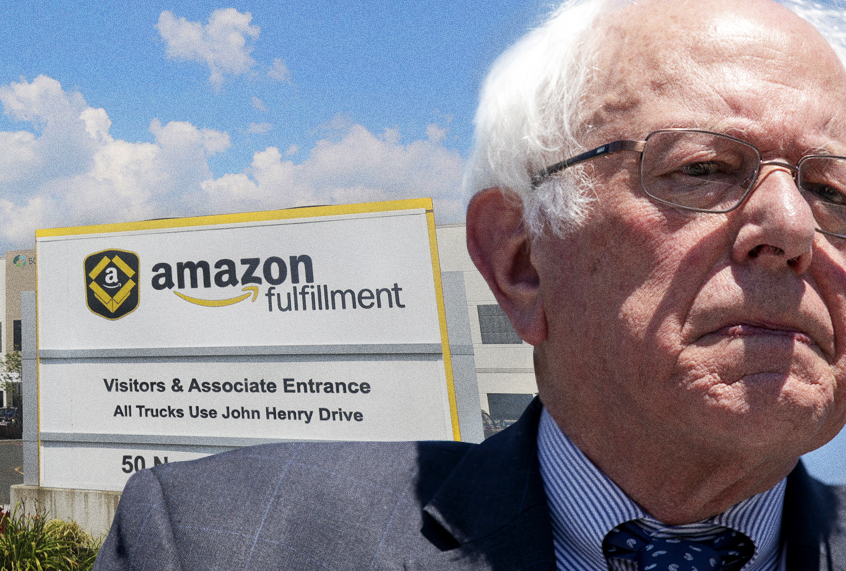

For Senator Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., Amazon Prime Day called for a different kind of PR campaign: one that drew attention to the glaring inequality between Amazon’s CEO Jeff Bezos and his employees.

Indeed, while workers at Whole Foods (one of Amazon’s acquisitions) around the U.S. have been pushing Amazon Prime memberships onto customers to commemorate its sales event known as “Prime Day,” Sanders has shifted the focus from the tech conglomerate’s sales day to its underpaid, often mistreated warehouse workers.

Jeff Bezo’s newly renovated home in Washington DC will have 25 bathrooms. Meanwhile, Amazon workers skip bathroom breaks in order to meet their grueling work targets. #CEOsvsWorkers

— Bernie Sanders (@SenSanders) July 16, 2018

It is a timely campaign considering Bezos’ wealth has been making headlines. According to a Bloomberg report, the magnate has a net worth of $150 billion, which now makes him the richest person in “modern history.” That is reportedly $55 billion more than Microsoft Corp. co-founder Bill Gates. Meanwhile, many of Amazon’s warehouse workers — those who ship, sell, and assist in the timely deliveries of products — are struggling to make ends meet.

On Tuesday evening, Sen. Sanders hosted a town hall titled “CEOs vs. Workers” — which streamed on Facebook Live — where workers from Disney, Walmart, McDonald’s, and Amazon spoke about their unfair work conditions. Sanders invited all of those companies’ CEOs, including Bezos, but none of them showed.

“A significant percentage of workers who work at Amazon [are] working for wages so low they are also dependent upon government programs,” Sanders said at the town hall. “But that is only half the story because a lot of people who work for Amazon don’t actually work for Amazon because they are independent contractors”

Seth King occupied the Amazon worker seat at the town hall, and recalled the time that he worked at a warehouse in Chesterfield, Virginia. King, who is also a veteran of the U.S. Navy, said at first he was optimistic about working at the warehouse. He was excited he was going to get benefits and a 401k, but that pretty quickly he realized those benefits were hard to use because the company burned out their employees at a rapid pace.

“Their model is basically [a] revolving door of bodies,” he said, a practice that is known in business and labor circles as “churn and burn.”

King said he was not allowed to sit down or talk to other people in the same aisles. If you were caught conversing, according to King, an employee would get written up. He described the environment as “depressing” and “isolating.”

“I was so depressed and I kept telling myself if this is the best life is going to get why am I even still here?” he said at the town hall.

King also said that the goals were often unattainable, no matter how hard he worked. He eventually left his job after only two months.

Conditions at Amazon’s warehouses have long been under scrutiny. In 2011, The Morning Call, the newspaper of record for Allentown, Pennsylvania, published an exposé on what it was like to work at the local Amazon warehouse. According to the report, the Allentown factory reached a heat index of 102 degrees, and claimed that 15 workers collapsed because of the heat that year. Following the exposé, Amazon installed air-conditioning in the warehouse, according to reports.

In 2015, three plaintiffs filed a lawsuit against Amazon alleging wage and hour violations in the company’s San Bernardino, California, warehouse. According to the report, workers were allegedly required to participate in individual security searches each day that cost 20 to 30 minutes of unpaid work. In 2017, workers at the Sacramento, Calif., fulfillment center also filed a class-action lawsuit. They alleged that they had also been denied rest breaks and overtime pay.

Despite facing multiple lawsuits that have spurred some company changes, some workers claim conditions are still unfair.

In January, Salon spoke with Brenda Hardin, who works at an Amazon fulfillment center in Kenosha, Wisconsin. Hardin told Salon she makes $12.75 an hour, but does not receive benefits — save for $9.62 that Amazon pays toward her health insurance each week.

“This is the most prestigious company in the world, and for part-time workers, it’s like a modern-slave shop,” she told Salon.

Aside from Sanders’ campaign against Amazon, it appears to have been a rocky Amazon Prime Day thus far. Following the beginning of its 36-hour annual shopping holiday, the website reportedly experienced a glitch.

Amazon responded to reports about the glitches on Twitter.

“Some customers are having difficulty shopping, and we’re working to resolve the issue quickly,” the company posted. “Many are shopping successfully — in the first hour of Prime Day in the U.S., customers have ordered more items compared to the first hour last year.”

— Amazon (@amazon) July 16, 2018

Across the pond, in Germany, some workers have celebrated Amazon Prime Day by going on strike.

“The message is clear — while the online giant gets rich, it is saving money on the health of its workers,” said Stefanie Nutzenberger, an official responsible for the retail sector at the Verdi services union told Reuters.

Amazon workers in Spain are on a three-day strike, according to Reuters, and in Poland, some have staged a work-to-rule, a type of labor action that is essentially a slowdown.

Some advocacy groups back in the U.S. have taken a stance against Amazon for Prime Day in their own ways, too. Color Of Change, the nation’s largest online racial justice organization, issued a statement in response to the Amazon Music Unboxing Prime Day Concert in New York City.

“We are at a crucial time in our country where white supremacy and hate groups are on the rise. By failing to remove hate merchandise, including Confederate, anti-Black, Nazi and fascist imagery from their platforms, Amazon is facilitating the spread of racial violence and hate across this country,” Brandi Collins-Dexter, Senior Campaign Director at Color Of Change said in the statement. “Color Of Change has long been targeting corporate enablers of white nationalists and neo-Nazis. Last year, we launched our #NoBloodMoney campaign to track which companies profit from donations given to white supremacist groups in the aftermath of Charlottesville. Through that campaign we successfully worked with PayPal, one of the leading payment service providers, to stop processing payments on white nationalist websites.”

“We encourage Amazon to re-evaluate what material is being sold on their platforms,” Collins-Dexter added. “Amazon has a duty to communities of color to take a stand against white supremacists and refuse to be their vehicle for hate.”

Meanwhile, Bezos has remained pretty quiet on Twitter per usual. Perhaps he is busy eating an iguana again.