I never thought Elvis was the king of anything. I grew up in the era of hip-hop and fact checking, so we knew he got famous off of black music and we were bold enough to scream that in front of the most die-hard Elvis fans.

But Elvis was bigger than his artistic endeavors; he was a representation of the American Dream and the end of an era, with a personal story that goes way deeper than the music and the films he made.

Director Eugene Jarecki dives into the life of Elvis in his new documentary “The King,” a film about the rise and fall of Elvis. With music by Immortal Technique and interviews from artists who grew up in the Elvis era from all over country, Jarecki delivers a raw understanding of who the late pop icon really was.

Jarecki and Immortal Technique sat down in Salon’s studio with me recently to talk about Elvis and what he meant.

Our conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

I admit that my journey into learning more about Elvis kind of ended after I heard of him initially as a young teenager. You guys gave me a lot of information that I feel like a lot of people need to know.

I learned about Elvis through Chuck D; that was my introduction into Elvis. How did you hear about Elvis? How did he get into your lives?

Eugene Jarecki: Growing up, I mean, I was marinated in Elvis because of [being] a young white kid in America. Elvis is one of those 1950s icons. I was born in the late ’60s, and early ’70s, growing up, that was from another time, but it was cool. It was like candy-colored chrome cars.

Maybe one of the first icons.

Jarecki: Yeah. I didn’t learn anything critical about that until Chuck D. Chuck D is also the person who puts a more complicated story on my radar than I had before.

Watch the full Salon Talks interview

Eugene Jarecki and Immortal Technique discuss “The King”

Who was also in the film as well?

Jarecki: Yes, he is.

What about you, coming out of Harlem?

Immortal Technique: I mean, I grew up in Harlem, so I understood that the rock music that was made, rock and roll at that time, was something that was borrowed from a totally different radical beat, and I use “borrowed” in the lightest [way] as possible.

Jarecki: Very kind of you.

Immortal Technique: But, at the same time, I think that for people that think this movie is just ripping Elvis apart, no, it’s a cautionary tale about people wasting money, right? It’s a cautionary tale — not just about Elvis but America, and that’s what I learned about him.

I had a more complete picture of him.

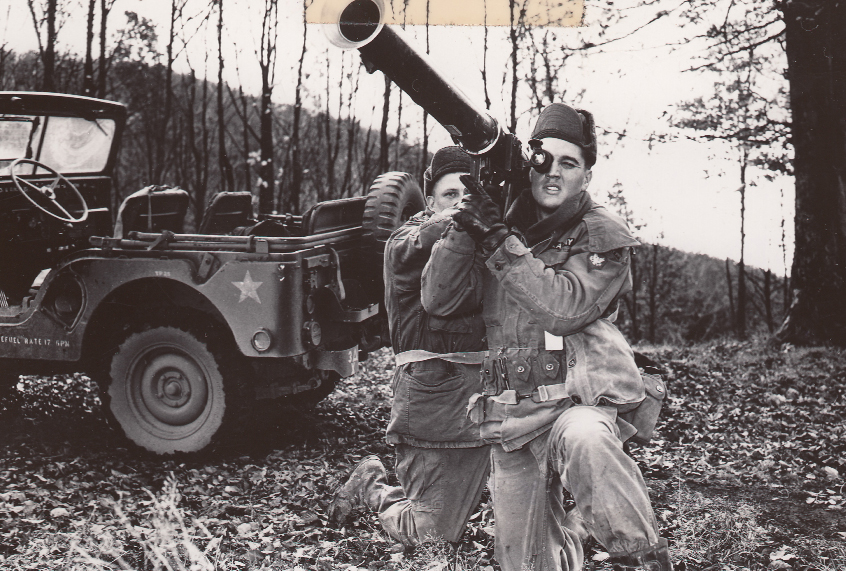

He was in the service [and] he got hurt somehow. He needed drugs, and it’s the same way you see in Harlem people that can’t afford those pills, right? What happens when you can’t afford the painkiller pills when you got a ripped ligament or you got pieces of shrapnel in you? All these veterans out here, what do you when you can’t afford the pills no more, and the government can’t subsidize them? Go get yourself a $10 bag in Harlem.

