The legendary punk band from Michigan, the MC5, garnered fame in the late ‘60s for playing outside at the 1968 Democratic Convention, which then devolved into a riot. The MC5 rose to prominence during a stressful time in American history, the late ‘60s, with Richard Nixon in power and the Vietnam War in full force.

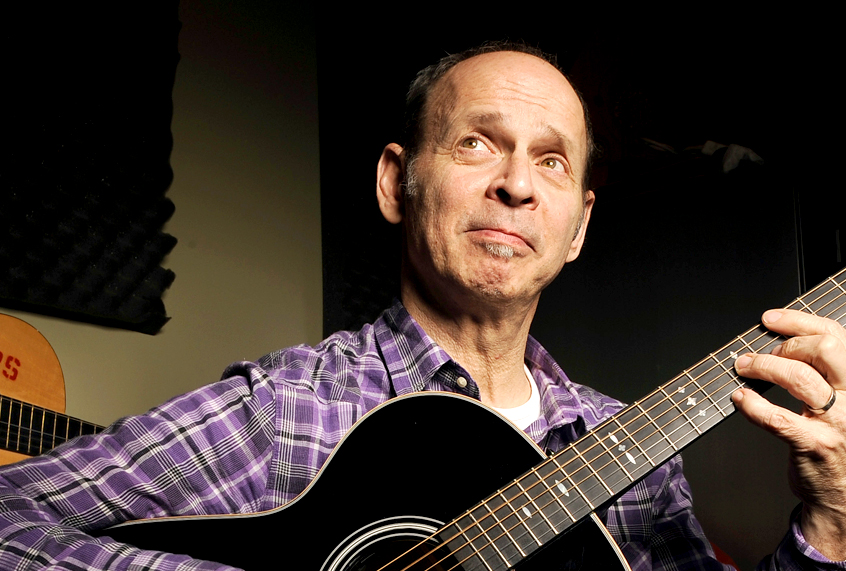

Fifty years later, founding member and guitarist Wayne Kramer is still calling for a revolution, now with a new memoir, “The Hard Stuff: Dope, Crime, The MC5 & My Life of Impossibilities.”

Kramer sat down with me for “Salon Talks” recently to discuss the parallels between the tumultuous 1960s and now.

Watch our full interview

“Salon Talks” with Wayne Kramer

The MC5 came to prominence in the late ’60s and garnered legendary status for playing outside the 1968 Democratic Convention, a show that developed into a riot. That was a hugely stressful time in American history. I want to ask you, do you see parallels between then and now? How so?

I do. It’s not the same. The things that the baby boomers achieved in my generation in the ’60s — ending the war in Vietnam, moving civil rights forward, addressing outdated sexual morals, this kind of ’50s sexuality, marijuana — those things are different today. But you’re right. There are some disturbing parallels. We have a wretched grifter in the Oval Office, who has utter contempt for the rule of law and it tries to manipulate the political process to his own ends, very much like Richard Nixon. We have corruption that’s stunning in its wealth and breath from the high offices of Congress down to the local dog catcher. I mean, the corruption that exists in the establishment is mind boggling, we really clock it.

We have a war ongoing for 17 years in the Middle East against the people that actually are no threat to the United States of America. We have a completely incoherent policy. I mean, this is exactly what Dwight Eisenhower warned us about, this military industrial complex of politicians, generals, and arms manufacturers that, if encouraged in and allowed to be left to their own devices, would create perpetual war. We have that going on as well.

On one hand, I think, I mean you’ve probably heard of this idea of the American politics swings five degrees to the left to the right, and we swung over to the left with the election of Barack Obama, who was a constitutional scholar. He lived around the world. He was a wise man. He knew how to govern and he was about public service. Then, we swung the other direction and the pendulum broke off the clock and the clock was smashed on the floor and we ended up with this developer that we have. At this point, I’m just looking for the swing back.

Well, maybe in a few months.

Yes. There’s still hope.

That’s an interesting question. You bring up the war in Afghanistan. I feel l like for your generation, the Vietnam War was this extremely pressing issue in politics constantly, and it drove a lot of your activism in the ’60s. Why do you think that just is on such a back burner now?

Well, conscription is probably the first the answer to that question because young men were required to join the military and go off to fight and die. Most Americans of my generation could not justify what was happening in Vietnam. I mean, that’s why there were hundreds of thousands of people demonstrating. That’s why it stopped, because it was a military adventure that went sideways. A perfect storm where everything went wrong and we just sent more young people over there to the tragic end . . . over 50,000 young American lost their lives over there for no reason in the end. We can look back in history now and we can see clearly. I’m not dogging the warriors. These were guys that believed in what they were doing. They’ve made the ultimate sacrifice and how we treated them has been horrific. Vietnam vets are leaving Los Angeles and it seems half the people have lived outdoors are Vietnam vets.

