If anything should be obvious in the wake of the 2016 election it’s that both major American political parties are in deep trouble, reflecting the larger trouble of a society potentially headed for state breakdown. The unacknowledged terrible record of the GOP’s “deep bench” paved the way for Donald Trump. On the Democratic side, Bernie Sanders’ promotion of popular progressive positions and his surprisingly strong 2016 showing challenged more than just Hillary Clinton, it challenged the entire direction of the party for over a generation.

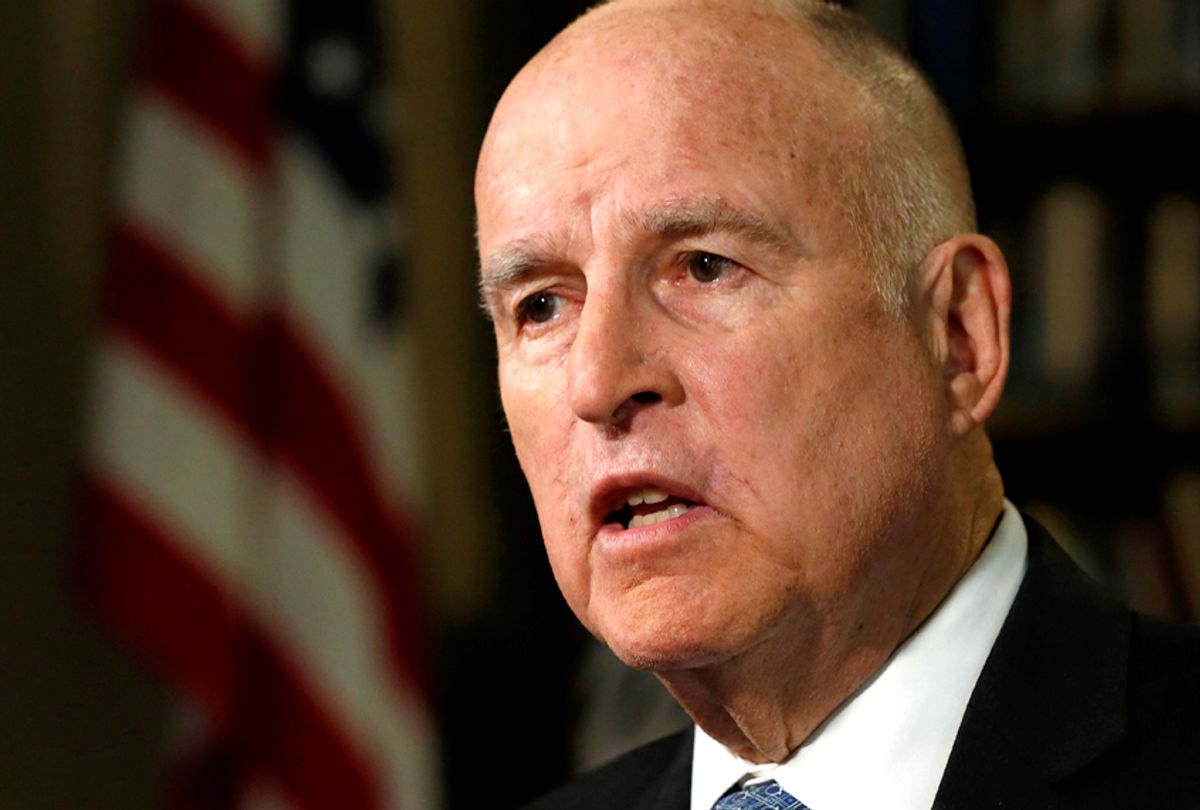

In the aftermath, both parties are struggling to redefine themselves, but in very different ways. The Republicans' redefinition is being driven by Trump, while Democrats are undergoing a more varied bottom-up process. One such perspective on what that involves can be gleaned by reflecting on the legacy of retiring California Gov. Jerry Brown — and what he’s left undone.

The view from the New York Times, "5 Takeaways From California Gov. Jerry Brown’s Last Bill Signing Session," was a bit of jumble, starting with Brown’s “lasting legacy as ‘the policy trendsetter of the country,’” and ending on the contrary note by mentioning his “a willingness to wield the veto pen,” usually against progressive measures, given Democratic dominance of the state legislature.

