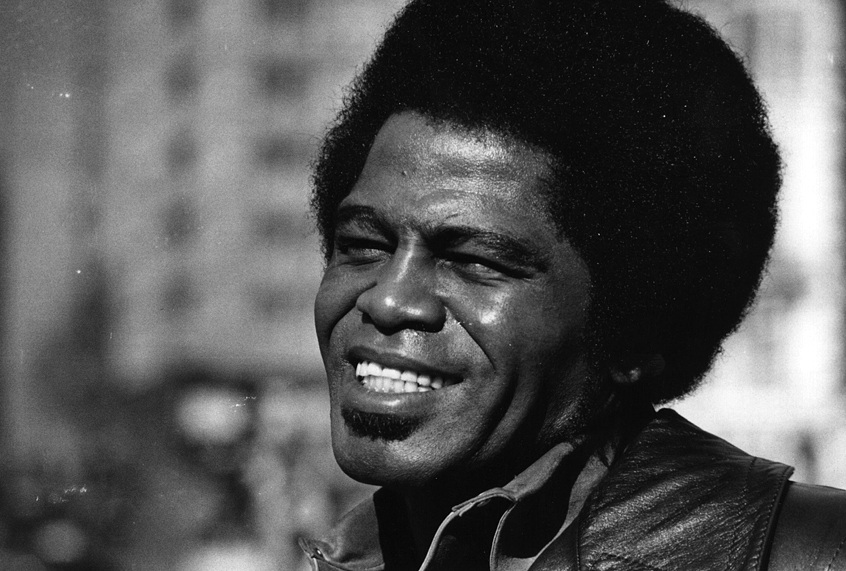

Jabo Starks died last Tuesday at his home in Mobile, Alabama, at age 79. He and Clyde Stubblefield were the twin drummers in the James Brown touring and recording bands during the 1960s and ’70s, when they patented the funk beat in songs like “Get Up I Feel Like a Sex Machine,” “Cold Sweat” and “Say It Loud — I’m Black and I’m Proud.” Reading his lengthy obit in the New York Times the other day, I was reminded of the time I saw Starks and Stubblefield backing James Brown at the Apollo in 1970. It was the soul music equivalent of watching Plato hold forth at the Acropolis, so elemental and powerful was their influence not only on the Godfather of Soul, but on American music itself.

The first time I went to the Apollo Theater in Harlem was deep in the winter of 1968. We had a weekend off from West Point, so two of my classmates and I made the trip down to New York, checked into the Hotel President on West 48th Street, went down to the Village and had dinner at Puglia Restaurant on Hester Street, and then walked over to Spring Street and caught the Lexington Avenue subway up to 125th. When we got out of the subway, an icy wind was blowing. It was around 11 p.m, and we were there for the midnight show at the Apollo, so we walked over and got in the line, shivering outside the theater as snowflakes began to fall.

It was one of those classic Apollo shows, with something like four groups on the bill — I’m pretty sure it was the Four Tops, Gladys Knight and the Pips, Solomon Burke and Joe Tex. A couple ahead of us in line said we were early enough to get the best seats in the house, in the first row of the balcony, which looked right down on the stage only a few dozen feet away. When we reached the box office, we bought our tickets — something like $2.75 for the balcony seats — and followed our new friends upstairs, where sure enough, we got seats in the first row.

Sometime just after midnight, the house lights went down, and the emcee, the DJ Frankie Crocker from WMCA AM radio, stepped out on stage in a sharp looking suit and announced Joe Tex. Before he had finished his first song, someone to my left passed me a bottle of Ripple. “Have some and pass it along,” he whispered, so I did. Before I knew it, the same guy passed me a joint. The show went on for hours, finishing up with Gladys Knight and the Pips doing “Nitty Gritty,” and their classic hit, “I Heard it through the Grapevine.” I remember walking out of the theater into a snowstorm blowing sideways down 125th Street. Somehow, it didn’t seem as icy and bitter out there as it had been when we went in.

We went down to the midnight show a few more times before we graduated in June of 1969, each time making sure to get there early enough to get those seats in the first row of the balcony. But it wasn’t until the winter of 1970 that I made my way back uptown to the Apollo, this time to interview James Brown.

The fashion writer Blair Sabol and I had an assignment from Esquire for a story called “The Politics of Costume.” The idea was kind of sketchy, something about exploring how people had begun to express their personalities in the way they dressed. Blair took the “fashion” end of it, interviewing designers like Betsey Johnson and going out with photographer Bud Lee to shoot people on the street who were wearing head-to-toe tie-dye outfits and fringed jackets and ponchos that made them look like something out of “The Good, The Bad, and the Ugly.” My job was to wrangle a few celebrities to help sell the story. We settled on Little Richard and James Brown, who were almost as famous for what they wore as they were for their music.

