The ominous sound of doom emanates out of a heartbeat, distorted guitar, and film noir saxophone. An urgent and deep voice warns,

These men who hunt us

Know nothing of our lives

So please step lightly

There’s menace in the heavens

Dark and threatening

There’s a shadow in the air

They’re closing in

They’re closing in

Just a few moments later — the threat grinding into bones with each siren shriek of the guitar — the same voice rises to shout, “Hey, Hey c’mon / I need you more than ever / Hey, Hey c’mon / We’re running for our lives.”

An orchestral swell of strings begins to overtake the sonic orgy. The voice, even as it becomes more emphatic in its plea for mercy and delivery, struggles for an ear — unable to compete with the symphonic cacophony. “There’s refuge in your heartbeat,” it manages to declare.

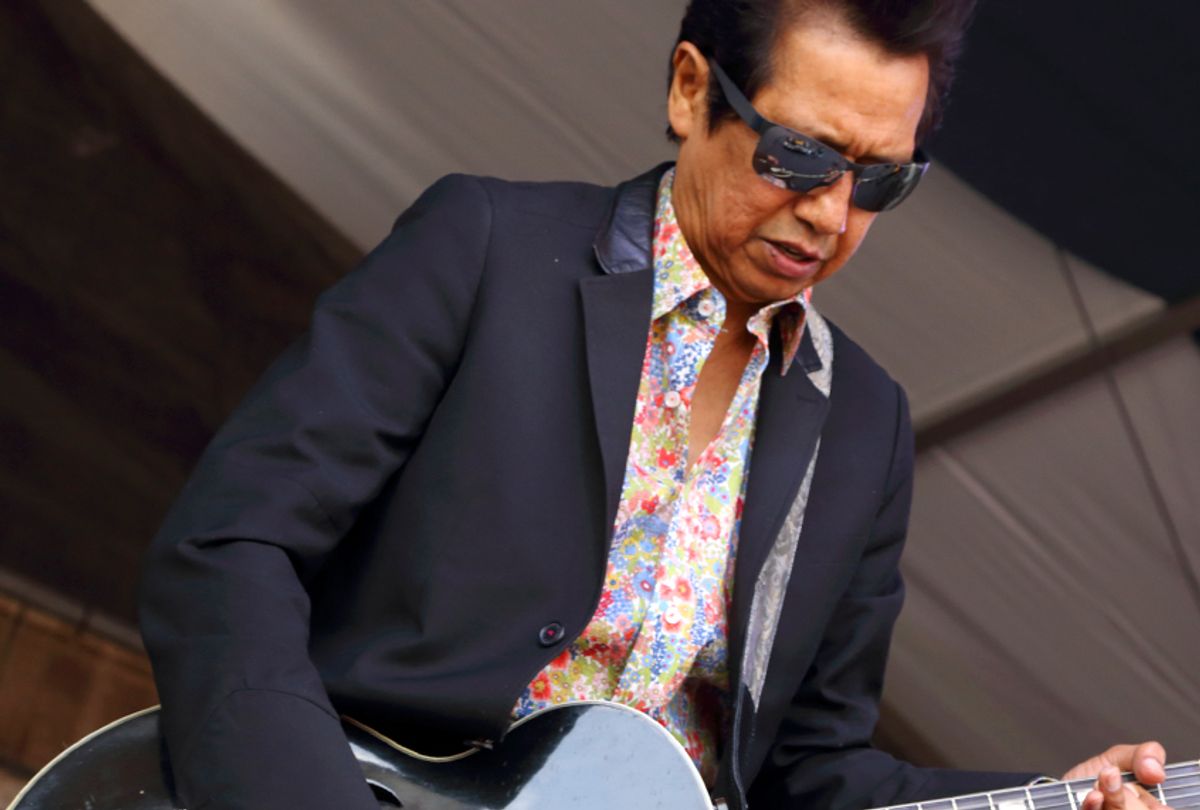

“Footsteps in the Shadows,” is the opening song of Alejandro Escovedo’s new concept record, “The Crossing.” One of America’s great singer/songwriters, who No Depression magazine named “artist of the decade in the 1990s, has created a timely confrontation with the nativist mood of America, but also a timeless documentation of the insatiable hunger driving migrants on epic journeys to foreign soil throughout the history of humanity.

READ MORE: The Beatles’ struggle to finish “The White Album”: How bad did it get?

“The Crossing” combines robust and rollicking rock and roll with the beauty of a symphony to narrate the lives of two immigrant boys suffering and triumphing as they search for life and liberty in the United States. One is from Mexico, and on one song he demonstrates awareness about how too many of his neighbors view his presence: “They call us rapists / So they build a bigger wall . . . ”

The other boy is from Italy, and he serves as a reminder of the obvious, but often forgotten reality of American life: Unless your ancestors were already here when the Pilgrims made their arrival, or came to the country in chains, your family history is one of immigration.

It is always a risk to talk about art as instruction, especially rock music. From the swing of Elvis Presley’s hips to the funky cry of Hendrix’s guitar, rock and roll is, first and foremost, a physical stimulant. Bob Dylan injected the intellect into the artform, catalyzing the eventual synthesis that one of his acolytes, Bruce Springsteen, described with perfection: “Rock and roll should come in through your loins, travel through your heart, and leave through your head.”

Escovedo aspires to activate the body and the soul on his new record, and with a searing combination of imagination and gusto, manages to succeed. When I talked to him about “The Crossing,” the conversation replicated the balancing act of the music. Discussion of songwriting and performing took place with the background of America’s heartless and mindless new immigration policy, while rumination on politics inevitably led back to song.