That contradiction — unrecognized and unreflected on by the Times — speaks volumes about Brown’s actual record and legacy, while the three other takeaways all reflect the impact of grassroots movements: Black Lives Matter for a “series of high-profile criminal justice measures,” and “[s]weeping changes to police transparency laws,” and the women-led Resistance and #MeToo movement for “[p]ushing back against gender discrimination and sexual harassment,” though vetoes and other caveats applied to those as well.

The good news for Democrats is how little Brown and his governor’s pen had to do with any of that progressive legislation, which actually spans a broad range of specific topics. His retirement won’t decapitate any of the driving forces involved. The bad news is how uneven the actual accomplishments are.

Vetoing safe injections

We could start with one of Brown’s headline grabbers, such as net neutrality, ending cash bail, promising a carbon-free future or placing women on corporate boards. But to really understand Brown’s mindset, and how it’s hobbled progress while seeming to advance it, the best place to start is with his veto of AB 186, which would have allowed San Francisco to establish safe injection sites, the first in the country.

Safe injection sites have a long history, dating back to the 1970s in Europe, but the first North American facility opened in Vancouver, Canada, in September 2003, as dramatized in the award-winning CBC show, “Da Vinci’s Inquest.” A study of its impact found that “Vancouver's safer injecting facility has been associated with an array of community and public health benefits without evidence of adverse impacts.” A more recent study in The Lancet found that overdose mortality rates decreased 35 percent within a 500-meter radius of the site in the first two years after opening compared to the two previous years.

Brown rejected all this evidence in his veto message, where he simply pretended that no such evidence existed — only beliefs on “both sides”:

The supporters of this bill believe these “injection centers” will have positive impacts, including the reduction of deaths, disease and infections from drug use. Other authorities — including law enforcement, drug court judges and some who provide rehabilitative treatment — strongly disagree that the “harm reduction” approach envisioned by AB 186 is beneficial.

Brown loves nothing more than framing things this way — fact-free, if need be — so that he can position himself in the Solomon-like center ... and then shift whichever way he likes. Thus positioned, he wrote that "the disadvantages of this bill far outweigh the possible benefits," that he did not believe it would reduce drug addiction, and that a punitive element had to be included in order to be effective: "Both incentives and sanctions are needed. One without the other is futile." He concluded by saying, "I repeat, enabling illegal and destructive drug use will never work. ... AB 186 is all carrot and no stick."

It was classic Jerry Brown: seeking to strike a “balance” between left and right, between compassion and punishment, casting progressives as naïve and simple-minded, and himself as sensible, pragmatic and wise. "There is no silver bullet, quick fix or piecemeal approach that will work. A comprehensive effort at the state and local level is required," he wrote.

But safe injection sites have always been advanced as an important part of more comprehensive efforts, and it’s willful ignorance to claim otherwise misunderstands this. Brown lectured public health experts with years of training and decades of experience as if they were children asking for candy. "California has never had enough drug treatment programs and does not have enough now,” he wrote. Gee, maybe he should complain to the governor about that!

If this account makes Brown seem preening, hypocritical and deliberately ill-informed, then it’s done its job. All too often, that’s who Jerry Brown has shown himself to be when the chips are down. He looks great in contrast to conservative bogeymen, dating back to his 1970s refusal to live in the lavish new governor’s mansion that Ronald Reagan built, and living in a rented apartment instead. He’s good at catching the winds of progressive change, as he did with his record of diversity in appointments during his first two-term stint as governor. But when the winds grow turbulent, there’s no telling which way he’ll turn.

This was further underscored by his uneven approach to bills at odds with federal law or policy. He signed some, even defiantly, while vetoing others, giving the conflict with federal law as part of his reasoning. Sometimes sound reasoning can support such differences (see net neutrality below, for example), but Brown’s signing statements give little, if any, hint of what that might be.

With that in mind, we can turn to his final signing record, and see it as symptomatic of how far progressives have moved the ball, where they’ve made it impossible to equivocate, and where there’s more work to be done.

Headline-grabbers

Above I mention four big issues in Brown’s final agenda: net neutrality, placing women on corporate boards, a carbon-free future and ending cash bail. The first three are relatively straightforward progressive wins, though not without complications. The fourth is far more ambiguous, with leading supporters turning against it during the amendment process.

Net neutrality (SB 822) was arguably Brown’s cleanest progressive bill-signing, even if Attorney General Jeff Sessions immediately filed suit to stop it. “Under the constitution, states do not regulate interstate commerce – the federal government does,” Sessions said in a statement. “Once again, the California legislature has enacted an extreme and illegal state law attempting to frustrate federal policy.”

