“I’m formerly incarcerated,” and “I spent 10 years in prison for an accident,” Kingsley Rowe told Compass Charter School’s founders during his initial interview for a position there. Rowe was not inexperienced in presenting himself to potential employers, but this was one of the first times Rowe had ever disclosed his prison time without being asked directly.

Rowe, 47, who stands tall at 6’3 but has a gentle and laid back approachability, had a good feeling about this Brooklyn school and the community it nurtured, one where other formerly incarcerated parents were embraced rather than shunned. In the interview, the administrators were apparently unconcerned about Rowe’s criminal history. For the board, the more pressing questions centered on his philosophy of social work and working with children. Compass Charter School, located in Bedford-Stuyvesant, was looking for a behavior intervention specialist for elementary school students, and Rowe seemed a perfect fit.

It took three more interviews, but Rowe was offered the job. He started orientation last August. He was ecstatic. “A dream job” was how Rowe described it. He would be able to work with kids who looked like him, with experiences and challenges he felt he could connect to and guide them through. Rowe remembers telling his wife gleefully, “I could actually work in schools,” a reality he had previously felt impossible, given the violent conviction on his record.

At home in Jackson Heights, Queens, Rowe sinks into the gray suede couch in his basement-level apartment. He wears an army fatigue thermal shirt, dark jeans and boots. He speaks almost as energetically as his two young children, who bounce from his lap to the floor and back again. His tall and wide frame sometimes means he is a human jungle gym for them. Only Rowe’s salt and pepper beard hints at his age.

The white walls in his apartment are bare except for a framed poster of former president Barack Obama and a traditional Jewish marriage contract called a ketubah. Rowe converted to Judaism in 2005. Along the living room’s west wall are two bookshelves with books about Obama, Bob Marley, W.E.B. DuBois, Nelson Mandela and the Dalai Lama. Most striking is a worn, dark-brown wooden desk. The front half is lightened from decades of wrists and elbows hard at work at the computer keyboard. Rowe has owned it for 15 years, and it is here that he wrote his thesis for his master's degree in social work.

* * *

Sharing his criminal history with Compass Charter School signaled a fresh start for Rowe, and with it came a new and welcomed belief that his time in prison no longer fettered him or his ambitions for himself. Under New York City’s Fair Chance Act, enacted in 2015 to ensure employers consider the qualifications of an applicant before their criminal history is disclosed, Rowe is not required to provide the information that he spent time in prison. The law bars employers from asking an applicant about prior convictions until she or he has been conditionally offered a position.

At face value, the law is significant and emblematic of an attitude shift in criminal justice reform. In the 1980s and ‘90s, the ‘tough-on-crime’ posture that overran public policy, resulted in the criminalization of mental health and addiction and was “the standard operating procedure,” said Ronald Day, Associate Vice President at the Fortune Society, an organization dedicated to assisting people with what the criminal justice system calls re-entry. Now, as lawmakers on both sides of the aisle recognize that states cannot afford to continue to imprison this many people — approximately 2.2 million — even in states with notoriously high prison populations like Texas and California, there is some push to reduce them.

But there has been little national attention or effective reform for the plight of people coming home. After extensive stays in prison — especially for violent offenders — another challenge is presented: How do people navigate the limited avenues available to formerly incarcerated individuals in order to survive life after prison?

In New York, a person released from prison, is given $40, a MetroCard, the name of their parole officer and a temporary ID. “Then they’re on their own,” Rachael Hudak, the administrative director of New York University’s Prison Education Program said. “Everything else is a question.”

The Fair Chance Act is supposed to help with this, but it has limitations. The law sets guidelines for when employers can consider criminal history, though it does not change how they evaluate it. And employers can still overturn an offer based on someone’s conviction.

Under New York Correction Law section 753, which has long been on the books and is used to assess a candidate with a criminal conviction, there are eight stipulations for an employer to consider, among the most vague and subjective are if the conviction has what the law calls “bearing” on the job and the interest of the employer in protecting property and safety.

After Rowe was offered the job, he was fingerprinted by the State Department of New York. The Office of School Personnel Review and Accountability (OSPRA) contacted him shortly afterwards. The agency intended to overrule the school decision and was issuing an order of “intent to deny clearance for employment.” If Rowe hoped to convince OSPRA otherwise, he must collect and submit any relevant information about his rehabilitation to prove why he should be allowed to perform the job he was hired to do.

To support his case, Rowe amassed letters of endorsement from reporter Steven Thrasher of the Guardian, Jason Cherkis of HuffPost, his rabbi, nearly a dozen coworkers, five college professors, and detailed letters of support from Compass’ founders and board of trustees.

