Both as a symbol and as an organ, humans modern and ancient have, perhaps moreso than any other body part, been fascinated by the human heart. Today, doctors have managed to do what the ancients likely thought impossible: build an artificial heart. While artificial hearts are yet to be a long-term solution to keep someone alive who is dying from heart disease or other heart-related illnesses, they have existed for years, and some patients have great success stories regarding using artificial hearts. Given the pace of mechanical and bio-technology, it is worth asking: Why hasn’t a viable artificial heart, one that can work long-term, been invented by now? And what are the hurdles to creating one?

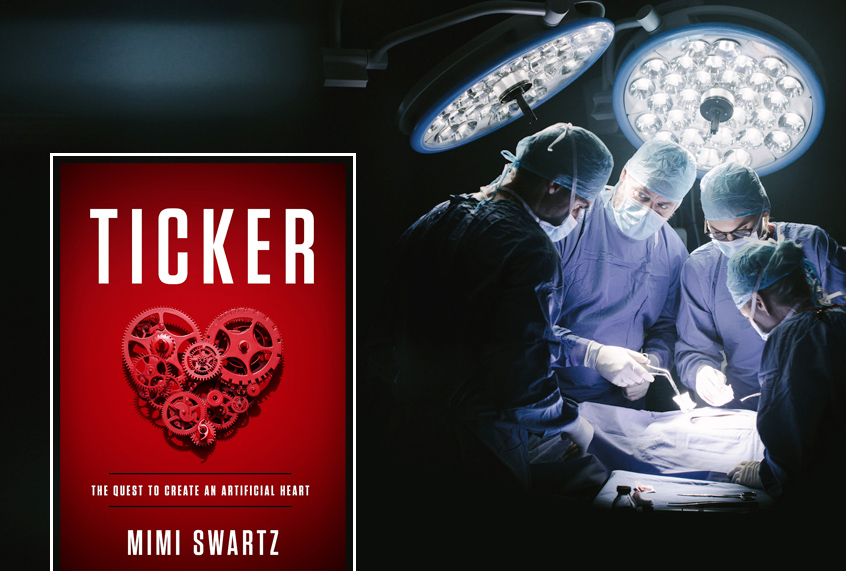

It is precisely this, the astonishing quest to build an artificial heart, that Mimi Swartz documents in her riveting new book, “Ticker: The Quest to Create an Artificial Heart,” which arrives on bookshelves on Aug. 7. In it, Swartz writes about the pioneers and famed heart surgeons Bud Frazier, Michael Debakey and Denton Cooley, and also about patients fighting for their lives. From her detailed scenes in the operating room, to piecing apart doctor feuds, this compelling narrative raises questions about the ethics of regulating lifespan beyond nature’s expiration date.

Salon sat down with Swartz, who is a longtime executive editor at Texas Monthly, to discuss her book and the human heart. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Nicole Karlis: In “Ticker,” you start in the 1950s, but you cover a lot of time in the present day. Can you explain how you landed on this idea, and why you felt it was a story that needed to be told now?

Mimi Swartz: Well, it’s sort of funny because I was working on a magazine story for Texas Monthly at that time and I was interviewing this wonderful artist named Dario Robleto. He had just moved to Houston and he started talking to me about all these heart surgeons — he was new to Houston — so this was all new to him. He was talking about Cooley and DeBakey and how fascinated he was with them and their feud. I’d been looking for a new book for years [and] it’s like he gave me a set of fresh eyes and ears and I suddenly thought, “Oh my God. If you combine that with what Bud Frazier is doing now, this is a 50-year span.”

I didn’t think Cooley and DeBakey alone were a book. I didn’t think Frazier alone was a book, but once I realized that timespan, then I thought, “Oh my God, this is an incredible book.” That’s what happened.

This is a story about the quest to build an artificial heart, but it is also just as much a story about Bud Frazier, though, in my opinion. He’s an important part of the quest, but there are other important figures such as Domingo Liotta, who is the first creator of the artificial heart to be used in a human. Can you share more about the decision to make Frazier the most consistent protagonist of the story?

