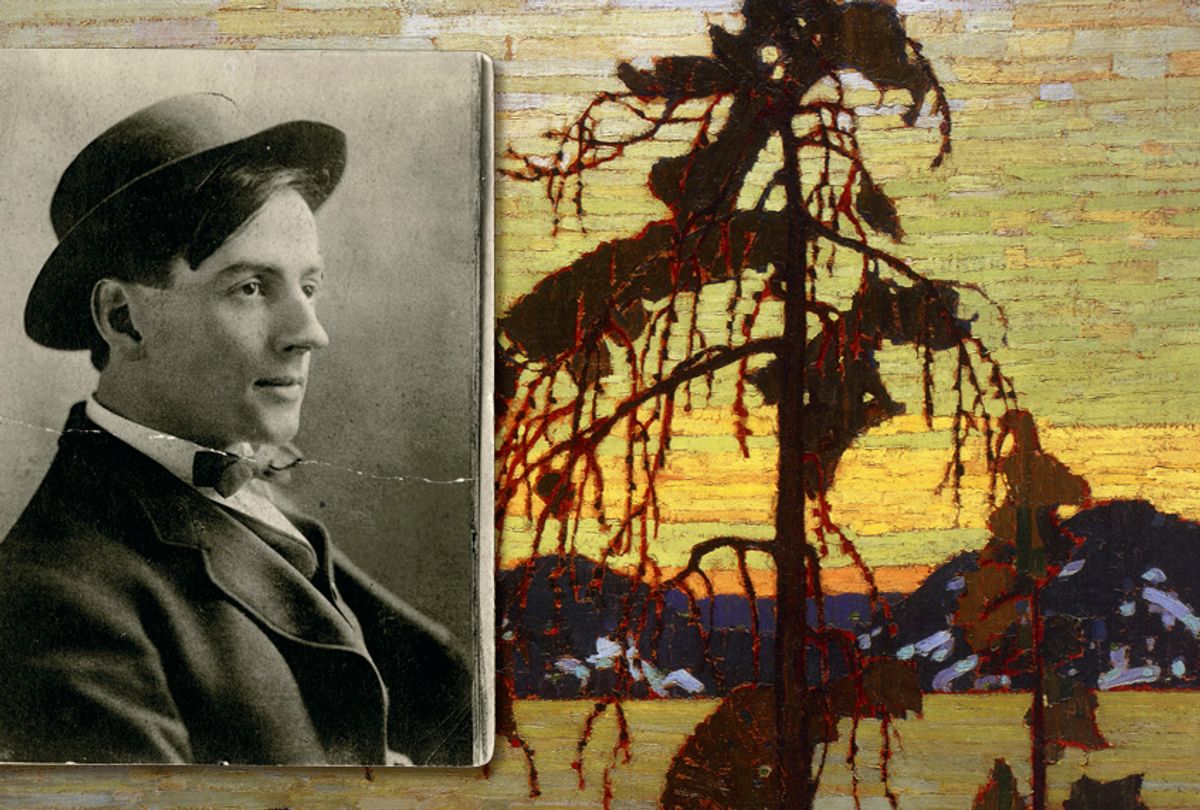

Tom Thomson may not have been Canada’s first artist, but he was certainly the first artist that Canadians rallied behind as representing the art of their country. The artist was virtually unknown during his lifetime. But the fact that he died young (age thirty-nine) in a remote wilderness lake under circumstances that were never fully explained, brought an intrigue to the artist and his work that resulted in a rapid rise in his popularity. How the artist met his death has been the subject of an ongoing controversy ever since his lifeless body first bobbed to the surface of Canoe Lake in July of 1917. The story has been particularly gripping from my perspective, as my father, Bill Little, was one of the four men who discovered the Canoe Lake skeleton in 1956. Consequently, I grew up with the Tom Thomson mystery as a constant companion. An odd way to spend one’s youth admittedly, but doing so brought me to my present-day vantage point on the story, along with amassing a wealth of facts surrounding Thomson’s death, burial, and alleged reburial. What has finally come to light is a story of jealousies, sexual infidelity, alcohol, homicide, and cover ups. It is a Canadian story to be certain, but more than that, it is an all too human story that could have played out anywhere at almost any time.