The bill’s co-sponsor, State Sen. Scott Wiener, shot back: “We've been down this road before: when Trump and Sessions sued California and claimed we lacked the power to protect immigrants. California fought Trump and Sessions on their immigration lawsuit — California won — and California will fight this lawsuit as well.” Stanford University cyber-law expert Barbara van Schewick explained the basic legal argument:

An agency that has no power to regulate has no power to preempt the states, according to case law. When the FCC repealed the 2015 Open Internet Order, it said it had no power to regulate broadband internet access providers. That means the FCC cannot prevent the states from adopting net neutrality protections because the FCC’s repeal order removed its authority to adopt such protections.

Things were a little messier with SB 826, requiring publicly-held companies to include women on their boards of directors. It was a striking gender equity gesture on Brown’s part, but he vetoed bills impacting many more non-elite women: one that would have required public university student health centers to provide abortion medication, and make medication abortion services available, and another that would've required employers to provide a private space for employees to express breast milk. Still, it was another first-in-the-nation move, and Brown did advance a rationale for signing a bill that could well be struck down:

There have been numerous objections to this bill and serious legal concerns have been raised. I don't minimize the potential flaws that indeed may prove fatal to its ultimate implementation. Nevertheless, recent events in Washington, D.C. -- and beyond -- make it crystal clear that many are not getting the message.

As far back as 1886, and before women were even allowed to vote, corporations have been considered persons within the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment .... Given all the special privileges that corporations have enjoyed for so long, it's high time corporate boards include the people who constitute more than half the "persons" in America.

That’s Jerry Brown at his best. If only he hadn’t vetoed those other gender-equity bills almost in the same breath — a clear reminder that class and gender can never really be separated for progressives.

READ MORE: Feminists won't back down: What's next for #MeToo after the Kavanaugh vote?

On climate change, Brown signed SB 100, committing California to carbon-free energy by 2045, another major trend-setting move. But Brown’s cozy relationship with oil producers (Salon stories here and here), was not dispelled in his final days, as noted by RL Miller, chair of the California Democratic Party’s Environmental Caucus, and founder of the Climate Hawks Vote super-PAC.

“Brown's legacy on climate change will forever be defined by what he didn't do -- address oil production in California -- as much as what he did,” Miller told Salon. “He'll be remembered for [promising] 100 percent clean electricity by 2045, even though all he did was sign the bill -- it was Kevin de León's baby and Brown never lifted a finger before lifting the signing pen,” she said. (De León, the progressive state senator now running against Sen. Dianne Feinstein, also co-authored SB 822, the net neutrality bill.)

Although Brown will be remembered for enacting a “broad suite of energy efficiency regulations," Miller continued, "he has made it clear that he's happy to work with the oil extraction industry in California even as California produces the dirtiest, most carbon intensive oil on the planet. I'm hoping that the next governor [almost certainly current Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom] can confront the industry rather than cooperate with them.”

If the way forward on climate change is clear the same cannot be said about Brown's fourth headline-grabber, and end to cash bail in California. This was supposed to be a landmark achievement, in activists’ eyes. Other states have reduced cash bail, including New Jersey, New Mexico and Kentucky, but California will be the first state to eliminate it. But the bill that emerged (backed by the state court's Judicial Council) has gone so far off-track — adopting a computer risk-assessment tool that could defeat the whole purpose — that it drew the opposition of major initial supporters.

The new system will release people accused of most misdemeanors, while those accused of more serious crimes can be held until their arraignment or trial, based on the decisions of judges and prosecutors, relying on the mandated use of pretrial risk assessments. But such algorithms can encode hidden bias, just as judges and prosecutors can.

"The ACLU, NAACP and Human Rights Watch all abandoned their support for a move they initially hailed as a breakthrough for justice and fairness," Politico reported. "In these backers-turned-detractors’ eyes, eliminating bail was a means to an end: The real goal was fewer people in jail before trial. They now worry that California will head in the opposite direction."

http://twitter.com/johnlegend/status/1032756691069095936?

“We are concerned that the system that’s being put into place by this bill is too heavily weighted toward detention and does not have sufficient safeguards to ensure that racial justice is provided in the new system,” the ACLU’s Natasha Minsker told NPR.

"I was disappointed and I felt betrayed," San Francisco public defender Chesa Boudin told NPR, in another program. "The new SB 10 doesn't actually change the racist system of mass incarceration. It just expands it."