He was there at the beginning. He was my through-line. I’m friends with Lawrence Wright, you know, the incredible Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter, whom I just know as Larry. He always talks about donkeys in his books. You find characters who can carry your story or certain aspects of your story. I realized that because Bud had been involved in the quest to create an artificial heart for 50 years, he was the most willing donkey.

He also became the main character, though, because he’s a great story-teller. He’s really entertaining. He’s really smart. I think because he reads so much. He just brings more to the table than your average heart surgeon.

Yeah, and it’s interesting you say that, because in the book you do often allude to what the average heart surgeon is like.

Yeah.

All of your protagonists in this narrative are men, though. I’m wondering if you’ve ever thought about how it might be different if women were at the forefront of this quest?

Well, yeah. It kept occurring to me that there weren’t any women. I think now that’s changing. There are a lot of women cardiologists, but there still aren’t that many women heart surgeons because it’s such a boys’ club. I think women’s symptoms are different [than men’s] and I think it’s helped enormously to have female cardiologists who can tell you, “This is what you’re looking for. Don’t ignore this.” In the past, I think so many women were misdiagnosed. There were so many women whose symptoms were ignored or they were told, “This is stress-related” and so they died of heart disease. I think that’s changing, but it’s taking a long time.

Your descriptions from inside the operating room, especially during that one scene, during a heart transplant, they’re incredibly vivid and captivating. But they are objective. Can you share more from a personal point of view what it is like being a journalist reporting from inside the operating room during a surgery like that?

It’s very humbling. I’ve seen other surgeries. I’ve seen breast implant surgery, and you kind of just have this vague nausea that you have to control, but when somebody opens the chest and you see the heart beating — I hate to use this word, but I mean it’s truly awesome. Not in the way that we use that word now, which kind of cheapens it, but when you see them cut out the heart and then put a new one in, and see it start to work again. On the one hand it’s mind-blowing and then on the other hand you think, “Wow, it really is like plumbing,” because they take out one bad part and put in a new one.

It’s like seeing another planet. You can’t quite get your mind around that.

I’m wondering if your perspective on the human heart has changed. Is it just a pump, a muscle, or is it something more?

It’s more to me. This goes back with my friend Dario, the artist. I think Dario definitely believes that there are these brain-heart connections. I do too. I can’t really believe that it’s just a pump.

I think it helps if you’re a surgeon to think it’s just a pump. You’re going to go in there and fix this plumbing and get out again. I think you know in your life if you see somebody you love, or you’re frightened, or there’s something spiritually transformative — you feel it physically in your chest. I think somehow that speaks to me that there’s something a little more there.

I know Dr. Frazier will hate that I say that, because that kind of belief, it’s hampered the research. The more spirituality you ascribe to it, the less people are likely to agree to donate their heart to medicine and stuff like that.

Has your perspective on being alive changed at all since writing this book?

My father was dying the whole time I was writing this book and I kept thinking, “You know, would I put it in my dad?” My answer was no. I think that what struck me most, and this may sound obvious, is how desperately people want to stay alive. I mean, I think, again looking at my father, he was ready to go at 90. Most people are not ready to go at 40, 60. They’re just not. They have so much more to live for and will do anything [to live].

How would you describe the current state of the quest to build an artificial heart?

Well, I think that they’re getting closer and closer. Bud keeps saying, “Well, we’re 18 months away,” and they’ve got to jump through a lot more hoops. One of the other things that interested me is that they couldn’t make this heart until there’d been other technological changes. You know, you can have the idea to make something, but if the technology doesn’t exist, you’re not going to get there.

Do you think that this quest intersects with the quest to live forever? Or do you think they’re different?

I think… that’s a really good question. Again, I’m not sure how many people are really going to want to live to be 102 just because their hearts keep pumping when they’ve got arthritis and they’re half-blind. I see the device as something more to help people who are younger and in middle age who are sick. I think we all think we want to live forever, but again, watching a generation of older people, there does seem to be a time when most people are ready to go. Right? Cooley was really interesting in that regard, because he was really ready to go. He’d had enough. He’d had a great life and it was time.