It’s crazy how, if you had somebody who was as celebrated as Elvis, [the attitude is] “Oh, he just had a problem.” But if you’re a regular everyday person and you’re a drug addict —

Immortal Technique: That’s the point. I think, God bless you for bringing that up because it is an old saying that rich people are alcoholics, and poor people are drunks.

No, everybody’s vulnerable. Right? Even somebody who was on top of his game, who was an icon.

My mother knew about Elvis when she lived down in Peru; he was a cultural icon that expanded way out of America. His music played on radio stations all over South America, all over Europe, all over Asia.

But, he never did shows out of the country.

Immortal Technique: Right.

That’s something I learned from the film.

Immortal Technique: The crazy part is that people didn’t even know that he was on this stuff at that time. It became very clear afterwards, right, and then during the later part of his life. But in the very beginning when his drug use started, and you see in the film, pretty much during his military service, but no one knew at that point. When he was making 12 movies a month down in Hollywood, nobody knew that he was on this stuff. Nobody knew you’re vulnerable.

Jarecki: It’s like the price of power. Elvis — like America — he’s born beautiful, young. He rises out of nowhere, just like America did where we kind of took the world by storm. One day, there was no America, the next day—

Immortal Technique: We took America by storm. You take a lot of people by storm.

Jarecki: We all have this creation myth where America is young and beautiful, and it’s like we forget that genocided the Native American. We built the thing on the black slavery, but there is this mythology, and even in the modern era, we know that Martin Luther King said that the arc of history advances toward justice. What does that mean? It means that here, America, the American dream that was supposed to be never was, but — was supposed to be this idea that you can come out of nowhere, rise to the top. Elvis starts in the sticks of Mississippi, but he ends up The King. That’s all well and good.

But, that American dream, the more I look at it and thought about Elvis in the context of it, it was an American dream for white people. It was really an American dream for white men. It wasn’t there for black people. It hasn’t been there for black people. It wasn’t there for women. It wasn’t there for minority people. The reality is that Elvis started out for me as this kind of ideal of our childhood, but it didn’t take me long to start to understand that whatever his intentions were, he’s just a human being. The use of Elvis has been to make an icon that is Kool-Aid for Americans to drink to misunderstand their history.

It’s interesting you say that because the one thing I saw in the film that I wasn’t really looking for was frustrated white men. It’s a frustrated white man with the country and what it used to be, versus what it is now. You think that dream kind of died with Elvis in that era?

Jarecki: Yeah. I mean, Elvis’s generation is the generation of white men who thought the world was going to go their way. It is now starting to not go their way, which is why you see it’s so angry. That group of people, the he-who-shall-remain-nameless, this person we have in the White House — I don’t plug failing brands, so I’m not going to use the name. But I will say that that force that’s in the White House, what he’s unleashed is the anger of the big white man and losing the control he felt [he] had, and he did have. Big white men have run this country into the ground and run the world into the ground for a very long time. As they started to lose their grip, a leader figure comes into view who says, “I’m going to work your anger. I know you feel it. I’m going to turn it into a force to promote me, my brand. I’ll sucker you into this because you are vulnerable through that anger pathway, and I’ll exploit you.” That’s what’s happening right now. My heart goes out to them even through they’re angry.

It’s kind of connected. Those people who support that big failing brand, we’ll call it the—

Jarecki: The brand.

Forty-five.

Jarecki: Forty-five.

Those people that support 45, they’re kind of the people who grew up daydreaming and fantasizing about Elvis in that dream.

Immortal Technique: But, I would say that’s [true] partially, but I think also, they were fed a group of stories about how the economy would work, right? Even if you bring up the most vociferous thing and the most dividing plot line that you could possibly have, especially even now in America, right? You take up something like immigration. It’s a very simple thing to explain to people. There’s a banker, a worker and an immigrant at the table. There are 20 cookies on the table. The banker steals 19 cookies, and then he tells the worker, “Look out! The immigrant’s going to steal your cookie.” From the very beginning —

Jarecki: You only have one left.

Immortal Technique: From the very beginning, it’s not just poor working class white people. They were the ones that were duped into following this economic model by really, really rich people. Then, you have the powers of right-wing talk radio and right-wing TV that say, “Oh, socialism is the enemy.”

