It started with a headache.

Fabrizio Stabile noticed it while he was mowing the lawn on an ordinary Sunday afternoon in New Jersey. The headache prompted Stabile to take some medicine, lie down, and sleep through the night. But when he woke up on Monday morning, the headache persisted. Later in the afternoon, he could not speak coherently nor could he get himself out of bed. His mother called 911.

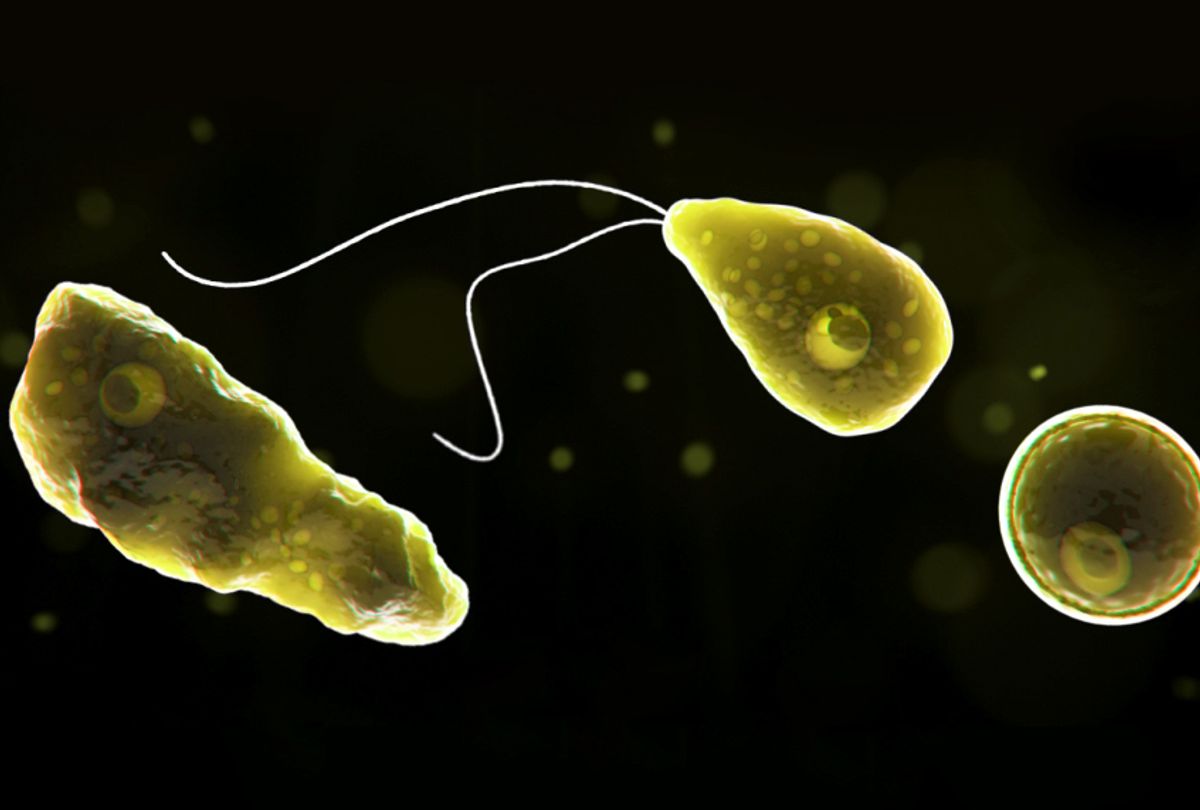

At first, doctors believed his symptoms — a fever and brain swelling — suggested he had bacterial meningitis. Doctors probed for other illnesses, and found that his cerebrospinal fluid tested positive for the brain-eating amoeba known as Naegleria fowleri. The official diagnosis: Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (PAM). This chronology comes via the late 29-year-old’s GoFundMe page; Stabile passed away on September 21.

PAM is a very rare and very fatal disease. Since 1962, 143 cases have been reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Only four of those cases survived. According to CDC data, Florida and Texas have had the highest number of PAM cases reported — likely because Naegleria fowleri is commonly found in warm freshwater like lakes, rivers, and hot springs.