Goldwyn Howland, a medical doctor and professor of Neurology at the University of Toronto, had awakened early on the morning of July 16, 1917 in a small cottage that he had rented on Statten’s Island. Statten’s Island (now known as Little Wapomeo Island) is a small island, situated near the northwestern shore of Canoe Lake, which had originally been leased from the government by Taylor Statten, a man employed by the national YMCA as the Boy’s Work Secretary, but who was away that month at a YMCA training school in Massachusetts. Howland had arrived in the park only the night before, bringing with him his young daughter, Margaret. The pair had been looking forward to some father and daughter time together over the coming week and had already enjoyed a little fishing and canoeing on the evening of their arrival. Above all for the good doctor, he had been most welcoming of the kind of mental relaxation that being in a rural environment had always seemed to induce. On this particular morning he decided to let his daughter sleep in; there would be no shortage of outdoor things to do once she awoke and these, combined with the fresh air and sunlight, would tire her out quick enough. Not wanting to disturb her slumber, Howland stepped outside onto the small veranda at the front of the little cottage and was immediately taken with the splendor of his new surroundings. Having arrived the evening before, he hadn’t had the opportunity yet to see the sights of the lake in the morning sunlight. His view from the front door allowed him to take in all the northern section of Canoe Lake and, although it was still early, the sun was already beginning to shine brightly through a cloudless sky. Looking several hundred yards to his right he could see what is now called Wapomeo Island, and looking directly across the lake from the cabin he could spy Hayhurst Point, a small isthmus that cuts into the northern portion of Canoe Lake. While it featured a steep rock face, there was a trail that led to the top that would afford a tremendous view of the lake. Yes, that might be a good spot for he and his daughter to visit today. The doctor sat down on the steps next to the front door of the cabin, content in the thought that it was shaping up to be a great day. And then it happened.

He had been looking toward a point of land just west of Wapomeo Island when suddenly something broke the placidness of the lake’s surface. The object appeared to be about 400 yards away and immediately caught the doctor’s attention. It looked too big to be a loon, and far too motionless to be an otter or a beaver. Even more peculiar was the fact that, whatever it was, it hadn’t moved since it came to the surface of the lake. Howland strained his eyes to make out what the object might be. There were intermittent flashes of color, flecks of brown and gray, which revealed themselves in between the crests and troughs of the waves—but the object was too far away for him to make out its true identity with any degree of precision. Intrigued, Howland walked down to the shoreline of the island for a closer look. The extra thirty yards he gained from doing so did nothing to bring the object more clearly into focus. He shrugged his shoulders and walked about the shoreline for a bit, looking at the natural beauty that surrounded him from different points on the little island, but every now and then taking a look back at the object that still hadn’t moved in the water.

As the doctor was just about to return to the cabin his peripheral vision picked up on something else: two men in a canoe paddling south down the center of the lake. The men were the local guides George Rowe and Lowrey Dickson and, from the doctor’s vantage point, they appeared to be heading in a direction that would eventually bring them within a hundred feet or so of the object. It occurred to the doctor that if he could hail these men they would be able to make a positive identification of the bobbing object, and thus settle what had now become a gnawing curiosity for the physician. Howland quickly walked out to the end of a small dock that jutted some twenty feet out from the island and called out to the men to secure their attention. Upon hearing a voice, both guides lifted their paddles from the water and looked in the direction that the sound was coming from. Once the doctor had secured their attention he pointed toward the object that was still bobbing in the water and asked if they would take a look at it for him.

“Sure thing!” Dickson replied, and then tapping his partner on the back with his paddle, said, “Probably a loon.” Rowe wasn’t sure if Dickson was talking about the man on the dock that was yelling and waving his arms, or the object that he just now spied floating in the water about 300 yards southwest of them. Dickson had also spotted it, and the guides presently decided to change their course to move in and investigate.