All right, fine. You want to have a conversation about left versus right-wing politics? Who gave you the ability for your wife not to get fired when she got pregnant? Who gave you an eight-hour work day? Who gave you the ability to have 40 hours [in a standard work week]? Who gave you no child slave labor? That didn’t come from Bayer, right? That didn’t come from JP Morgan. That came from organizing and socialism.

Then, we get into the prison to school pipeline and we examine Elvis’s life; you can see that his father was in prison, right? He was adopted by the black church.

From the very beginning, the interesting part about the story that Eugene brings up is here is a guy who started out very similar to America in the sense that he had a lot of people to rely on to help him build a country. Now, whether he acknowledged them or not, that’s what we talk about, right? Where America said, “OK, thank you for the land, indigenous people. Thank you for the idea that a federal government can rule over state government.” That’s an Iroquois Confederacy. We all know that’s where the American Congress borrowed a lot of their ideas from the Founding Fathers. Then you have free labor from poor working class people and from slaves.

Then you combine these two things to put us economically ahead of Europe, which was the whole plan, but the problem is then you slam the door on the people behind you when they act like they didn’t help. That was the main issue that I had in discovering Elvis. He didn’t wear a hood, right? But at the same time, he closed the door behind him. He was the person who was in Muhammad Ali’s era. He was in the civil rights era. He was in the era of Rosa Parks, MLK, Malcolm X. When he had a chance to speak through to power on camera — you can see it in the movie. He says, “Well, as an artist, I don’t feel it’s my place . . . ”

That reminded me of Michael Jordan saying Republicans wear Jordans too, so I can’t really speak on those issues.

Jarecki: Jordan back then, he said, “I’m not your role model.”

Immortal Technique: The bottom line is I think that when you look at these particular cases where you have an overarching amount of injustice, I think the trick to creating injustice is also to fool the people that are committing injustice to think that they are the ones that had been treated unjustly the most. That’s why you have this fear of working class white people to say, “Oh, my God, everything for me is being snatched away — Elvis, my job.”

Okay, let’s have these conversations. Elvis isn’t being snatched away from you, we’re putting him into context for your children that are stuck on opioids and heroin. Get that f**king needle out your arm.

Get these stupid pills out of your mouth, not because oh, my God, we don’t want you to have fun, but we need you in this fight.

It’s that nostalgia that they want to hold onto, but people don’t want the truth.

Immortal Technique: But the other part of it is that when you look at it, you can say, OK, did you, as a working class white person, lose your job to an “immigrant”? No, you lost your job because a greedy capitalist said, “Hey, I can exploit this person and pay them way less than you. I don’t have to give them any benefits, and then I got used to exploiting this person. So now, you, as an American worker, I [can’t] even afford to pay you what I would because it would mess up my private mortgage.” That’s who took your f**king job!

It’s so clear. What is it that people don’t get about that? I think the Secretary of Labor was a guy who was like, we should use machines because they work all night, and they don’t want to take vacations. These are the people that you put in office.

Jarecki: This all started a little bit in the modern era. This started with Ronald Reagan, because the New Deal Society had, in fact, brought America together to a degree . . . this country has always had failures. It’s always had fractures. We’re always talking in relative degrees of progress. There was some progress made by the new deal toward a greater more just society, then there was some progress made in the civil rights era toward that. There was this process where we seem to be heading somewhere, however flawed. Reagan seized upon that, and all of those who supported Reagan seized upon that to say, “Let us stop the steady march toward a real and more healthy democracy in this country.” They unleashed the dogs of capitalism to hijack this society. We now live in a society where everyday people understand that this place is run by the .00001 percent for their benefit, at the detriment of everybody else. That’s a fact of life.

We know that our vote barely counts. We don’t even know that we can elect somebody if we want them. It is controlled and manipulated. All of that speaks frankly to how we got here, and Elvis is a part of that, not because he tried to do anything bad. Elvis is an artist. He’s a musician. He’s somebody who loved black music and it radiated through him. He sent it out to the masses. That was what he did, and then he was the first of his kind. He was the first young country boy ever to have supernova power thrust upon. This is not about attacking Elvis, it’s actually about using Elvis as an example of how something you love can be destroyed.

