If your only image of the students of Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School is one of the student activists propelled by the media to the center of the March For Our Lives and Never Again gun violence movements, then you would probably imagine the school to be overwhelmingly white. Save Cuban-American Emma González, the most-recognizable faces since suspect Nikolas Cruz sprayed bullets into the Parkland, Florida school on Feb. 14, killing 17 and injuring many more, all look similar.

Now, students of color at Parkland are seeking to show the full picture. Stoneman Douglas student Carlitos Rodriguez and friends started the online campaign "Stories Untold" – a Twitter account and its own hashtag – that aims to amplify the underrepresented voices and stories of students impacted by gun violence. This includes the students of color at the Parkland school, as well those in the less affluent, less white communities in Florida who are impacted by gun violence at disproportionate rates.

"Our school is very diverse, and the media is not representing us," Rodriguez told HuffPost, adding that nearly 40 percent of Stoneman Douglas’ students are not white. He continued, "We want to represent the minorities that are not in the media: the Latinos, African-Americans, Asians. Our voices are very powerful."

Since its launch on April 2, the "Stories Untold" Twitter account has provided a platform for more Parkland students to disclose for the very first time the horror they witnessed on Feb. 14, including personal accounts from those who were injured that day.

In one video, Stories Untold follows Venezuelan-American student Anthony Borges, 15, and his return to Stoneman Douglas since recovering from five gun shot wounds.

An emotional yet heartwarming return to Marjory Stoneman Douglas since February 14! Anthony Borges is back in the nest and we are all thankful for his bravery ❤️ #MSDStrong #StoriesUntold pic.twitter.com/aEcuoIdPil

— Stories Untold (@StoriesUntoldUS) April 6, 2018

This critique of the one-dimensional mainstream coverage of the Parkland shooting is far from new. Campaigns similar to Stories Untold continue to sprout up, as the same story continues to repeat itself. During an interview with Axios, when survivor David Hogg was asked what the media's biggest mistake was when covering the student activism at Parkland, he replied: "Not giving black students a voice . . . My school is about 25 percent black, but the way we're covered doesn't reflect that."

Emma González, too, has often called for expanding the narrative, expressing the need for the gun control debate to address gun violence in all of its forms and to acknowledge the communities of color who are most impacted. In a moment of solidarity and understanding, she invited students from the West and South sides of Chicago into her gated community in Florida to learn about their lives, work and the many movements against gun violence happening there.

But for some Stoneman Douglas students, this underscored the problem. "It hurts, because they went all the way to Chicago to hear these voices when we’re right here," Mei-Ling Ho-Shing, a 17-year-old black student at Stoneman Douglas, told HuffPost. "We go to school with you every day."