It wasn’t long before both men realized that the object they were closing in on was definitely not a loon; however, they were not yet close enough to rule out its being a dead animal. Animal carcasses floating in the lake were certainly not unusual, particularly when the ice melted in the spring. But this was mid-summer, which would make such an occurrence something of a rarity. As the bow of the guides’ canoe continued to cut through the water, the object that lay before them slowly began to come more clearly into focus and, as it did, a sense of uneasiness began to rise in both men. Rowe, the man in the bow, would have been the first to discern that the object they were approaching was clearly clothing of some sort—grayish in color—perhaps someone’s laundry had blown into the lake from one of the cottage clotheslines. But as the canoe verged nearer he would have discerned that this article of clothing also had hair. And as they drew closer they would have observed something bluish gray in color protruding from beneath the clothing that looked like a human hand. It would now have been evident to both men that the object that they were rapidly closing in on was not some cottager’s wayward laundry but rather a human body—but whose body? In 1917 the population in the Canoe Lake region was small, perhaps thirty to forty people year-round, and everybody knew each other well. The only person who had been reported missing was the seasonal resident and part time guide, Tom Thomson—but that was eight days ago and everybody believed he had been lost or stranded in the woods. Indeed, the woodland was where all of the search parties had concentrated their efforts when attempting to locate him.

READ MORE: An orca has been carrying her dead calf for 10 days. What does this mean?

The guides ceased their paddling and allowed their canoe to glide in alongside the body. One can only hope that the corpse was floating face down as its state of decomposition would have been startling. Later reports indicated that the putrefaction had advanced to the point where the flesh was detaching from its hands and the limbs and face were severely swollen. While it’s likely that both men would have suspected the identity of the body that they now found themselves looking down upon, its condition was such that making a positive identification would have proven difficult.

Both of the guides had known Thomson well. Indeed, the three had gotten together to have a few drinks and play some cards only nine days prior at Rowe’s cabin. Rowe had also been Thomson’s guiding partner on several occasions when the pair had taken tourists out from Mowat Lodge for an afternoon of fishing and sight seeing. But the object that Rowe was looking at presently didn’t look anything at all like the man he had partied and guided with. Visions of Thomson, and of the clothes that he typically wore on those occasions, now began to trickle through the old guide’s consciousness, bringing with them the grim realization that Tom Thomson was dead. Rowe turned around from his position in the bow of the canoe to face Dickson, and witnessed a look of silent anguish on his friend’s face.

“What is it?” yelled Dr. Howland from the end of the dock.

He received no reply from either man.

“What is it?” he yelled again, the urgency in his voice snapping both Dickson and Rowe from their reverie.

“It’s a man!” yelled Rowe. “It’s Tom Thomson!”

The name meant nothing to Howland. But a dead body floating less than five hundred yards from where both he and his daughter were vacationing was certainly a cause for alarm. The body had to be removed from its proximity to the island.

“Do you have a rope?” he yelled.

Rowe looked puzzled. “What do you want us to do with it?”

There was no way Howland wanted the corpse brought to the little island that he and (particularly) his daughter were presently occupying. He quickly scanned the horizon for the next nearest point of land from where the body was floating. An outcropping of shore, about five hundred and thirty-eight yards due south, would make do for the time being.

“Tie your rope around the body and tow it over to shore!” Howland yelled, gesturing toward a point of land that would come in time to be called Gillender’s Point, named after Hannah Gillender, from England, who would purchase the property in 1925 with her friend Annie Krantz from Philadelphia. But that was still eight years away; in 1917 the small point sat empty and was unnamed. The doctor then yelled to the men to leave the body in the water once they reached the shore, as removing it would only accelerate its rate of decomposition.