Today, there’s no conscription and the American public is not being charged for this war. They’re not even paying for it. They’ve no skin in the game. We’re charging our kids for this war. Everybody kind of [acts like] “let’s go to the mall, man. Have you got a new iPhone?” It doesn’t affect them. A lot of rural families, their children go, or families that have generations of military people, they go, and young men will always want to go to war. I used to think it had something to do with politics. It doesn’t. This is an ancient ritual for young men to see if, can I go and walk through the fire? Can I do this? Young guys go over there and of course we know they come back profoundly damaged. They commit suicide at a horrific rate. There’s no coherent policy as to why we do this.

In your new memoir, you write about this, you struggled with drug addiction for a long time and during an era when there was, I think, not as much sympathy for people with addictions. I think now there’s a little bit more awareness of how it’s a disease and a little bit more sympathy. I want to ask you, how you think especially in this present moment we can move forward better to help more people that have this problem?

Well, decriminalization would be the first step, to remove this from a police issue at all. This is not a justice-crime issue. This is a medical, psychological problem. If we look at the model that the Swiss have instituted. Twenty years ago, the Swiss had a horrific opiate problem. Tourists couldn’t go to a city park in cities in Switzerland because the junkies were all nodding out, puking, shooting up in the middle of the day. And the Swiss being the conservative, focused people that they are, [said] we got to do something about these, let’s call some experts in. They call the experts in and the experts said, legalize this, control it, put it in a clinic, make treatment available on demand. They did.

There is no heroin problem in Switzerland. They have legal clinics where people that are addicted to opiates can go and get the medication they need every day. The average stay in those clinics is three years. The first year, they stabilize their medical addiction. By the second year, they can get a job. They can get a boyfriend or a girlfriend. They can start to have friendships. They can start to show up for real life. By the third year, going to the clinic everyday can be pain in the ass. They want to get done with it.

This could work in this country. If this was focused on harm reduction and treatment, we could find a reasonable and successful policy for addiction. We haven’t got there yet. I mean, the war on drugs — the drug prohibition killed more people than drugs ever could and destroyed more families. In America today, we have 2.3 million of our citizens under lock and key in prison. I’m an archetype of a drug war prisoner. I served a prison term in the 1970s for a non-violent drug offense. I think it’s the greatest failure of social policy in America’s domestic history.

I think you’ve been speaking out for about this issue and it’s an issue that I feel you’re starting to hear more people talk about in the public discourse. You’ve seen both Democrats and Republicans, a handful of Republicans, even start to say, “We should do more to reduce mass incarceration and get people back to real life.” Do you feel optimistic that this is possible in the future? Soon?

Yes. My attitude is people made this mess and if people made the mess, people can fix the mess. But we’re up against the formidable challenge. First, this is a gigantic business hit. People say the prison’s systems broken. It’s not broken, it’s a big hit. It’s a huge success. It’s a $90 billion a year industry. That’s a tough one in our fine, fine capitalist world that we live in. That’s a tough one to undo. I’m suspicious of the Koch brothers and others that on the right that champion rehabilitation, re-entry, repurposing justice dollars. Those are all good things and they need to happen.

But what they do is they might cut a break to the non-serious offender, the non-violent defender, the non-sexual offender, and they want to reduce those sentences. But while they’re reducing those people sentences, the serious offender, the sex offender, the violent offender, their sentences go up. Really, this is so far just been a whack-a-mole kind of thing. The worst part of it is that no matter what changes we make and if we do succeed in making sentencing more sensible and lower our prison population, that’s just clearing out cells for immigrants, and they want to keep those jails full and keep those prisons full because they make just as much money on immigrants and immigrants have no rights. You and I go to prison; we still have habeas corpus. We can talk to the press. We can talk to our families. We can have an attorney. Immigrants have none of that. I’m a little skeptical when I hear the Koch brothers talking about prisoner forum. Underneath it all what they really want is there’s a couple of aspects of the white collar crime laws that they want to undo to further their own economic benefit.

READ MORE: Honoring Aretha Franklin, “Queen of Soul,” the greatest singer of our time

This is an important warning. I can talk about this all day with you, but we should ask about music and about the MC5. It seems to me in the ’60s especially music was very essential to progressive organizing. You guys were huge on the left. There were a lot of rock bands that were talking about the war and about social progress. R&B bands were essential to the civil rights movement. What do you think music can add to social justice movements? Why is it so important?