The American people are Elvis. They have been hoodwinked. They’ve been hijacked by a system much larger than themselves, and it will come to them to make a choice or not. I think we’re seeing a bit of that these days to make the society what they wanted to be or let it be continually dominated by those above them.

Both of you guys referenced Elvis as growing up in a black church and utilizing that music to be able to gain all of his success. But Brando marched with King, and other people at that time marched with King, but Elvis chose not to. Do you think he had love for the people he got his music from?

Jarecki: My take on that comes from Chuck D, obviously, to whom I turned. But when I first went to interview Chuck D for the film, I thought Chuck D was going to sit down and basically say, “Elvis was racist, period, final.” What he said is, “Let me be very specific where I accuse him of racism.” When he is playing black music as a white kid in the ’50s, that is a courageous thing to do. That is culture. He said, “You wouldn’t tell a young black kid not to play Mozart because he doesn’t have a German root. That’s culture. He should do that.” Elvis magically should have been playing black music if it was a genuine thing to do for him, and it was. That’s not the problem. The problem is then that the white music business makes him The King and leaves Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley, BB King by the roadside and doesn’t give them the credit they deserve, does not give them the money and the equality they deserve.

Elvis participates in that, but he’s still pretty much an innocent here. He’s still just doing the music and being an artist. It’s later, as you point out, that we know what the black community did for Elvis. But when the black community needed every bit of help they could get in the civil rights era, where was he? Why didn’t he take that love that I think he genuinely felt that radiated through him from the songs he listened to and the church experiences he had and the friends he had? Elvis had black friends at a time where white people wouldn’t be caught dead with a black person.

Was he responsible for that?

Jarecki: Yeah, I bet.

Immortal Technique: One thing that’s important to bring up is that he could have put the least amount of minimal effort and to just say “Hey! Everybody deserves to be treated like a human being.”

Jarecki: By the way, privately, there’s a million stories, [but] we’re talking about where it counts. We’re talking about why I mentioned Charles Barkley earlier. I watched the documentary the other day, a wonderful documentary about Professor Edwards in California, the people should look up. He’s the guy who whispered in the ear of the athletes who did the Black Power Salute all the way back then at the Olympics. I didn’t know it, but he’s also Colin Kaepernick’s adviser. I didn’t know that one man is a brilliant adviser of radical activity in this country. One of the things that happened in the context of that is, he talked about what significance there is in artists and athletes and other famous people taking the positions they took.

That was a dark year in this country where people like Michael Jordan and Charles Barkley specifically said, “I’m not here to contribute to society. I’m here to get mine.” Well, if you’re willing to do that, then don’t be surprised when the society becomes a slippery slope away from dignity for everyday people, away from democracy, because you’re saying that, “Capitalists rule, I’m just one of them.” We bid on that slippery slope for too long, but I think we’re getting away from it. I think some good things have happened, weirdly enough, under this brand 45. The hatred that people have for 45 has actually become a tool for creating real reform in this country. We’ve seen it in a million new directions.

You need an idiot to breed revolutionaries? You need an idiot to lead and breed revolutionaries? It’s crazy because people don’t really take their stance. I feel like that’s the reason why we have a lot of negative things going on right now. What do you make of the crisis at the border?

Immortal Technique: I mean, like I was saying to people before, I feel like it’s not necessarily just an immigration problem or just “Mexican/Central American problem.” It’s always been a Native American problem. They used to steal Native Americans’ children, people’s children [and] put them in re-education boarding schools. I’ve visited one of these boarding schools, or the remnants of one, with an activist who’s now gone — rest in peace to Russell Means. The brother took me to one of these schools and with another activist named Pete Swift Bird. I really appreciate them taking time out of their day. They led me to these classrooms where children had engraved tears in their faces and eyes and other people’s hands on them. [The] drawings that I saw of the things that had happened to these children were horrible. It’s hard to believe that that’s not happening now, but it brings it back to the reality.

This country [has] always had a Native American problem, and now it has a problem with Native Americans that speak Spanish. I know in other people’s mind, they want to chop us up into little categories, “Oh, no. You’re just Mexican. You’re not . . .” Where do Mexican people come from? They come from indigenous people, up here in the north for people who don’t understand. We’re Anglicanized natives, which is why I’m speaking to you without an accent perfectly, all that stuff, right?

