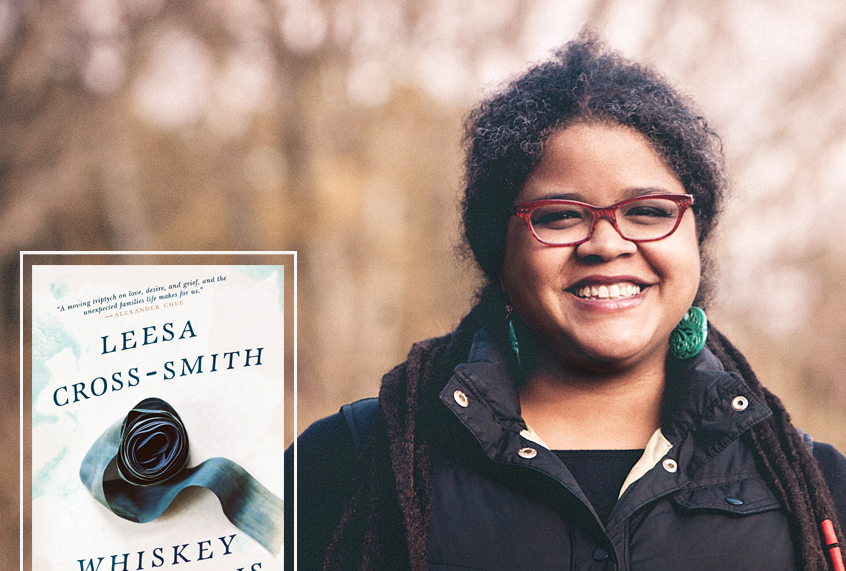

Leesa Cross-Smith’s debut novel “Whiskey & Ribbons” (Hub City Press), which came out earlier this month, was one of the season’s most anticipated books, judging by the wave of advance positive buzz in outlets ranging from Entertainment Weekly and Southern Living to Chicago Review of Books and Refinery29. Cross-Smith, who Roxane Gay has called “a consummate storyteller,” has earned every rave. Set in Louisville, “Whiskey & Ribbons” tells the story, in three braided voices and timelines, of ballet dancer Evangeline, who becomes a widow and a mother pretty much at the same time when her husband Eamon, a police officer, is shot and killed in the line of duty as she approaches her due date. Eamon’s adopted brother and best friend Dalton, a classically trained pianist and bike shop owner, steps in to help Evangeline raise baby Noah while grappling with his own family-of-origin issues.

In their post-Eamon life, over one long snowed-in weekend, Dalton and Evangeline try to untangle their complicated dance of desire and grief, to figure out what a shared future could look like with their other half missing. Music is one of Cross-Smith’s passions — fans of Sturgill Simpson will recognize her as the author of this amazing Oxford American cover story from last fall — and “Whiskey & Ribbons” is told in the shape of a fugue, which pulls double duty as a shaping metaphor.

With her husband Loren, Cross-Smith founded and edits the literary journal WhiskeyPaper. Her first book, the 2014 short story collection “Every Kiss a War,” was nominated for the PEN Open Book Award after being a finalist for both the Flannery O’Connor Award for Short Fiction and the Iowa Short Fiction Award. She is also a baseball fan and — Jonathan Franzen, take note — a birder, both consummate novelist pursuits that require a certain level of comfort with slow action, meticulous note-taking and occasional brushes with magic.

For a while, the debate between “MFA or NYC?” delineated the two acceptable environments in which emerging writers could expect to build a career. Cross-Smith, who calls herself a “Southern, sentimental homemaker and writer from Kentucky,” took a pass on both. “I couldn’t afford an MFA program and wasn’t willing to go into debt to do it,” she told me. “So I made my own path by writing, submitting, reading, reading and writing, and writing and writing some more.”

“I have an English degree and took a lot of creative writing classes in college, but after that I just started writing and reading. I’d read essays about ‘stealing’ MFAs because they made me laugh,” she added. “I researched where writers I admired were getting published. I spent a lot of time reading literary magazines.”

Salon caught up with Cross-Smith during her book tour to talk about writing a non-political novel, “bad” Christian art, first novels and more.

I’m always interested in how first novels come into the world. Can you talk a little about the lifespan of the manuscript before it had a publication date?

Although I got an idea to write a story/play/screenplay about one woman loving two men back in 2000/2001, I didn’t get serious about making it a real thing until around 2010 when I wrote the short story. I couldn’t stop thinking about it, kept returning to it, wrote three or four books in between to avoid trying to figure out how to structure it until around Spring 2016 when I finally finished it.

The book’s action revolves around grief and how to go on living after loss. But it’s also a profoundly uplifting story. How important was achieving that balance to you?

Super-important! I couldn’t and wouldn’t have written it if I hadn’t been able to find a way to infuse it with some sort of lift and hope. And I so admire people who keep on keeping on when the world and their circumstances shatter them completely. I wanted to write a story that dealt with people working through their grief in a real way, people who are holding on even when it would make perfect sense for them to give up or at least want to give up.

Love triangle stories — even gentle ones like this one — can be controversial among fans. Is there a #TeamEamon out there arguing that Dalton and Evangeline should remain platonic out of respect for his memory? Is anyone pulling for Cassidy, Dalton’s bike shop crush, in this story? Did you always know when you were writing how their story would end?

I’m not sure about the #TeamEamon thing but my guess would be, probably? And people have mentioned to me how much they love Cassidy, which is sweet. I love her too! My dad really loves Cassidy, which is so cute. I did always know how their story would end, but I didn’t know every little bit about how I was going to get there.

