A dozen Senate Democrats are threatening to torpedo any semblance of a unified economic message from the opposition party ahead of this fall’s midterm elections, trampling over the fiercest progressive voices in the party to do so.

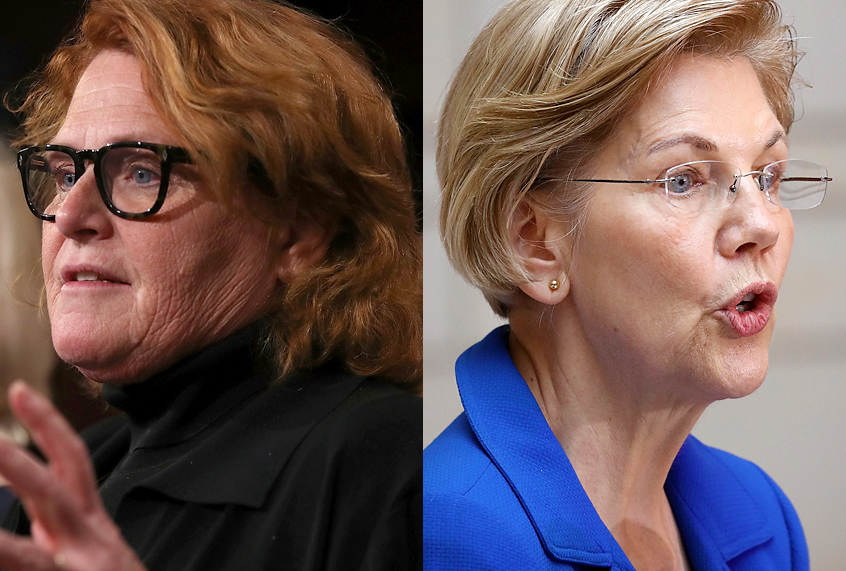

“I don’t think a bill like that is good for anybody in America,” warned Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., on NBC’s “Meet the Press” on Sunday, referring to a Republican effort to roll back rules meant to prevent a repeat of the financial crisis that struck 10 years ago. Warren is the Senate’s strongest consumer protection advocate, elected in 2012 in a crusade against big Wall Street bailouts.

Democrats in the Senate joined the Republican majority to end debate on an amendment to a broad financial deregulation package late Monday, advancing the most significant revision of banking rules since the historic 2010 Dodd-Frank law.

Even as interest rates have remained extremely low and banks have posted record profits, Republicans, along with some centrist Democrats, have long argued that rules enacted after the 2008 financial collapse went too far, stifling smaller banks.

“Too big to fail,” proponents of the deregulation bill argue, has left community banks “too small to succeed.”

Under the Obama-era regulations, financial institutions with at least $50 billion in assets have to undergo frequent “stress testing” by the Federal Reserve to determine whether they have enough cash on hand to withstand a sudden shock. The new bill backed by several Senate Democrats would require fewer banks to undergo such scrutiny, raising the minimum criteria of big banks to $250 billion in assets, while changing the annual stress tests to unspecified “periodic” tests to be conducted by Trump-appointed regulators.

Sen. Mark Warner, D-Va., a co-sponsor of the bill, said it aims to roll back “unnecessary and burdensome regulations on credit unions and small community banks.”

That sounds reasonable, even worthy. But, in fact, loan balances at community banks rose nearly 8 percent in 2017, and this bill’s definition of “community bank” is so generous it will include financial institution that have branches in more than one state.

As written when 17 Democratic members of the Senate Banking Committee voted last week to advance the bill, major financial institutions including American Express, SunTrust, Citigroup, Deutsche Bank and Barclays would no longer be subject to the most rigorous checks. The Congressional Budget Office warned that the bill relaxing regulations on 25 of the 38 biggest banks in the country would make financial firms with assets between $100 billion and $250 billion more likely to fail.

On Monday, the Senate added an amendment specifying that foreign banks with U.S. holdings of less than $250 billion but more than that overseas would still be subject to closer oversight. The Senate is likely to approve the measure by Wednesday.