But if we go down south, then we run into people who are Latinized indigenous people. This is not hard to understand if you do a tiny bit of history, and I don’t mean this to be facetious. I mean, arm yourself with history because more often than not, people would say, “Okay, this happened under Reagan.” Great to point out. This happened under Clinton, then people would say, “This happened under Obama.” Great! We can condemn all those things, but I keep asking the question, do you support the children in cages? Yes or no? This happened under Obama. You’re right, that should be condemned. Do you support children in cages?

I’m going to keep pushing on that one. That’s the one I’m going to keep pushing again and again and again until I break you, because we’re going to get to a point where the niceness stops and I’m afraid, brother, that happens whether you’re talking to conservatives or liberals in this country.

At some point, when I disagree with you or I try to teach you something new, people are upset or offended. Now, we love to say on the right side, the right level, to say, “Oh, the facts, the facts are all we care about.” Fine! Then, factor in the historical fact, because right now, all we have is a rudimentary amount of history being taught by a human teleprompter on Fox.

The right cares about facts. That’s a new one to me.

Jarecki: It’s interesting to put Immortal and me next to each other, always, because he comes from a perspective on the world that comes out of an indigenous history and a knowledge of so much of the coming together of cultures here. I come from Jewish people who fled Nazi Germany, who fled Russia. He calls them cages; I call them juvenile concentration camps. Now, people say, “What do you mean juvenile concen — they’re not killing anybody.” We didn’t kill in the concentration camps. Jews were killed in the death camps. The concentration camps were simply the act of putting cages together, as he says, and concentrating a certain type of people in them.

Immortal Technique: And dehumanizing those people.

Jarecki: Right? What you have to notice about the society, and this what we should be thanking Mr. 45 for, is that he has shown us the true face of the system. America is extremely good at presenting a narrative about ourselves. We’re a romantic narrative, home of the free, land of the brave. We cut out the third stanza of the national anthem, which actually is very racist. We pushed away —

“No hireling or slaves should be free from the gloom of the grave.”

Jarecki: Indeed. Why don’t we sing that more often? We keep these dark parts of our history out. These are very, very challenging parts. We tell ourselves a bunch of Kool-Aid narrative. What this guy has done is poisoned the Kool-Aid. He’s basically come forward and said, “Who we really are is a country that will have for-profit institutions incarcerating children.” That’s a motivator of public policy. If you don’t like that, get engaged. That’s the beauty of this, because it’s a time to get engaged because we now have no longer the ability to delude ourselves.

This question is for both of you. What is this film going to do to Elvis’s legacy?

Immortal Technique: I think that honestly, it’ll expand it. Maybe not in a way that people who love him and cherish him as an icon will expand it, but it would expand it in a way, for example, if Elvis is Jesus to them, this would expand in the way you would if you found books written about Jesus that weren’t in the Bible.

I think, if anything, it adds dimensions rather [than] takes away from the legacy. It adds a dimension of drug addiction as a dimension of understanding the financial relationship behind with the Colonel. That’s another parkour for having a comparative analysis between that and America. You [got into] a really bad deal, right? You went from a new deal to a terrible deal, my dude. Who gets all the money from this 50/50 split? What am I giving up? My creative control is gone.

Everything that I wanted to do with the country is gone, so freedom and democracy are not synonymous with capitalism. That’s what this movie, I think, brings out in a musical sense but then leaves it for the audience to decide and say, “Okay, what am I really going to take if I’m a drug addict, right, and I’m struggling with drugs. I can look at Elvis’s life and say, “Here’s a guy who was way above where I am, the first cultural epic of his time, and he ruined himself with this.” Another one can say, “Oh, man. He overworked himself, overproduction, you know what I mean? Not being involved in other things.”

I think it’s a cautionary tale for everybody.

This is the dude that kind of shows and mirrors the story of America. A guy who made it because of the help he had. No one ever makes him alone to close his back on the people behind. America built something that was totally new. We don’t want a religious state, right? We want something that’s open to everyone. All men are created equal, but then close the door behind everything and then forgot about what he was doing.