It’s our drumbeat. This tribe over here beats the drums and they tell the tribe over there what’s happening in their neighborhood. In the songs, a community is warned. If you have a Bob Dylan song, it really just kills you, and I love that song too, we meet in that song. There’s a unity for us in that song. That’s the role that music is traditionally played in a political change and social change. We’re the messengers. We sound the alarm.

We inspire people, hopefully. We energize them to go out and get involved in the process of democracy.

I think that’s been ongoing since then, but do you have advice to young people that want to combine music and politics in this way?

Well, yes. I’d say start were you are. Start in your family. Start at the dinner table. See if you can convince somebody to see things your way using reason, logic, facts, the truth. Start with your friends. Can you have a conversation with them about something that’s important to you in your neighborhood? In your city? Are you involved in local elections? Do you know who your local judges are? Do you know who your representatives are? Do you know how they feel about things? Do you agree with them? If you don’t agree with them, elect somebody else. Get involved. Democracy is not a concept or a word, or a thing to talk about, it’s a thing to do. I don’t mean hitting a like on your computer. I mean, getting your ass up off the couch and go out meet some people and get organized and take action that affects the world around us. That affects our communities and our states and our nation and our civilization.

I think one good thing [to come from] Donald Trump’s election was that you’ve actually seen people in the streets so much these days. Do you think that helps?

I’m not sure. I mean, look at right after the election, the Women’s March, that was unprecedented in history. That was a massive demonstration. Did it affect Trump? He didn’t pay any attention to it. Didn’t moved him one degree. I think the authorities have learned lessons of the ’60s as far as street demonstrations go. They can handle it. They control it. They control the news. When the war in Iraq was gearing up, the LA Times said there were 30,000 people in the street. I was out there — there were 300,000 people in the street. I’m not saying there’s a conspiracy and the newspapers are working with the government. I’m just saying that the police and the government can handle street demonstrations.

I joined Rage Against the Machine for a performance at Kick Out the Jams at the Democratic Convention 10 years ago in Denver and we had a march — a bunch of GIs, veterans, and regular people — and they had a marching route for us. They routed us right through the industrial section of town where nobody lived and we’re marching and everybody shouting and they got their phrases, “hell no, we don’t, and these are our brothers, these are our sisters. We’re resisters.” There’s nobody. We’re just hearing it out for ourselves. They march us all around town through these industrial neighborhoods. Then, they finally dumped us out in a football field just completely fenced in.

Yes.

They know how to handle street demonstrations. I think, they’re not negative. They don’t hurt anything. It’s good for people to go and demonstrate in these kinds. I think that recent event in D.C. where the white nationalists were going to have this year’s whatever they call it, “Unite the Right” and then like 10,000 people came out to oppose it. That was pretty good. I like that because that was very focused and that carried a clear message. But in general, I think we have to find some other routes to bring pressure on legislators on political people. I mean, this is Saul Alinsky 101.

That makes a lot of sense. Obviously back in the ’60s, it rattled Nixon. It rattled Johnson.

It was a big thing to see 100,000, 200,000 people marching in Washington, or in Detroit — it was meaningful. I think they can handle it these days. I don’t think it shakes them that much [now]. You can shake them in a vote much better. Much more effectively.

I have one last question for you. So much great rock music from the ’60s and ’70s comes from the Midwest. You guys, the MC5; the Stooges; Divas, one of my favorite bands of all time —

Mine too. Yes.

Why do you think the Michigan-Ohio area was such a hotbed of musical innovation at that time?

Because we weren’t hip. We weren’t cool. The industrial in Midwest, like nothing cool could happen in Akron, Ohio or Detroit, Michigan. I mean, they make cars there. My sense was the things we were exposed to, the music that inspired us, the Free Jazz movement, the music of John Coltrane and Sun Ra, and for me to try to do what those guys were doing with electric guitars and this rock band, we felt like “Geez, our ideas are as good as anybody else ideas. Maybe even better. Maybe even more stretched out than this stuff I’m hearing from the West Coast, or from New York, or from London.”

Because the world kind of looked down on us, it gave us an attitude. We pushed harder. We became more assertive or aggressive even, and we had to fight a little harder to make some noise and be part of the conversation. It’s like . . . if you have a five-year-old as I do, and you tell him don’t do that, the first things he’s going to do is do it harder. It’s limit testing.