An apocryphal story that has endured throughout the years has it that when the doctor and his daughter had gone out onto the lake for a little fishing on the evening they had first arrived at Canoe Lake, Margaret had snagged her fishing line on something, and, after attempting to free her line to no avail, her father had simply cut it loose from the object it was snagged on, and the two had paddled back to the island. The object that the daughter was believed to have snagged her line on was later presumed to have been the body of Tom Thomson, as the body would be spotted the next day floating in and around the very location where she had caught her line the night before. This may be one of those rare occasions when an apocryphal story turns out to be true, as when my father asked Dr. Howland’s daughter Margaret about this anecdote many years later she replied that this did indeed describe the situation as she remembered it.

Upon reaching Gillender’s Point the guides paddled into an area that was sheltered by large stones and tree stumps. Quickly scanning the shoreline, they spotted a large tree that had toppled into the water from the shore, a portion of its trunk lay submerged in the water with some of its gnarled branches jutting upward into the air. One of these branches would suffice as a temporary hitching post of sorts, allowing the guides to release the end of the rope that had been tied into their canoe and secure it to the tree branch. The other end of the rope would remain firmly attached to Thomson’s corpse, thus securing the already rather fragile body in the shallow waters. The guides knew without the doctor telling them that their next step would be to notify the authorities, which, in the Canoe Lake area, was the Algonquin Park Ranger Mark Robinson.

Robinson had been a park ranger since 1907, save for a brief absence in 1915-1916 when he had been overseas fighting in World War I. There he had been an officer with the rank of major, had been wounded, and subsequently discharged. In the spring of 1917 it was a considerably frailer Mark Robinson who found himself back in Algonquin Provincial Park. He was now fifty years old, still fit and capable, but the war and his injury had weakened him considerably. Nevertheless, Robinson had returned to his duties as if he had never been away, these included overseeing the influx of tourists that came and went by train at both the Canoe Lake and neighboring Joe Lake stations, as well as making specific rounds at various points throughout the park to check for poachers.

Robinson was a naturalist and an expert canoeist, and he and Thomson had developed a mutual respect over the past several years that they had known each other. Whenever the artist had a question about where to find a particular type of tree or what season a specific color would be predominant in the park, it was Robinson’s council that he sought. And when Thomson had first been reported missing it was Robinson who had led the search parties to look for him. Thomson had been more than just a seasonal park resident to the ranger; he had been a friend and, consequently, breaking the news to him would not be something either of the guides was looking forward to.

The shoreline where the guides had beached their canoe and out from which Thomson’s body had been moored, lay several hundred yards to the south of several cottages and Mowat Lodge, an inn for tourists that was located just off the northwestern shore of Canoe Lake. Word of the discovery had by this time travelled back to the lodge and, at some point, Charlie Scrim, a part-time guide who had been staying at the lodge and who had also been a friend of Thomson’s, had either volunteered or had been dispatched to inform Mark Robinson of the morning’s discovery. Further learning of the news that morning were the summer cottagers Martin Blecher Junior and his neighbor, Hugh Trainor, and shortly thereafter the pair had hopped into Blecher’s motorboat and headed over to the point of land where the guides were now safeguarding the body.

After about a twenty-minute paddle north along Joe Creek, Charlie Scrim had reached the Joe Lake Dam. Here he pulled his canoe from the water and carried it on his shoulders along a short path that led to the Joe Lake Narrows, a small basin of water that lay just above the dam. He placed his canoe back into the water and made a beeline to Mark Robinson’s cabin. The ranger’s cabin was situated on the northeast corner of this small body of water and just south of the Grand Trunk Railway tracks, which ran atop the bank that separated the narrows from Joe Lake. When Scrim reached the ranger shelter house that was Mark Robinson’s home he quickly beached his canoe and, without bothering to knock, charged into the ranger’s cabin. Tears were streaming down his cheeks.

“They found Tom’s body!” Scrim exclaimed.

“What?” Robinson asked, incredulously.

Scrim repeated his statement and then provided what details he knew about the morning’s discovery. The ranger felt as if he had just been kicked in the stomach—hard. He had worked himself almost to the point of exhaustion over the past week, walking and canoeing all around the Canoe Lake region in the hope of locating the missing artist. The news from Scrim had, in an instant, revealed that his labor had been for naught.

Shares