Rowe also included his certificate of relief from disabilities, which is meant to remove any bar to employment, an order officially terminating his probation, and an in-depth personal statement detailing his crime and his deep remorse. “I had never handled a handgun before that night and have never since,” Rowe wrote. “I was 18 years old then, and today I am a 47-year-old man.”

* * *

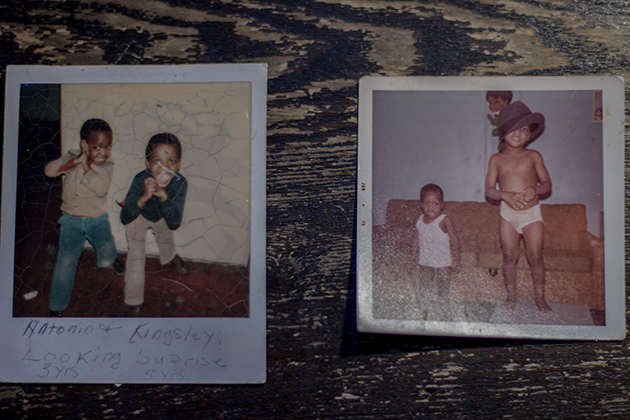

Kingsley Rowe was born in 1970 in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn but moved to South Philadelphia with his mom and four siblings after his parents divorced. Rowe was raised by his mother, Hattie Graham, a stay-at-home mom and part-time nanny, who instilled the power of education. Graham kept a home filled with African history books, comic books, autobiographies, and memoirs of black inventors, activists and leaders.

At eight or nine years old, while doing homework, Rowe was joking around and not taking his writing assignment seriously. His mother demanded he put the pen down and told him that generations before his had died trying to learn how to read and write. “Early on, I really knew about the importance of education,” Rowe said. “But really in the context of the struggle and the history of slavery and how it manifested itself in not allowing African-Americans to be educated.”

In August, 1988, at 18 and right out of high school, Rowe relocated to Washington, D.C. to work as a mail clerk at the FBI. Three months later, while home in Philly for the Thanksgiving holiday, Rowe’s younger brother Antonio brought a handgun into the house.

Antonio told Rowe exactly where the pistol was hidden and then cautioned his older brother not to touch it. Thirty years later, Rowe reflects that perhaps he was drawn to the weapon because he had never seen or touched a gun before. So after he got home from eating Thanksgiving dinner at a friend’s house, Rowe grabbed the Raven MP-25, a cheap, small, semi-automatic pistol, from underneath his brother’s bed and stuffed it into his pocket. He then walked down Hoffman street and met his close friend Raenelle Cerdan. They walked the rest of the way to her aunt’s house.

Rowe and Cerdan had a lot of catching up to do. But after about 20 minutes of small talk, Rowe told Cerdan’s aunt that he had a gun in his pocket. “You really need to take that home. Someone can get hurt,” she warned. Her exact words are still etched in his mind. It was not until that moment, Rowe recalls, that the danger of the situation had dawned on him.

Cerdan said she would walk home with Rowe to return the gun. They started down Emily Street, but Rowe, overwhelmed by anxiety, was desperate to unload the gun immediately. “Come on Kingsley,” Cerdan protested. Having never handled a gun before, he fumbled to remove the clip and the Raven MP-25 fired. Rowe looked up and saw Cerdan falling backwards, shot behind the ear. Out of nowhere, Rowe says, a teenager from the neighborhood grabbed the pistol and took off.

A crowd formed quickly as neighbors streamed out of their homes to see what had happened. Then, things just started to get really loud, Rowe remembers; the sirens of the ambulance and the police, everyone screaming on a small Philadelphia street. Cerdan was alive, but unconscious, and once the paramedics had whisked her away, everything froze. The sound consumed Rowe and he tried to cover his ears.

Rowe’s mom emerged from the crowd and he ran to her and collapsed in her arms. “It was an accident,” he cried out. The police handcuffed Rowe and placed him in the back of the car. Rowe’s mom continued to try to calm him through the police car window. “It’s going to be OK,” she told him.

Cerdan, 20, died in the hospital 15 days later, and Rowe was charged with third degree murder and for possession of a gun. His case went to trial in 1989.

Rowe was in a complete daze, trying to wrap his mind around taking a life. He felt and plead guilty, and the judge sentenced him to a minimum term of eight to 20 years. Already in jail, the state truck picked Rowe up and took him to prison at Smithfield State Correctional Institution in Huntingdon, Pennsylvania.

Michael Childs, Rowe’s cellmate from 1992-1994, recalls his first impression of Rowe. One day, he walked into the TV room and saw Rowe and about three other guys talking about social justice. While generally everyone was in agreement, he said, Rowe stood out.

“He sounded more like a professor,” Childs said, and he thought “Who is this guy? He sounds like he should be at Harvard.”