But some advocates still supported it, such as Joshua Norkin, who coordinates the New York Legal Aid Society’s decarceration project. “These types of reforms are generational,” Norkin told Politico, “and if you give up an opportunity for a substantial reduction in the jail population by passing a watered-down reform, then you may give up an opportunity to revisit that issue for another 20 years.”

This underscores is a persistent difficulty: organizing against an existing evil entails one logic, creating a positive good entails another. The two sometimes overlap, but often pull apart at crucial junctures. That’s what’s happened now with the signing of SB 10. It means that bail abolitionists will have to intensify their work on developing and articulating a much clearer, compelling and practical vision of what they are advocating for — work that Black Lives Matter activists in particular have advanced dramatically in recent years.

In that same spirit, several other criminal justice-related bills are worth noting, most notably, two significant police accountability bills Brown signed: AB 748, requiring the release of body camera footage within 45 days of a police shooting or any use of force that causes death or great bodily harm, and SB 1421, allowing public access to police records in use-of-force cases, as well as sustained investigations into on-the-job dishonesty or sexual assault. The later reverses a law signed by Brown during his first two-term stint as governor.

Brown also signed two significant juvenile justice bills: SB 1391, which prohibits 14- and 15-year-old criminal defendants from being tried as adults, and SB 439, which ends the prosecution of children under age 12, except for murder and forcible sexual assault. In a similar spirit, Brown signed SB 1437, providing that an accomplice to murder will no longer necessarily be subject to the same sentence as the actual killer.

A mixed bag: #GunSense, #MeToo and immigration

Two other areas saw a lot a progress, marred by some striking vetoes. Gun safety was strengthened by a number straightforward measures: Raising the minimum age to purchase any firearm to 21; imposing lifetime gun ownership bans on "dangerous gun owners" and those convicted of domestic violence; requiring applicants for concealed-carry weapons permits to undergo training and testing; a ban on "bump stocks"; and making clear that ammunition can be confiscated as part of a gun-violence restraining order.

But Brown also made several frustrating vetoes, on bills allowing co-workers, employers or teachers to request gun violence restraining orders; banning gun shows in San Francisco; and limiting purchases of rifles and shotguns to one per month.

READ MORE: Beto O'Rourke & Martin O'Malley: the dark horse ticket that could beat Trump in 2020

Brown also signed two significant bills aligned with the #MeToo movement, while vetoing two others. He signed SB 820, banning nondisclosure agreements in sexual harassment, assault and discrimination cases, and SB 1300, prohibiting employers from forcing new employees or those seeking raises to sign non-disparagement agreements or waive their right to file legal claims.

And then there were his two vetoes: AB 1870, which would have extended the deadline to file a harassment or discrimination complaint from one year to three, and AB 3080, which would have banned employers requiring private arbitration rather than going to court. In his veto message, Brown wrote that the bill “plainly violates federal law,” which did not stop him on other bills he signed, as noted above

That bill was the only measure that reached the Brown's desk this year to be labeled a “job killer” by the California Chamber of Commerce. That label is a device used to push the notion that the real purpose of business is to “give” people jobs — the private jets and mansions accumulated by CEOs are just a minor side effect. But for all its absurdity, the Chamber remains a powerful adversary for progressives in the state.

Altogether, the Chamber has identified 218 "job-killer" bills during Brown's current two-term stint. Only 12 percent have reached his desk, with 15 being signed and 11 vetoed. That's an even better record, from the Chamber's point of view, than under previous governors: About 27 percent of them reached Arnold Schwarzenegger's desk (and he vetoed nearly all of those), while almost 36 percent reached Democratic Gov. Gray Davis' desk, and he signed most that did. By its own rough accounting, the business lobby has grown significantly more successful over time, even as GOP power in the state has shrunk.

Finally, Brown quietly vetoed two bills aligned with California’s “Sanctuary State” stance in opposition to the Trump administration: SB 349, which would have prohibited immigration authorities from making arrests inside courthouses and SB 174, which would have allowed non-citizens, legal residents or otherwise, to serve on state and local boards and commissions that now require citizenship. (In the 19th century, European-born non-citizens were encouraged to similar civic participation. But that was a different time, and they were "white.")