Little Richard wasn’t the easiest guy in the world to get ahold of. We finally cornered him in a dressing room upstairs from the Electric Circus on St. Marks Street. When I asked him where he got his outrageous costumes, he said, “My mother makes them for me back home in Macon, Georgia.” He stood up, and reached for a royal-purple velvet cape, and with a flourish, whipped it around his shoulders. “She just sewed this up for me sitting out on her front porch last week. Don’t you love it?”

That was exactly the kind of stuff I was looking for. A week or so later, Bud and I headed uptown to the Apollo to catch up with James Brown, who was doing a week-long run there, two shows a night as I recall. His label, Polydor, had arranged backstage passes for us, so Bud and I headed straight there, thinking we’d be in and out in an hour or so. All we needed was a shot of James showing off one of his costumes and a short interview. Piece of cake.

James had about three layers of factotums and bodyguards, and it took us the whole first night to even get somebody to give us directions to where the dressing rooms were. They were up a set of stairs way in the back, guarded by the third layer of his protective detail. James, the bodyguard said, was too busy to see us. Come back tomorrow night.

Bud and I found a corner of the stage where we could see past the side curtains and watched the show. I had seen The Hardest-Working Man in Show Business once before, at a concert in Washington, D.C., when I was a senior in high school, but I had seats about as far from the stage as you could get and still be inside the venue. Watching James Brown funk up the Apollo Theater from the wings was something else altogether. We could see the sweat fly off his hair as he dropped to his knees during “Please, Please, Please,” and the guy carrying his cape onstage brushed right by us near the end of his set, when James would throw it off about three times, grabbing the mic stand as he went into the chorus of “Try Me” again and again.

We tried again after the end of the second set, but we were told James was already on his way back to his hotel, despite the fact that we’d watched him walk right past us on his way to his dressing room.

The second night went the same way. So did the third night, when we got there way before showtime, thinking we’d catch him as he was getting dressed for the first set. James was too busy. We tried again after the first set. He was still too busy. By that time, Bud and I had made it past the third bodyguard and were waiting upstairs, where we watched him go through the door into his dressing room. When we knocked, someone yelled at us to go away. James was busy. I noticed the door of the room across the hall from James’ dressing room was open, so Bud and I ducked inside, thinking we’d wait and catch him on his way out.

Two women in long dresses sat at tables before sewing machines. It turned out they were the seamstresses from his hometown in Georgia he took on tour, and it was their job to repair the suits he regularly tore each night during his onstage antics, which included doing several full splits. One of the women showed us how he’d torn the armhole to one of his tight-fitting suit jackets, flinging it off during that night’s show. All of his suits were tight, but they were designed with extra fabric in the arms and at the crotch, so they could be re-sewn over and over again.

We hung around the seamstresses’ room for two more nights without budging James Brown from his solitary splendor. The next night was the last night of his run at the Apollo. Either we got the photo and the interview, or with the deadline looming, we had a two-page spread in Esquire we’d have to fill with someone else. Bud and I made our way straight up the seamstresses’ room and set up camp. He wouldn’t see us before the show, even though we were two hours early. Too busy. I caught his eye going into his dressing room after the first set. He waved me off.

By then, Bud and I had become friendly with the seamstresses. One of them asked me what would happen if we didn’t get in to see James. I told her we might lose the assignment. We needed him. It was Esquire! She asked if that meant we wouldn’t get paid. I allowed as how that was a possibility. She shook her head slowly from side to side, tsk-tsking.

She had watched us try and fail to get in to see James Brown about five times by then. She finished sewing a pair of James’ trousers and stood up. She said, “I’ll get you in there. Come with me.” She walked over to the door and lifted the skirt on her colorful floor-length dress, and told me to get on my hands and knees behind her. “Get down there and follow me. You hear me open the door, I’ll give you a kick, and you jump out.”

It was now or never. The hall passageway between the two rooms was only a few feet wide, so I figured it just might work and did exactly what she told me. I got down on my hands and knees and stuck my head right behind her legs, and she reached around and spread her voluminous skirt over my back, and we headed across the hall. There was a guy standing guard outside James’ door, but she went right past him, and I heard the door open. I crawled a few more feet and felt a kick on my shoulder. I lifted her skirt and jumped to my feet and looked around. James Brown was standing there with his shirt off, open-mouthed. Then he laughed until tears ran down his cheeks. “Man, you must want this interview bad, pulling that shit!” he said. I pulled my notebook out of my pocket and asked if it was okay if I brought in my photographer. “Anything you want, man,” he said. He was laughing so hard he almost choked.

I ducked across the hall and got Bud. James got dressed for the second set, and Bud took a couple of shots, and in between, I managed to squeeze a few quotes out of him. He had a guy who made his suits, and James himself designed some of them.

We stayed for the last set of his run at the Apollo. The view from the wings was fantastic, but I missed the Ripple and joints that were passed up and down the first row of the balcony.