“If water containing the amoeba goes up the nose, the amoeba can invade and cause a rare and devastating infection of the brain," Brittany Behm, MPH and Public Affairs Specialist at the CDC’s Division of Foodborne, Waterborne, and Environmental Diseases told Salon via email. “Each year, hundreds of millions of visits to swimming venues occur in the U.S. that result in zero to eight infections.”

Stabile’s case is the first to be reported in New Jersey, according to CDC data, but officials don’t think that is where he was exposed to the amoeba. A week before his symptoms led him to the hospital, Stabile was at the BSR Surf Resort in Waco, Texas. As Wired reported, CDC officials are testing the water to confirm if the water contains the amoeba. Behm said the CDC does not have testing results back yet, but that the epidemiology suggests he was likely exposed to it there.

In 2017, there were no reported cases of PAM. But in 2015 and 2016 there were 10 — which included one survivor, Sebastian DeLeon. Other survivors include one in 1978, and two in 2013. Behm said because the disease is so uncommon, it is hard to identify trends, but that reports do not appear to be increasing in recent years. CDC data corroborates this: in 1980, eight cases were reported.

There are preventive measures one can take to be protected from the disease — such as holding your nose or using nose clips when participating in water activities — but as the numbers show, human infection is rare. However, when a person is infected, timing is everything, and even that might not guarantee a life-saving end.

“[The] disease develops very quickly and for the successful outcome one must be treated when the first signs become apparent,” said Larissa M. Podust, PhD and Associate Professor at University of California San Diego who has researched treatment for brain-eating amoeba infections. “The symptoms are similar to bacterial meningitis, thus PAM may not be the first guess due to the rarity of this disease.”

This is what happened in Stabile’s case.

“Even if [the] disease is diagnosed, there is no medical treatment with the predicted outcome,” Podust told Salon. “There is a CDC-recommended cocktail of drugs, but a cure is not necessarily achieved even if the recommended treatment is performed.”

The recommended cocktail of drugs is known as miltesfosine, and is sold exclusively by the Orlando-based drug company Profounda Inc. That cocktail is what saved DeLeon in 2016. Profounda Inc. does not charge hospitals for the drug unless they use it, making it easier for hospitals to access it in the rare event they have to administer it. Todd MacLaughlan, the company’s CEO, tells Salon only 21 hospitals have it across the nation; a year ago, that number was zero. In DeLeon’s case, the drug had to be delivered. Lucky for him, it only took 12 minutes, as he was at the Florida Hospital for Children in Orlando.

MacLaughlan said he attributes resistance from hospitals as “apathy.”

“They’ve never seen it before, therefore they don’t need it,” he said.

Kali Hardig also survived the brain-eating infection in 2016 thanks to the medical cocktail. Dr. Matt Linam, who worked on the team that saved Hardig, said being at a facility that can manage brain swelling is key, too.

“This plays a major role in the morbidity and mortality,” he told Salon via email. “If you are not able to control the swelling, brain damage or death are likely to occur, even if you start the recommended medications.”

Linam added that prompt recognition of symptoms is important, too.

“The patient needs to present to a medically facility capable of recognizing and managing critically ill patients at the first onset of symptoms,” he said. “Delayed presentation or failure to recognize how sick the patient is becoming prevents any chance of survival.”

Not all who have received the drugs have survived, however. Zachary Reyna of Florida died in 2016 after coming in contact with the amoeba.

Dr. Podust said more funding is needed to develop and identify new drugs. In an email, she explained: “The major obstacle is the requirement of crossing the blood-brain barrier (BBB). The vast majority of small-molecule drugs are reluctant to cross the BBB. Our team in UCSD is well equipped and qualified to conduct the search for amoebicidal brain-penetrant molecules and to test them in animal model of infection. However, the animal experiments are costly. With the sparse funds we have, we can do only a few tests once in a while. At the same time, there is a demand to conduct more experiments to test different molecules and hypothesis originated in different labs. We would like to accommodate all the requests if NIH or philanthropic organizations could financially support our Center.”

Shares