Raising money for a high-profile political race is not the panacea it once was in the early days of televised campaign advertising. Just ask former Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton, who outraised future-president Donald Trump by a margin of $564 million to $333 million — or Jon Ossoff, the failed Georgia Democratic congressional candidate who brought in $23 million more than his opponent but still came up short.

But most political races do not attract much public notice. That’s especially true at the municipal level, where both voting and contribution rates are far lower. In such races, advertising is even more important because people will not support candidates they do not know. (That was even true of then-senator Barack Obama, who actually trailed Clinton throughout most of 2007 among black voters.)

For local races, the net effect of having such low levels of participation is that a small number of wealthy organizations and individuals are often able to skew politics in their direction. Republicans certainly proved this through the wildly successful REDMAP program, which enabled them to effectively purchase control of hundreds of state legislature seats that Democrats mostly ignored during the politically disastrous Obama years.

At the municipal level, where attracting donations and attention is even more difficult, government employees have managed to attain significant clout thanks to their well-funded treasuries and willingness to bloc-vote.

At the same time, local races (even in highly progressive metro areas) are often influenced by out-of-town real estate developers and others who are more interested in tax subsidies than in improving services for communities. People who don’t have such connections very often get left out, particularly would-be candidates who are not wealthy or not already involved in government.

“We did some research and we saw that a large portion of the money coming into campaign coffers was from real estate developers, many of whom were not even residents,” Val Ervin, a senior adviser at the Working Families Party, told Salon in an interview.

In an effort to bring new candidates and re-energize local politics, the WFP has been working to promote the public funding of elections in municipal races. The group’s efforts succeeded last week when the city council in Washington, D.C., voted unanimously to establish a new public campaign finance program.

The proposed Washington system would require candidates to raise a minimum amount of money, after which they will receive a base amount and then five-to-one matching funds.

“The base grant is a lump sum of money, and it is key to ensuring that candidates who may not be individually wealthy or well-connected have setup money to begin a viable campaign,” said Nolan Treadway, the communications director for D.C. Councilmember Kenyan McDuffie.

In addition to making it easier for lesser-known and under-financed candidates to have a chance, the much lower limits (a maximum donation of $200 per person) and the matching funds are designed to help candidates get out into the community and interact with voters.

“I think everybody acknowledges that campaigns cost money, but when a candidate has to spend the majority of their time fundraising, sitting in a room calling people who can write big checks instead of talking to residents, then they’re not spending their time where they need to,” Councilmember Charles Allen said. “I would much rather spend that time talking with residents.”

Although this proposal was passed unanimously by the council, Washington Mayor Muriel Bowser has indicated that she sees the public funding proposal as a waste of money. Bowser has not commented on the proposal since it passed the council, but her representatives referred The Washington Post to her earlier remarks that the idea would result in less money for “pressing needs for residents.”

While the estimated $5 million that the program would cost would have to come from the city’s general operating fund, the amount is minimal compared to D.C.’s $13.8 billion annual budget.

The fact that Bowser might be ambivalent or hostile toward the idea is not exactly a surprise. She was able to raise $3.6 million during her 2014 mayoral run and faces no prominent challengers in her 2018 re-election bid.

Bowser’s success at raising money reveals a potential flaw of the system, since candidates are not obligated to use public funds. So a publicly funded challenger to Bowser would only receive a $150,000 base grant, nowhere near what would be needed to mount a full-scale campaign.

The proposed D.C. law shares similarities with laws enacted by Wisconsin and Minnesota that only provide partial funding to candidates. In contrast, systems implemented in Arizona, Maine and Connecticut have been billed as “clean election” plans because they only require candidates to raise a small amount via low-dollar donations in order to qualify for a much larger amount from the government. Candidates who opt-in to the system cannot receive private contributions after doing so.

Since public funding of elections is still relatively new — except at the level of the presidential general election, where it’s been in place since 1976 — political scientists have not yet come to a consensus on its effects.

A few trends have emerged from the nascent research, however. According to Michael G. Miller of Barnard College, while partial public funding can encourage new candidates, it appears to have no effect during general elections, compared to states that have traditional private donation systems. Miller’s research on different states also found that public matching systems can easily be manipulated by incumbent politicians.

Another paper written by Andrew B. Hall, now a professor of political science at Stanford, shows that public funding of elections seems to make it harder for incumbents to win re-election. According to Hall, “public funding decreases the electoral incumbency advantage by as much as 8.19 percentage points.”

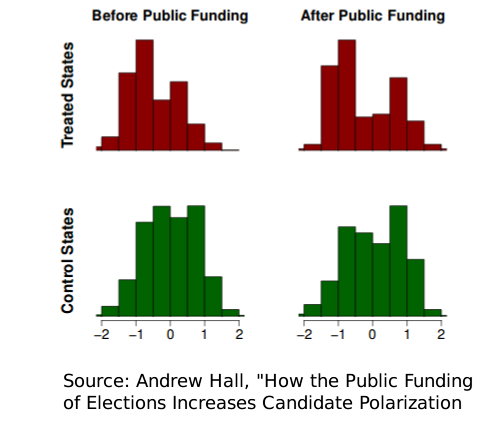

Hall’s study, which does not distinguish between partial and full public funding, also found that the ideological position of state legislators also varied under public financing systems. Localities that allow candidates to have their campaigns funded by the public were found to shift ideologically toward the left, but with the curious side effect of producing a small number of far-right conservative candidates.

It’s too early to say whether public financing of elections will have a major impact on the ailing state of our democracy, but it seems clear that various cities, counties and states are eager to find out.