The new law would also remove the ability of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (spearheaded by Warren) to monitor whether applicants with the same credit score were being offered or denied mortgage loans based on race. The banking industry has claimed that apparent discrimination is due to disparities in credit scores, not racial redlining. From The Washington Post:

Congress had charged the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, an independent watchdog agency formed after the financial crisis, with collecting, analyzing and publishing the data. But White House budget director Mick Mulvaney, named the CFPB’s acting director last November, said the agency plans to reconsider the new requirements, and that banks would not be penalized for data collection errors in 2018. He also stripped the bureau’s fair-lending office of its enforcement powers.

The collection of this data can hardly be considered onerous. All a bank has to do is run a program pulling out the information it has already collected from applicants. The proposed legislation would exempt 85 percent of banks and credit unions from such reporting, according to a CFPB analysis of 2013 data. It isn’t hard to see why this bill remains remarkably unpopular with Democrats’ progressive base, as the Huffington Post’s Zach Carter recently noted:

The AFL-CIO, the consumer watchdogs at Public Citizen, the establishment think-tankers at the Center for American Progress, the wonk-activists at Indivisible and the banking experts at Americans for Financial Reform have all weighed in against the legislation, citing harms to consumers and risks to financial stability. The National Fair Housing Alliance, the National Housing Law Project and the National Urban League have all specifically criticized the provision on anti-discrimination data.

So why would Senate Democrats, who stayed unified in their opposition to the Republican tax-cut bill just a few months earlier, support such an obviously flawed bill opposed by large swaths of the base?

“We’re seeing way, way, way too many banks being eaten up by bigger banks,” explained Sen. Jon Tester, D-Mont., one of the most vulnerable Democrats in this year’s midterm elections. “If this continues, I don’t think we can expect the Wall Street banks to be serving places like Montana.”

His fellow centrist lawmakers who helped author the bill — including Sen. Heidi Heitkamp of North Dakota, Sen. Joe Donnelly of Indiana and Sen. Claire McCaskill of Missouri (all up for re-election this year in states won by Donald Trump) — have frequently echoed Tester’s claim that this legislation will help small banks lend more easily to local businesses on “Main Street.” It should be noted that Heitkamp, Donnelly and Tester are the top three recipients of campaign contributions from commercial banks in the 2018 cycle, according to the Center for Responsive Politics data.

Red-state Democrats are also eager to present themselves as the bipartisan veneer atop the stalled Trump agenda. “I hope that our bipartisan work can rub off on the rest of Congress so we can break through the partisan gridlock that has plagued Washington for too long,” Tester recently told The Wall Street Journal. This might be a smart strategy in states Trump won by double digits. (If any of those four senators loses this fall, Democrats’ hopes of winning a Senate majority are essentially gone.) But this banking bill isn’t the hill to die on for Democrats desperate to prove their bipartisan bonafides. House Republicans, led by objections from the ultra-conservative House Freedom Caucus, will protest amendments to tighten regulations in the Senate version, and Democrats in the Senate have shown no willingness to use their potential support as leverage to demand deeper concessions. (While remaining opposed to the bill, Warren offered 17 amendments, including imposing penalties on credit bureaus that were hacked and preventing employers from asking job applicants for credit reports.)

Turning Warren into the Nancy Pelosi of the Senate — meaning the progressive punching bag from a blue state — while supporting a bill that has few obvious selling points for a small constituency, is not likely to be the kind of politics that will rescue vulnerable Democrats this fall. Democrats must indeed concede that the economy has remained strong under Trump’s watch and must be willing to make considered concessions — perhaps on Trump’s proposed steel and aluminum tariffs, rather than on corporate tax cuts or banking deregulation.

“The legislation we’re considering today has been portrayed as modest — as something just helping community banks, credit unions and our regional lenders,” said Sen. Sherrod Brown of Ohio, on the Senate floor Friday. “Unfortunately that’s not what this bill is.” Brown, along with two other Democrats up for re-election in states won by Trump — Sen. Bob Casey of Pennsylvania and Sen. Tammy Baldwin of Wisconsin, has been as forceful in his condemnation of the bill as the party’s more progressive potential 2020 presidential contenders. So Brown and Warren find themselves on the same side as The Wall Street Journal’s editorial board, which called out the bill as “a sneaky reduction in capital rules,” while 2016 vice presidential candidate Sen. Tim Kaine, D-Va., a former fair-housing lawyer, finds himself siding with the Republican majority. Such is the bizarro-world of bipartisanship in the Trump era — and there goes any unified Democratic message on the economy.