“Masses move as well as asses do.”

Boots Riley has been the chronicler of American poverty, inequality and racism for the past three decades. But his chronicles do not evoke sadness for the poor, nor do they evoke disdain. There is humanity amongst his characters, people who have not surrendered to their situation but who find ways to survive, to laugh and to struggle.

In “Steal This Album,” the second release by The Coup — made up of Boots and the late Pam the Funkstress—there is a beautiful ballad called “Me & Jesus the Pimp in a ’79 Granada Last Night.” It tells the tale of Hey-Zeus, whose “pimp name is Jesus,” and the ride they take in a Granada — the Ford Motor Company’s attempt to compete with compact and fuel-efficient East Asian and German cars. The car did not succeed. The failure of American manufacturing and the flight of American capital set the terms for the broken history of American cities. This is a failed car in a struggling city, with Jesus — a pimp — in the passenger seat getting ready to be shot at the end of the song. But before we get there, Boots says, “There’s beauty in the cracks of the cement.”

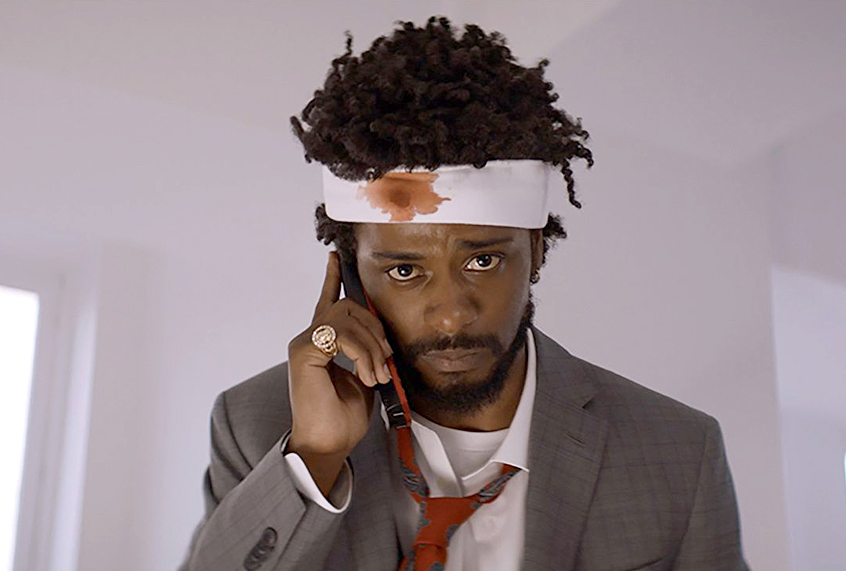

The world of the working class, the poor and the oppressed is not a world to be pitied. There’s beauty there too. In “Sorry to Bother You,” the debut film from Boots, there is one scene that captures the essence of this idea. Our main characters are in the car of Cassius (Cash) Green, a car that barely moves and that is refueled with pennies rather than dollars. It is raining. The windshield wipers are tied to rope, which must be pulled from the inside of the car. The characters laugh as they slosh the water across the windshield. The audience laughs with them. It’s time to dance. It’s time for revolution. No gap between them. The Coup’s first track — “Dig It” — gives the order, “Masses move as well as asses do.” No need to be depressed. Get a move on.

“Trump Trump check out the cash in my trunk.”

You can’t understand Boots Riley’s film if you don’t understand that he hates capitalism. His hate is pure. There is elementary Marxism here. The few that dominate property hire the many that live hand to mouth and then squeeze these workers to work harder and more efficiently. Rewards are offered, but these are illusionary. Only a handful can advance to the next level, but to do so they must break all ties with his friends. They must fabricate a “white voice,” denigrate their own cultural worlds, and uphold standards and sounds that are alien to them. Advancement has its price. The well-named Cash Green’s odyssey through the wretched world of telemarketing to the higher reaches is instructive. He begins selling encyclopedias and rises to sell humans and weaponry. To gain power, one must sell power. The profits from such sales — of people and guns — is far greater than the profits from the sale of ideas and knowledge.

Amazon’s Jeff Bezos is the richest man on the planet. Every nine seconds, Bezos makes the median salary at Amazon. He might soon be the first trillionaire. His workers, meanwhile, collapse from exhaustion at their posts.

Income and wealth inequality are at extraordinary levels. A study by the Economic Policy Institute — called “The New Gilded Age” — shows that income inequality is at levels not seen in the United States since the Great Depression of 1928. The costs of that inequality are borne on the backs of the working class — people who struggle with debt at every turn. Merely a third of Americans have enough money saved for a $1,000 emergency room visit or for the repair of their car. Boots gets under the skin of that debt. It frames his film. It — in the absence of worker power — constrains the imagination, forces ethics to go out of the window, strains the basic bonds of human fellowship.

You have to hate capitalism if you are able to mirror its violence. Otherwise you’ll just end up forgiving it, blaming individuals for their failures, setting the cat amongst the pigeons of human follies. But Boots is immune. He has read his Marx (“Presto, read the Communist Manifesto,” is the first line of the first song from The Coup’s first album — it sets the tone). The first English translation of the “Communist Manifesto” read, “A frightful hobgoblin stalks throughout Europe. We are haunted by a ghost, the ghost of Communism.” There are demons inside the system, devilish ways in which good people are forced to become terrible people. Marx got that. Boots gets it. Otherwise you just apologize for the misery.

“We goin’ stop the world, make all you motherf*ckers jump off.”

Revolution isn’t pretty. But it takes a long time to get there. Boots’ world is Oakland, a town of misery and revolutionary instinct. This is the home of the Black Panther Party and of the militant dockworkers. These dockworkers routinely join anti-racist and immigrant rights groups to fight for the rights of political prisoners such as Mumia Abu-Jamal and against the racist immigration policy of the United States. It is as likely that they’d shut the Port of Oakland — a node in the global commodity chain — for their own wages as for the deeper questions of human freedom. You can’t think of Oakland without the raised fist.

It does not take long for “Sorry to Bother You” to find its way to the American Left. Boots knows his history. The Left is capacious. The main organizer here is an Asian-American man who organized a sign holders’ union in Los Angeles before he found himself organizing the telemarketers of Oakland. The rebellion in the telemarketers shop is a rebellion of this multi-ethnic working-class, where solidarity is crafted through anger and affection. It is class that binds them, even though their journey to solidarity starts in so many different places.

The film would have been stronger with more women in the lead — as women are in the lead in the political movements inside the service sector. Women seem to be in the majority at the picket line, which is a fierce battle against the ruthless security services. The violence is unvarnished. A few years ago, the City of Oakland had to pay the Occupy protesters $1 million in damages in recompense for the brutality of the police. Imagine a cameo in the film from Cat Brooks, co-founder of the Anti Police-Terror Project and candidate for mayor of Oakland.

Capitalism has a problem. It produces its own gravediggers. Marx identified the agent of history as the proletariat, the workers who own no capital but produce it for the capitalists. It is one of the uncontrollable urges of the capitalists to produce more productive workers, workers who have no leisure and only energy. The capitalist in Boots’ film has produced these workers. They are equisapiens. There is no “magical realism” here. This is our reality. Workers are attached to machines, pumped with drugs (including the soft drug of caffeine) and set to work — cyborgs of the 21st century. Having produced these workers, these equisapiens and cyborgs, the capitalist is at their mercy. They get too strong. They lead us into a world in which “the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all” (“Communist Manifesto”). They are the ghosts of our future, neighing for us to follow them.