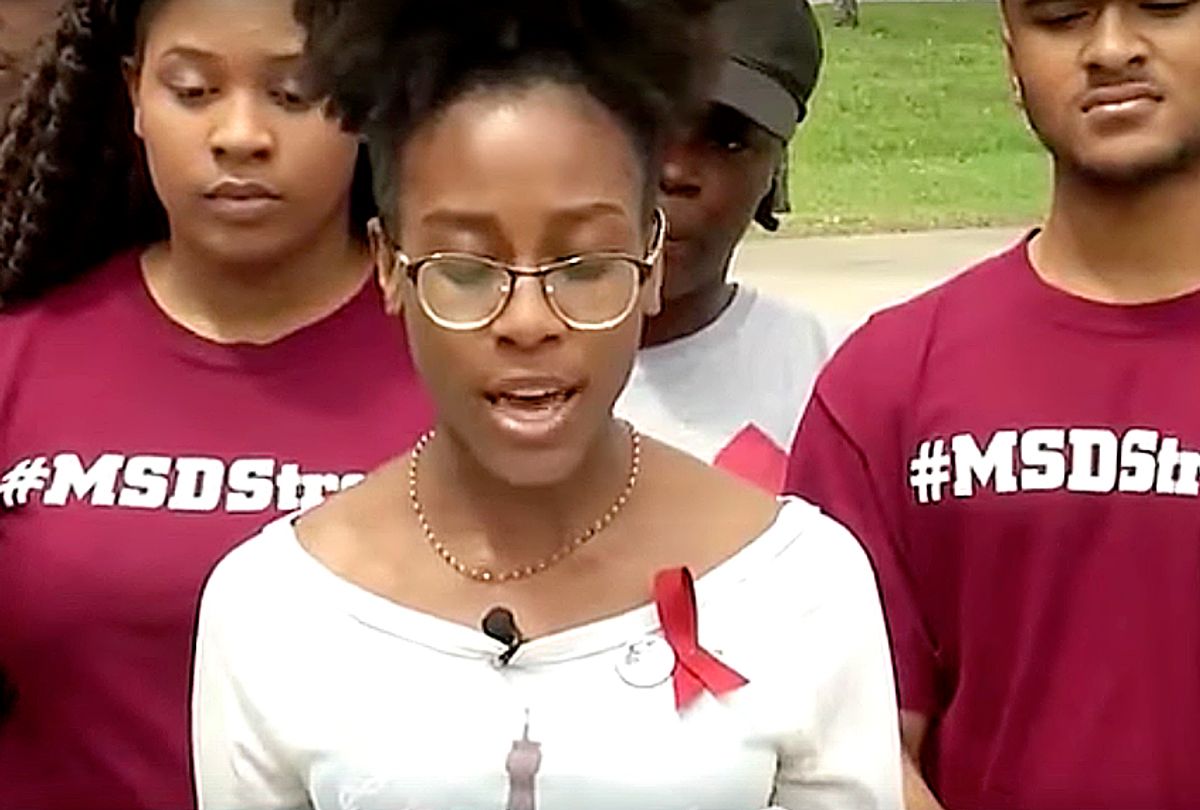

Several black students from Stoneman Douglas held a press conference on March 28 to broadcast their concerns, among them the new danger that they specifically face at school as the result of an increased police presence and whether police violence is being properly included in the March For Our Lives movement. Most importantly, they expressed desire to be recognized and heard.

"We feel like people within the movement have definitely addressed racial disparity, but haven't adequately taken action to counteract that racial disparity," Tyah Roberts, a 17-year-old junior, told Refinery29. "We're not trying to form any rift in the movement. We're not trying to form a separate group. We are proudly representing Never Again," she added. "We're just trying to ensure our voices do not get lost in the movement, as we feel we have before this press conference."

Even if the movement's frontrunners are addressing the racial disparities related to gun violence, the media's coverage of the issue remains problematic. In 2014, The New York Times described Mike Brown — who was unarmed, gunned down on a Ferguson street by a police officer, his lifeless body left in the street for hours — in part as: "Michael Brown, 18, due to be buried on Monday, was no angel." Similarly, when young activists filled the streets to protest the seemingly always unpunished killings of black men, women and children — which are often caught on camera — in Black Lives Matter rallies across the country in Baltimore, Cleveland, Chicago and New York, the FBI's counterterrorism division labeled them as "Black Identity Extremists" and a threat to national security.

In Florida in 2013, young black activists who were part of the Dream Defenders were so outraged by the killing of teenager Trayvon Martin that they occupied the state capitol for 31 days. They protested Martin's killing, as well as the Stand Your Ground law, which made the civilian shooting legal. Gov. Rick Scott refused to call a special session to address the situation. Yet, three weeks after the Parkland shooting, whose victims were mostly white, Scott signed a $400 million school safety and gun reform bill.

A spokesperson from Broward County Public Schoosl later told WLRN that the statement was unapproved and "due to the potential for disruption and breach in protocol, the student was asked to stop and leave the stage."

The mass attention and celebrity donations for March For Our Lives has continued to emphasize how America perceives victimhood and violence. But for this image to finally reflect reality, the Parkland activists must go beyond publicly acknowledging their privilege and criticizing the media's double standards, and as Ho-Shing told HuffPost, "share the mic."

In addition to their black and brown peers at Stoneman Douglas, this includes the activists at the forefront of ongoing movements against gun violence in Baltimore, Chicago and Los Angeles. It is certainly an uphill battle, but it remains an important one if the Never Again activists truly want to embody and practice the inclusivity that they speak for.

"The Black Lives Matter movement has been addressing this topic since the murder of Trayvon Martin, since 2012," Roberts told Refinery29. "Yet we’ve never seen this kind of support for our cause. And we surely do not feel that the lives or voices of minorities are as valued as our white counterparts."

There's much work to do.

Shares