All accounts of “Exile on Main Street” are heavy on the dark side, not just the relatively minor inconveniences that came with the recording. In a 1995 interview, Jagger looked back, not too fondly:

(We were) just winging it. Staying up all night . . . Stoned on something; one thing or another. So I don’t think it was particularly pleasant. I didn’t have a very good time. It was this communal thing where you don’t know whether you’re recording or living or having dinner; you don’t know when you’re gonna play, when you’re gonna sing—very difficult. Too many hangers-on. I went with the flow, and the album got made. These things have a certain energy, and there’s a certain flow to it, and it got impossible. Everyone was so out of it. And the engineers, the producers—all the people that were supposed to be organized—were more disorganized than anybody.

And Bill Wyman explained:

. . . We worked every night, from 8pm to 3am, until the end of June (1971), although not everyone turned up each night. This was, for me, one of the major frustrations of this whole period. For our previous two albums we had worked well, been pretty disciplined and listened to producer Jimmy Miller. At Nellcôte things were different and it took me a while to understand why.

Wyman recounts that further distractions came when “recording in Keith’s basement had not turned out to be a guarantee of his presence. Sometimes he wouldn’t come downstairs at all.” And he didn’t enjoy the “dull and boring” jam sessions that constituted most of the initial nights of recording. Keith and Anita’s lifestyle “was becoming increasingly chaotic” and drugs were taking their toll on Keith and subsequently on the recording process. Possibly in retaliation, Mick would often not show up; perhaps being a newlywed was a further distraction, his and Bianca’s wedding having just taken place on May 12. Then there was their announcement, a month later, that Bianca was expecting a baby. The two lovebirds were often jetting off for holidays in the middle of the time period set aside for recording. The tit-for-tat kept on escalating.

And even when the recording was going well, it was disorganized. Bill Wyman recalled, negatively, that Andy Johns would often be trying to record overdubs in the basement kitchen while people, dogs, and children, ate and made noise in the same room: “I remember Gram Parsons sitting in the kitchen in France one day, while we were overdubbing vocals or something. It was crazy. Someone is sitting in the kitchen overdubbing guitar and people are sitting at the table, talking, knives, forks, plates clanking. . . . It was like one of those 1960s party records in which everyone felt they should be involved.”

But the main negative that he points to in the making of “Exile” was the increasing reliance on hard drugs. “Whatever people tell you about the creative relationship between hard drugs and making of rock & roll records, forget it,” he writes. “They are much more a hindrance than a help.” Wyman notes that Mick was very concerned about Keith and that the hard drugs were dividing the “Exile” personnel into camps—those who abused, and those who enjoyed in relative moderation or abstained altogether. The latter were often not included in the recording process and were made to feel alienated. Wyman showed up on one occasion to discover two of his bass parts re-recorded by Keith. And the new parts, Bill felt, were inferior to those he’d recorded.

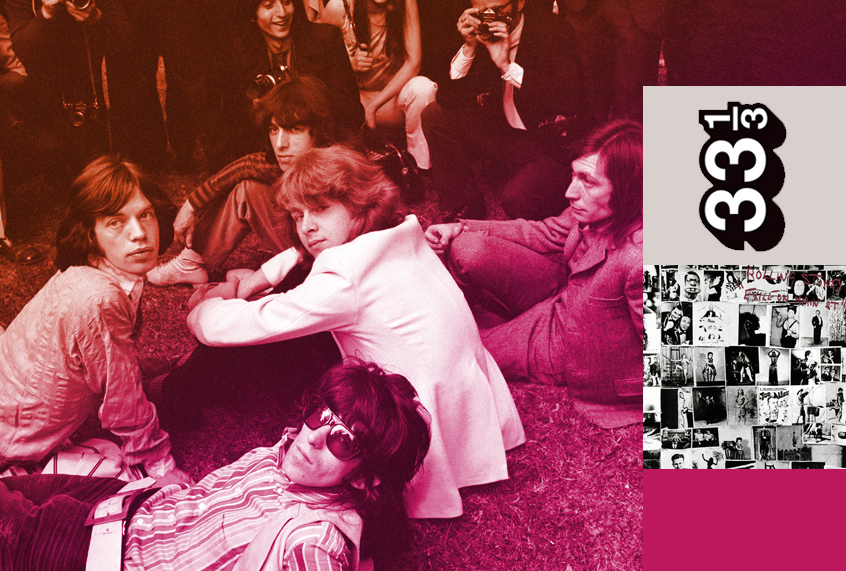

But for all the problems and obstacles, the Stones could ultimately sell the rock & roll myth because they lived it. The lived all of it, the positives and the negatives. They even succeed at transforming the awful side of the lifestyle into a myth of decadent glamour. Not that Keith set out to, but is it any wonder his image influenced so many musicians to spike up their hair, take up smack, and cultivate their skin-and-bones physiques? I never even tried to pull it off, but always secretly wished I could. Others looked lame and ultimately died trying, including Johnny Thunders, never mind third- and fourth-generation wannabes like Guns N’ Roses or the Black Crowes. That’s why Elvis Costello’s rise was such a pivotal moment for dweebs like me. (To paraphrase the quote attributed to David Lee Roth: most critics love Elvis Costello because most critics look like Elvis Costello.) But I still had a poster of Jagger and Richards up on my wall, at which my father would shake his head and mumble out of the corner of his mouth, “your heroes, eh?” The Glimmer Twins knew the attraction of the down and dirty street, the drugged and dangerous. “I gave you the diamonds / you gave me disease,” Jagger scrawled in the album jacket. Coinciding with a famous Rolling Stone cover shot and interview with Keith Richards, the whole of “Exile on Main St.” offers up the sleazy glamour referred to now as junkie chic. The Stones were cementing their image and in turn, defining the prototypical image of a 1970s rock & roll band.

And much of that impression hinged around Keith’s increasing prominence in the band’s public image, a trend that had started gradually back around Brian Jones’ death in 1969. In many ways, Exile is considered Keith’s record: recorded at his house, more or less on his schedule, vocals down in the mix, guitars up. All accounts talk about long leisurely dinners set for double-digit guests, lasting until roughly midnight, when a vampiric Keith would beckon the musicians and crew to work. He would often disappear again for hours while, according to him, he put son Marlon to bed. Finally, he would reemerge in the wee hours ready to work again, by which point the others had usually drifted off or disappeared. But the sessions would usually last until dawn, players emerging out of the dank, dark, hot cellar into the morning daylight of the Riviera. “The days just ran into days and we didn’t get any sleep,” remembered Mick Taylor in Mojo. “I remember staggering out of the basement at six in the morning and the sunlight hitting my eyes and driving home.” They were ghoulish outsiders, nocturnal vampires, exiles from the daylight.