“The music has to stand up on its own, as something that people can play and enjoy many years from now,” Escovedo said. “Art, I believe, has the ability to connect with people, and move them, and even make them think. In telling human stories you allow people to relate to you much more than giving a straight up, political didactic. In telling the stories of these two boys, we told the story of not only immigration, but also the loss of home, the loss of innocence, and of any kind of immigrant who crosses a border.”

Escovedo has made a career out of crossing musical borders, from rock and roll to country, a leader of the Americana genre, experimenting with classical influences and Latin innovations, his catalogue is wildly unpredictable, and as a consequence, never boring. “The Crossing” achieves symbiosis with its lyrical story of immigration and its open borders musical policy.

“Lou Reed was a fly on the wall when we made this record,” Escovedo said in reference to the importance of Reed’s solo record, “Street Hassle,” and the work of the Velvet Underground, on “The Crossing.” The beautiful and brutal blend of distorted guitars and strings — at times combative and others, cooperative — is the perfect complement for the highs, lows, and mixed emotions of the lyrics.

Escovedo recorded the album not in his hometown — the musical hotbed of Austin, Texas – or Reed’s New York — the home of Ellis Island – but in Emilia-Romagna, Italy with the Italian backup band, Don Antonio. Antonio Gramienteri, Don Antonio’s guitarist and leader, co-wrote all of the songs.

“In addition to all of the things that I mentioned earlier, The Crossing also tells the story of Antonio and I,” Escovedo explained, “There are things that as I get older, I’ve had to leave behind. The Stooges don’t exist anymore, rock and roll, the way that I knew it, doesn’t exist anymore, the people who I looked up to as great teachers, are all gone.”

In one of the record’s standout songs, “Outlaw for You,” a playful and cocky rocker for a Latino carnival, Escovedo announces, “I’ll be an outlaw for you,” directly invoking the names of Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, Cesar Chavez, Gregorio Cortez, and Octavio Pa.

Through their admiration of rock and roll and the art of rebellion, Escovedo and Gramienteri forged a bond. The kinship of Italian culture to Mexican culture also enabled Escovedo to fully explore the Latin influence on his own music: “The Italians brought out more of the Latin in my music than any other band I’ve played with. There is something about their gift for melody, and their understanding of the romantic, that connected with me.”

As much as the record celebrates the energy of cross-cultural creativity, and the inspiration of musical, political, and literary icons who resisted every enticement toward conformity, it is also elegiac.

“The boys have a sense that they got here too late. Maybe the America they were hoping to find doesn’t exist anymore,” Escovedo said.

“Sonica USA,” the most straight-no-chaser throwback of rock and roll on the record, resembles an early Stones song, and expertly deals with the pull of America’s cultural power — the promise of personal expression with the amplification of transgressive music and glamorous movies. It was the soft diplomacy of jazz, rock and roll, Hollywood, and blue jeans that turned Soviet youth against the shackles of communism — not the advancement of the US military or maudlin and self-serving speeches from Ronald Reagan - and with the addition of hip hop, it is that same artistic energy that animates many people’s excitement for America, even as it descends into a fascistic parody of its former self.

“Little Johnny digs the MC5,” Escovedo sings, “Cypress Hill and the Jurassic 5 / Saw The Plugz at Larchmont Hall / This is the America / I want it all / Feel the power / Peoples parade / Sonica USA.”

Not only is there a deadly contrast between American soft and hard power — between the vision of the country accessible through art and the unforgiving slap against the pavement of on-the-ground reality — but there is also the worry that, through its materialistic excesses, America has undermined its greatest cultural resource.

“I grew up in the ‘60s,” Escovedo recalled, “and it was an era when music, poetry, literature, film was all finding a new voice. It was humanistic expression, and behind that, we as practitioners of a new lifestyle felt that music was our voice. It was going to help change the world, and make it a better place. Then, the disappointment came with the opposition to the lifespan that that movement had. It began in the 1970s, and worsened in the ‘80s. People who were artists and revolutionaries suddenly became entrepreneurs, and became more interested in the stock market. We not only lost a lot of people, but it softened the culture.”

A softening of the culture has led to general atrophy of democratic muscle. Democracy is not for the weak, but for those sufficiently strong and secure to understand that difference is not synonymous with deficient, and that citizenship within a democratic state and culture demands an investment of time, energy, and labor.

Alejandro Escovedo, with his new record, has not only created an entertaining work of rock and roll, but a tribute to the resistance and combative artistry necessary to maintain the democratic spirit. “The Crossing” is a counterargument to every easy, but insidious impulse responsible for the softening of America’s democratic culture into xenophobia and the easy temptation of a reality television star turned autocrat.

The record ends with appropriate beauty and melancholy. Its closing song, “The Hesitation,” begins with the soft picking of an electric guitar, which eventually opens space for a mournful saxophone and the opening lines, “It seems the times have changed / They’ve broken all the pretty things . . ."

It seems like a melancholic reflection on the extinguishment of the America promise of pluralism and progress toward the steady enlargement of freedom, and while it certainly offers grief in the cemetery of the country’s better days, it suddenly transforms into an even grander meditation on the endlessly spinning wheel of life’s generosity, banality, and cruelty.

Thoughts and prayers never last

Don’t waste them on the past

We all become history

When we make the crossing

Escovedo softly speaks the final lines, and with subtle grace, provides powerful emphasis to his ultimate, in every sense of the word, idea for musical emphasis. Cynics might call it a cliché, but what every human being shares has greater power and value than the details of demography that divide us into categories.

With “The Crossing,” Alejandro Esovedo, drawing on American rock and roll, Latino influence, and Italian romance, is forcing everyone within earshot to consider whether we still have the courage to live according to that most universal and ancient truth.

Shares