Off the radar screen

Nowhere on the national radar screen is one very important California bill dealing with wage theft. Wage theft is a massive criminal problem concentrated on lower-income workers. A 2017 report from the Economic Policy Institute estimated annual losses of $15 billion, slightly more than the $14.3 billion in property theft losses estimated by the FBI in 2015. In California, port truckers are especially hard hit, due to their misclassification as “independent owner operators” and getting saddled with the multi-billion dollar costs of new, cleaner-burning trucks since 2008.

A 2014 report from the National Employment Law Project, "The Big Rig Overhaul" estimated wage and hour law violations in the range of $787 million to $998 million each year. Stepped-up state labor law enforcement has since resulted in more than $45 million in judgments due to 400 drivers, but with inadequate enforcement, largely due to Trump-style shell company shenanigans, the practice has continued unabated.

SB 1402, which Brown signed on Sept. 22, could change that dramatically by making retailers jointly liable for wage theft by the transportation companies they employ. “Retailers using their power to end exploitation and restore good jobs for workers at our ports will mean port truckers are left behind no more,” said the bill’s author, state Sen. Ricardo Lara. It could make an enormous difference for the 16,000 misclassified port drivers in California, and similar laws could benefit almost 50,000 port truckers nationwide, if other states follow suit. But the joint liability model could help combat wage theft more broadly, perhaps helping millions. It’s an innovative new approach whose significance has yet to be realized, but it’s come about only after more than a decade of trucker organizing, with 16 strikes in the last five years.

What’s missing?

What’s not included in Jerry Brown's legacy are three big things: missing from all of the above are three things: Reducing income inequality (California’s poverty rate still leads the nation), strengthening democracy and advancing progressive causes more generally. All three are broadly interconnected, since California’s electorate — like America’s as a whole — is considerably less progressive and less concerned about income inequality than the general population as a whole, a fact that I’ve written about before.

Any measures that would substantially increase voting and political participation would, almost by default, greatly increase support for progressive policies, and make it easier to turn them into reality.

The 1999 book, “Reading Mixed Signals” by Albert H. Cantril and Susan David Cantril found that the pool of likely voters was almost evenly divided between supporters and critics of government, while those unlikely to vote were far more supportive of government programs, 55 percent to 32 percent. This divide is even sharper looking only at steady supporters and critics—those whose ideological views align most consistently with support or opposition to specific spending programs. Steady critics are 24 percent of likely voters, but only 12 percent of unlikely and non-voters, while steady supporters increase from 36 percent of likely voters to 42 percent of unlikely and non-voters. In short, those who don't like government are far more likely to vote than those who do.

As I noted here in July 2017, the same general findings apply to California specifically:

In 2006, the Public Policy Institute of California produced a report, “California's Exclusive Electorate,” which I wrote about at the time. It found that “the difference between voters and nonvoters is especially stark in attitudes toward government’s role; elected officials; and many social issues, policies, and programs.” Nonvoters, for instance, were found to prefer higher taxes and more services to lower taxes and fewer services by an enormous margin, 66 to 26 percent. Among actual voters, the split was nearly even: 49 to 44 percent.

I went on to note that a more recent PPIC update report had similar findings. While California is currently awash in activism focused on midterm turnout in key House districts, what’s missing is a coherent long-term plan to increase the participation of currently disengaged voters. There’s nothing in the legislative process to address this, so no bills showed up for Brown to sign or veto. But it’s the single most important thing for progressives in California to addreww if they really want the state to live up to its reputation as a harbinger of change.

Four things could be done that I’ve written about here before:

- Adopt proportional representation, which gives coherent minority views a voice in legislative deliberations.

- Adopt ranked-choice voting, which lets people vote for candidate in the order they prefer, without fear that they’re helping a candidate they detest. This ensures that whoever wins is actually supported by a majority of those who vote andencourages more collegial and informative campaigning.

- Adopt multi-member districts, which lets a combination of the first two reforms deliver better representation of voters' views without sacrificing geographically grounded concerns.

- Reform the initiative process, so it’s reserved for major constitutional matters, and so that initiatives can withdrawn by voters, after legislatures respond.

These suggestions aren’t meant to be comprehensive, just a reminder that there are many constructive alternatives that progressive activists have invented, developed and refined over the years. Jerry Brown will be remembered for advancing progressive reforms in some areas while blocking or constraining others. If he's not the Resistance hero depicted by the national media, he's also not the main character in California's story. Those who bring different perspectives together, reject the logic of limited options and push for change from the bottom up are building the future.

Shares