In addition to Childs admiring Rowe’s intellectual approach to the conversation, he was impressed by the fact that everything Rowe said was accompanied by a smile. “He was totally the opposite of whatever was on paper about why he was there,” Childs said.

In 1992, Rowe started taking college courses through Saint Francis College (now University) in prison. Two years later, President Bill Clinton signed the crime bill taking away Pell grants for prisoners, which supported prison education. Saint Francis decided that they would allow inmates already enrolled in the program the opportunity to complete their Associate’s degree. “I was a part of the last cohort,” Rowe said. “I was really lucky in that respect.”

On March 28, 1999 — at 29 years old and after a decade in prison — Rowe was released. He had $100, a change of clothes, 300 books and his freedom. He was a nervous wreck. The prison bus took him to the Amtrak in Huntingdon, Pennsylvania. When the train stopped briefly in Philadelphia, his family met him on the platform. It was the first time he had seen or talked to his younger brother Antonio since Rowe picked up the gun he brought home.

Rowe continued on to New York City, but, overwhelmed “by being free,” he felt compelled to reveal himself, telling perfect strangers that he’d just been released from prison. “Everyone doesn’t need to know that,” his father advised him when he met him in Penn Station. It was a suggestion Rowe would take to heart. The next morning Rowe woke up crying. He had no idea what to do. “For 10 years, I had a schedule, a regimen,” he said, “and then it wasn’t there anymore.”

* * *

“I don’t think anything really sticks to you like prison does,” NYU Prison Education professor Gabe Heller said. “To go through that experience of being incarcerated is a very heavy, painful experience, and then to come out and to still feel like you have that shadow hanging over you, there’s a lot of shame.”

After three months of freedom, Rowe had transferred his straight A transcript from Saint Francis College to New York University. He worked full time at Macy’s and went to school full time to finish his BA.

Rowe’s reintegration came not from talking about his incarceration but by suppressing it. “What I said to myself was, I wasn’t going to give anyone an opportunity to discriminate against me based on my conviction, so I lied about everything,” Rowe said of his prison background. (Lying about a prison record is against the law.) During job interviews, Rowe would tell employers that he went back home to live with his mom, traveled overseas, participated in a fellowship, lacked focused, to explain the gaps in his work history.

In 2004, Rowe began working towards a Master’s in social work at NYU. After graduation in 2006, he worked as a social worker at Kingsbrook Jewish Medical Center hospital in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, in affordable housing with Pratt Community Council (now IMPACCT Brooklyn), as a children’s therapist in Saint Luke’s Hospital, as a senior social worker with The Center for Alternative Sentencing and Employment Services (CASES), and with Gay Men’s Health Crisis.

Heather Herz, a co-worker at Saint Luke’s, said, especially for the children they worked with, many who suffered from behavior disorders and trauma, “it can be really difficult for the kids to open up and feel comfortable and share their story, and I think Kingsley came through with an authenticity that the kids can immediately pick up on.” She said, “they really looked up to him.” Janet Taylor, a co-worker of Rowe’s at CASES, described him as “tireless” and courageous as an advocate.

Nonetheless, when it came to his own past, Rowe was in complete denial. “I had convinced myself that I had never been to jail,” he said. “That’s how deep it was.”

Rowe’s background was only checked one time during the decade he kept his prison time hidden. After years of working at Saint Luke’s, every employee was fingerprinted. When the results came back, Rowe was informed that either he could resign or they would tell his employer of his criminal background.

Rowe resigned. He was not sure they cared if he was formerly incarcerated or were just protecting themselves from exposure, but the potential shame was enough for him to bow out silently. “You feel people are judging you,” Rowe said. “Sometimes you don’t want to be that guy . . . I’m black and I fit their stereotype by saying ‘I have a criminal record.’ I wasn’t about to give anyone no extra ammunition.”

“Employment issues, access to healthcare and education. Every human right is hinged with this ‘scarlet letter,’” Julia Mendoza, a professor with NYU’s Prison Education Program, said of the stain attached to incarceration. “There’s really no area of your life that it doesn’t seriously affect.”

The myth, Rowe explained, is that you’re supposed to “make good on your freedom” and become a productive member of society, but for people who come out of prison with no education or resources, “You hear all the time ‘pull yourself up by your bootstraps,’” Rowe said. “Well a lot of people that are formerly incarcerated don’t even have boots.” The transition from such a traumatic environment alone can feel daunting, never mind the upward and often lonely battle of reintegration.