Something that really stood out for me about your characters is the role religion plays in their lives. Evangeline and Eamon meet at her church. God is an active presence in their lives, and yet not a source of trauma. And I think that’s rare in literary fiction. Can you talk a little about the role Christianity, church and religion play in the lives of your characters, and why it was important for them to have a foundation of faith?

Thank you, because I consider this a high compliment! I speak and write often about growing up a PK — a Preacher’s Kid. My dad is a Southern Baptist preacher and my faith has always been a bit easy for me. I love Jesus and feel very confident in saying that boldly because it’s true. And I reject the idea that “Christian” art or music or books have to be bad. There’s that connotation because so often, that stuff is so bad! But the thing is . . . it should be good! It should be the best. And while I won’t say my book is a “Christian” book because that can mean so many things, and so many of those things are wrong, but there are Christians in my book, and I’m a Christian writing the book.

I wanted my characters to be as real as possible about everything and that includes their faith. Evi prays and curses. She easily expresses both her frustration at feeling abandoned by God and the hope of one day seeing Eamon again in Heaven. Eamon and Dalton are good, flawed men who grapple with sin and what being a “good” man means. Writing about Christian characters living their lives, their struggles and hopes in a non-political way felt a bit radical and was important to me to put on the page because like you said, it’s sometimes rare in literary fiction. Everyone’s a cynic and Christianity is easily made fun of or scoffed at because of the sometimes ridiculousness of “American” Christianity and because people are people and there’s so much hypocrisy in the world. But none of that changes who Jesus says He is. And I reject all of that negativity anyway. So do my characters.

This is a story set in Kentucky, about black and biracial main characters, built around the death of a police officer, at a time when gun violence, race and the role of police in cities are all highly charged subjects. But “Whiskey & Ribbons” is a personal story, a family story, a love story. It’s not, at least in any traditional sense, a political narrative. Have you had to talk about that choice a lot?

And on a related note, are there expectations that people have for your book, or for you as an author, that you find surprising, or frustrating, or are even relieved by?

I have ended up talking about the fact the the book isn’t a political book quite often and I don’t mind it! It’s not a political book. I’ve had several people tell me they were relieved to discover that. There are a lot of brilliant writers and activists telling those stories and telling them well. That’s not what I’m doing.

As for expectations, there’s always the idea of whether my book can be white enough for white people or black enough for black people, but I also reject that and those pressures. Black writers don’t need permission to write books that don’t focus on race and neither do black women. White writers aren’t constantly asked about their whiteness; men aren’t usually asked about their maleness. I’m pretty hardcore about rejecting those things. I just won’t entertain them. I write what I want to write, how I want to write it. I’m not waiting around for people to catch up. Who has the time?

Much of the way the state’s literary tradition is perceived, both outside of the region and within, is rural, but “Whiskey & Ribbons” is a Louisville story, a city story. Do you feel like a Kentucky writer?

I do feel like a Kentucky writer, simply because I’m from Kentucky. Born and raised. This is home. I never considered setting this story anywhere else. Setting it in Louisville was important to me because I don’t get to read books set in Louisville very often. There are books that mention Louisville and Actor’s Theatre or Churchill Downs, etc, but I wanted to keep the story here because I’m here. And some of my favorite writers, like C.E. Morgan, Crystal Wilkinson, Silas House, they’re Kentucky writers. I’m drawn to Kentucky writers because they feel like home — the cities, the farms, everything in between. All of it.

One thing I love about “Whiskey & Ribbons” is the role music plays in the characters’ lives. They feel it deeply, and Dalton plays piano and Evangeline dances. Did you have a writing soundtrack?

I did! There’s a lot of yacht rock on it. A lot of Phil Collins, Sade, Otis Redding. Power ballads. Grateful Dead. Marshall Tucker Band. Fleetwood Mac. A lot of ballet warm-ups and piano music. Mozart, Chopin, Debussy, Bach. My soundtrack is about 15 hours long!

Music, like sports, is a frequent subject in your work. What were you not an expert in that you had to learn about to write Dalton, Eamon and Evangeline?

I had to learn things about police work for Eamon. I had to learn about fugues for the structure of the novel and about classical piano pieces for Dalton. I had to learn a bit about bikes because Dalton owns a bike shop. I also had to remember what it was like to have a six-month-old baby for Evangeline because my kids are so much older now that I’d practically forgotten!

The title of the book, “Whiskey & Ribbons,” refers to a toast the characters make. Does that have an origin outside of the book or is it original to this story?

I chose “whiskey and ribbons” simply because I like the words. And I liked thinking about men as the whiskey and women as the ribbons. Originally it wasn’t a toast, they were just words Eamon liked and would link together, but then my sweet girlfriend Sarah suggested that it should be a toast, something Eamon would say when they drank whiskey, and I loved that idea so much I made it real.

Because bourbon rightfully plays a wonderful supporting role in this book, I need to know what your favorite bourbon is, and how you like to drink it. And does the book have a signature bourbon drink?

I don’t drink it often, but I do love Maker’s Mark. I also like Four Roses. Bulleit. And I like it neat. I don’t mind a little ice if it’s super-hot out. If the book had a signature drink, that’s what it would be: Maker’s Mark, neat. Preferably on a snowy night by the fireplace.

What’s next for you? What are you working on now?

I’m always working on something! More short story collections, more novels — both YA and adult. I have a country romance novel I’m working on, too.