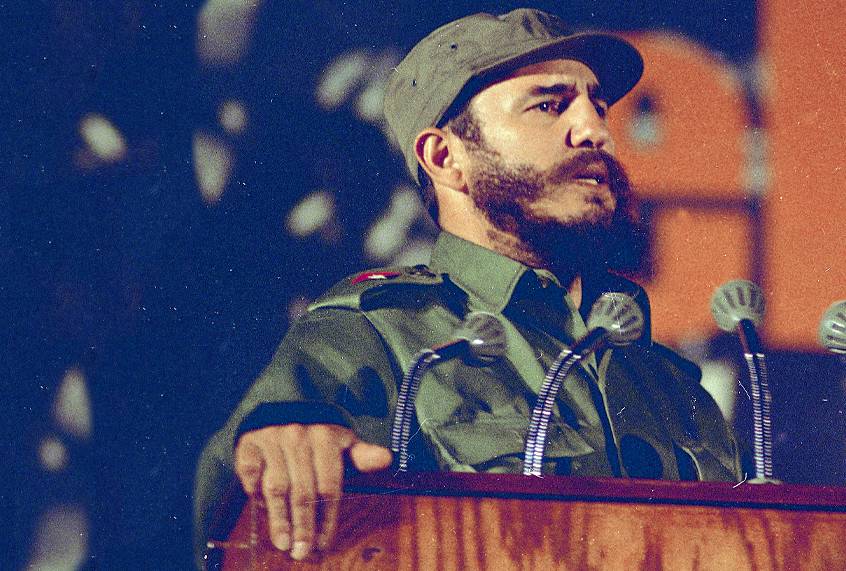

The 1961 campaign, activated two years after the victory of the Cuban Revolution, was dubbed by leader Fidel Castro, “the year of education.” While his tenure as a leader of Cuba was controversial and sometimes destructive, one year after his death, it’s a move worthy of recognition.

Castro targeted the abolition of illiteracy throughout the island and its population of 7.14 million in one year, as for him, education was central to the revolution. “To educate is to give man the keys to the world,” José Martí, the Cuban independence leader famously said.

During Fulgencio Batista’s regime, education was privatized, illiteracy was rampant and disproportionate in rural areas among women, Afro-Cubans and other marginalized populations.

So, Castro put out a call for teachers — half of whom ended up being women and the majority of which were young people — to travel to the countryside of Cuba and educate over 700,000 adults to read and write. Over a quarter of a million teachers joined in, some as young as 15, to educate people as old as 100. According to party numbers, Cuba’s literacy rate rose to 96 percent by the end of the year, and victory was declared.

After the government announced that illiteracy was abolished, the campaign’s teachers and students marched through the streets of Havana, toting giant pencils in triumph.

Norma Guillard, one of the teachers, said in a documentary titled “Maestra” about the celebratory march, “I’ve got many years left, other great things may happen, but to this day, in my recently completed 58 years, I’ve experienced no single thing so enormously powerful,” she said. And of the campaign, Guillard added, “In the history of my life, it is the most important thing that I have done.”

Although the claims that a 96 percent literacy rate was achieved in one year is questionable, given the government’s control of press and information, and 1961 wasn’t without turmoil from Castro’s regime, there is strong third-party evidence from UNESCO that the Cuban method works, nationally and beyond.

Since 1961, the tactics Cuba used have been applied to literacy gaps in more than 30 countries and to educate over 10 million people, including Aboriginal communities in Australia, rural workers in Brazil, people in Mozambique, Venezuela, Angola and Nigeria.

Called “Yo, sí puedo (Yes, I can),” the program targets the teaching of adults who didn’t have access to education as children and never learned to read or write. “The program is uniquely effective because it uses pre-recorded video lessons, adapted for each country, that are delivered by a local facilitator,” Quartz writes. The lessons also go beyond common school subjects and can include health and hygiene, environmental conservation and elderly care.

Global literacy remains an important issue, with 774 million adults unable to read and write, according to 2014 numbers from UNESCO. Studies reveal that those in low-income, rural and otherwise marginalized populations tend to have higher levels of illiteracy. If, as a global community, we want to bring literacy to those 774 million, it’s worth listening to the Cubans about how they achieved what they did and why it worked.

Freedom means different things to different people. For many, the Marxist-Leninist socialism of Cuba isn’t it. Yet, the idea that education is central to liberation is shared by communist and capitalist countries alike. Indeed, the power of literacy was the reason why U.S. slaveholding states deemed teaching slaves to read and write a crime before Emancipation.

Yes, literacy and liberation are far from synonymous, and, no, the ability to read will not solve all of the world’s ills. But certainly, access to the written word is essential for liberation across the globe. That alone makes reconsidering this part of Castro’s complicated legacy worthwhile.