* * *

In 2013, after 14 years free, Rowe decided to share his story. The Huffington Post (now HuffPost) was looking for people to speak about their experiences with gun violence, and Rowe called in and spoke to reporter Jason Cherkis, the same journalist who wrote a letter for him in support to OSPRA. On May 5, the story, “Unintentional Shooting Kills Friend, Torments Shooter: ‘Why Did I Pick Up The Gun?’” published, and Rowe shared it to his Facebook.

The post got 22 comments. “I can’t believe I had no idea about this huge part of your past,” one friend wrote. “I’m so sorry you’ve had to carry this burden for so many years. You are such a gentle man.”

This new found acceptance of his journey was further validated when Rowe applied to NYU’s Prison Education Program to work as a re-entry coordinator. He described the hiring process as “dignified,” one where his criminal history was asked only after he was offered the position.

Ronald Day from the Fortune Society argues that New York has far more progressive policies protecting former felons than most states, but the vagueness in language under Correction Law section 752, specifically in what outlines the basis for employers to deny formerly incarcerated individuals, leaves much room for interpretation. Sally Friedman from the Legal Action Center, a nonprofit that fights discrimination against people with addiction, HIV and criminal records, acknowledged that even though employers are supposed to weigh the eight factors specified in Correction Law section 753, “it's very tempting for employers to hone in on 'what did you do' and really not look at anything else.”

“It would be dishonest to say people can’t get jobs,” Day said, “but it’s a struggle.” As far as second chances, he added, “it seems to me like they mean if you’ve been convicted of a nonviolent offense.” It is a discrepancy that black people experience more than any other cohort. As Michelle Alexander writes in “The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness,” “Black men convicted of felonies are the least likely to receive job offers of any demographic group.”

* * *

On September 13, 2017, Rowe received a second letter from the Office of School Personnel Review and Accountability. His application for employment clearance was denied. They claimed that despite the “over 70 pages” of supporting documents, there was a “direct relationship” between his conviction and the position he was offered, and to clear him would “involve an unreasonable risk to property or to the safety of specific individuals or the general public.” At 19, the attorney at OSPRA found him to be a fully mature adult at the age of his original conviction.

While the investigative unit listed the factors they considered when making their decision, they noticeably left out the following variable: “The time which has elapsed since the occurrence of the criminal offense or offenses.” When probed for clarification, a department spokesperson for NYS Education Department said: “We never comment on individual cases.”

Bill Otis, a Georgetown law professor and conservative federal prosecutor, said that employers have to think critically about hiring formerly incarcerated individuals because employers risk being sued for the actions of their employees. “It’s not discrimination, it’s a legitimate thing that an employer has to think about.” Otis said, “We have a very high recidivism rate, which indicates once a person has engaged in crime to the point where he gets a prison sentence, as a statistical matter, the chances are low that he is going to lead a crime-free life after that.” But he added, “Murder is the offense which there is the least recidivism.”

As a father of two himself, Rowe acknowledges that the safety of children is paramount, but he still finds it hard to grapple with the reality that after 20 years of freedom, completing 13 years on parole with no violations, and with two degrees from NYU, he still is “being discriminated against for a crime that I was guilty of 30 years ago.”

“None of us are the same person that we were at age 19,” Brandon Garrett, law professor at University of Virginia said. “But it’s like prison is this ‘other,’ those aren’t people like us.”

In a system dangerously compromised by wrongful convictions, where mental health, homelessness and drug addiction are often treated as criminal, and where black communities are overly policed and incarcerated, it can be difficult to point to any moments of success. But Rowe’s story is the essence of what we say prison is supposed to be about. He made a mistake. He owned up to his crime, did his time and after his release, he educated and empowered himself and then committed himself to doing the same for an array of marginalized communities ever since.

If the system cannot accommodate Rowe and he is still being denied employment and the tools needed to survive after prison, he wonders, what chance is there for the hundreds of thousands of men and women coming out of prison each year and looking to start anew?

“For many people, when you hear prison, you hear offender, you hear felony,” former co-worker and psychiatrist Janet Taylor said. “It just conjures up in their minds this image of someone who should never see the light of day.”

Rowe has appealed OSPRA's denial, but it could take up to two years for a final decision, and, in Rowe’s words, this job is now. He is looking for other work, trying to stay on top of his massive student debt, but he admits that he feels “stunted.”

“Frankly, I was disappointed with the outcome,” Taylor said. “In our society, where we have so many parents who are criminal justice involved, and then been labeled as felons, what message are we sending?”

Rowe knows the fight goes far beyond his individual case. It comes down to whether, as a nation, for people branded as violent offenders, if “second chances” are not just written into law, but possible. He acknowledges it is something our country has yet to prove.

“No matter how successful you are, and no matter how much education you have,” Rowe said, “people are still going to look at you as a criminal. That’s the nature of punishment here in America.” But he wants to know: “How much punishment is enough?”

Shares