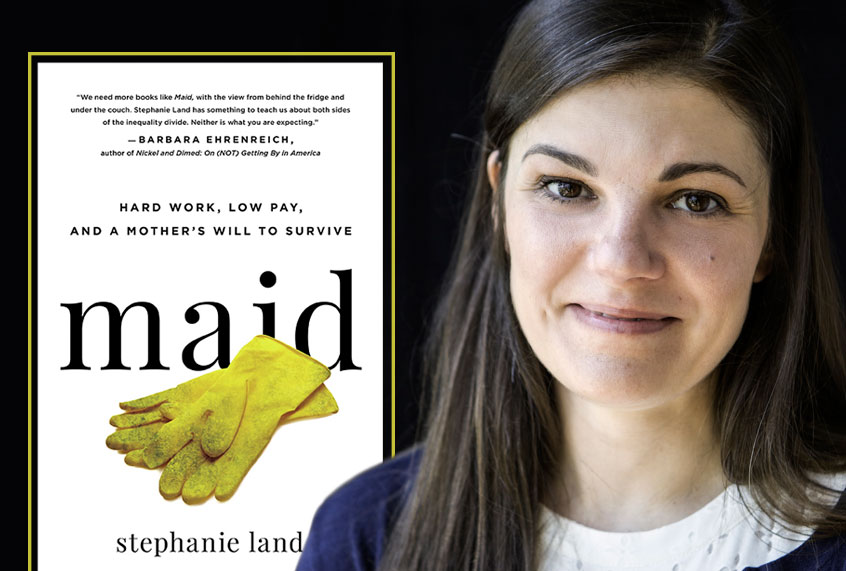

“I’m sorry I’m so distracted,” Stephanie Land says to me. Not that I could tell. At that point we had been on the phone for 45 minutes talking about her new memoir “Maid,” which chronicles the years she spent working as a housecleaner, balancing hard physical labor in a low-wage, high-stress job with single parenting and college, and throughout our conversation Land’s focus has not ever appeared to waver.

“I’m actually cleaning my house while I’m talking to you,” she says with a laugh. “I guess it’s ironic.”

Unbeknownst to me — though I’m not surprised, given the amount of advance buzz behind this book — a crew from a network TV show is on its way to her home to shoot a feature later that afternoon. Land’s smoothness in carrying on a conversation about the policy and cultural blindspots that keep the country from being able to make meaningful progress for the working poor while basically doing two jobs at once is a living example of the determination and grace on display in her memoir, in which she renders vividly the back-breaking and often surreal work of deep-cleaning strangers’ homes while navigating the baffling bureaucracies of government assistance programs ostensibly designed to help her, all the while daring to dream of — and then build — a better future for herself and her daughter.

Land’s personal story brings together so many intersecting issues which are rarely considered from a holistic perspective, such as the dangers facing women in abusive relationships who don’t have financial safety nets; the health issues that manual labor and substandard housing can cause or exacerbate for the entire family, and their financial implications; the affects of hunger and poor nutrition on a working parent; the psychological and financial tolls of unstable hourly-wage work; and the public assistance systems that are frequently more frustrating than helpful. Land and I spoke about all of that and more. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

In your experience, what is the biggest misconception out there about women, work and economic insecurity?

I feel like we don’t always take into consideration that a lot of the times women are the ones who are the primary caregivers of children, and so they hold that responsibility of making sure their kids are taken care of while they’re at work. That was a huge drawback for me, because I had to find a job that was within daycare hours, especially on government assistance and accepting a child care grant.

Only certain daycares will take the grant from the state, and there’s all of these rules and regulations around that, and you have to have a job before you can get the grant, and so there’s kind of that juggling that feels a little impossible. Because the job wants you to start immediately, and then you’re like, “Oh wait, I have to go apply for childcare.” Which can take a few days or up to a week to get approved for.

You have to work a standard nine-to-five job. Because that’s when daycares are open for the most part, and they’re the prime hours for most people or most employers, or most positions, definitely the entry level work that I was trying to find. That was why I ended up being a house cleaner and working for such low wages — that was the only job I could find that fit into all of those parameters. Because at the time it was at the height of the recession and I couldn’t find a job at all.

It’s very illuminating, the fact that those, like basically how out of touch the requirements for things like daycare resources are for the realities of working women, especially single mothers. How do you go pick up a waitressing job when you know your prime hours for that are going to be evening and weekend hours? That’s maddening.

Yeah. Also my [work] experience was mostly working at coffee shops. I was in my late 20s and I was just kind of bumming around until I decided take college seriously and become a writer, whatever I was dreaming about at the time. Then to suddenly not be able to get a job that I had 10 years of experience for, because I couldn’t do those evening and weekend hours — when you’re starting off, you get all the bad shifts, and you fill in for people and you have to be on call. Employers don’t want to hire single moms with kids, because if the kid’s sick then they can’t work, and it goes on and on and on. It’s really incredibly difficult to find a job in that situation.

With all of the discourse out there around feminism and the workplace, it doesn’t strike me, at least, as being as inclusive as it could be of women who do shift work, or those who do work like housecleaning, who are employed in areas that are outside of the corporate or creative fields that get most of the oxygen in the conversation. What do you think we can do about that?

I’m a huge believer in universal childcare. Not only should childcare be more affordable, or just covered [outright], we should be paying people who take care of our kids a living wage too. I mean most daycare workers can’t afford to take their kids to the daycare center that they work at.

I feel like there’s a lot of stigma surrounding the work requirements for food stamps and things like that. But I feel something that maybe people can get behind is childcare, and health insurance for kids. If we can at least make sure that our children are taken care of, that will ease the minds of their parents who are trying to work.

That was the one thing that really kept me from working the amount of hours. It’s still is. I really think if we can get behind some kind of — I want to say free child care, but I don’t know if that would be even possible. That feels like a huge dream.

Universal affordable child care seems like a thing that can unite women in the workplace across class lines. Because it’s really only the top percent of earners who don’t have to worry about that, right? I feel like all my friends who have jobs and kids are stressed out about their daycare costs.

Yeah. Right now, I’m paying $650 a month for full time daycare, which is a huge expense. That’s my biggest bill, besides housing. But three years ago, when my [younger] daughter was about a year old, I was applying for childcare grants and the packet was like a quarter-inch thick. It was enormously stressful, and I was self-employed and freelancing, so I didn’t have a regular paycheck. I had to gather proof of income for the last 3-4 months, and when you’re a freelancer that’s a lot. I did that, and I had to hand in the parenting plan and child support for my older daughter, who I wasn’t even applying for childcare [coverage] for. After all of this, they told me that I made $100 too much to qualify for this child care grant.

I was on the phone with the lady and I was like, “Are you kidding me?” She said, “Well it looks like you work mostly after your kids go to bed.”

Because that’s the only time that I could, after they were out for the night. I would stay up till two or three in the morning working. She’s like, “It doesn’t even seem like you need daycare during the day.”

That makes me think about one theme that I saw running through your book. An example that stood out, because it was an ongoing issue, was when you moved into the studio apartment that had mold issues, which meant your daughter was often sick. As you referred to earlier, that means that you’d lose more hours at work, because you’re the one as a single parent who has to stay home with her or take her to the doctor. There’s no guaranteed paid sick time for so many workers in this country.

I’m wondering if you could talk about any experiences that you had that deal with how expensive it can be to be poor in America?

One of the main things is that you can’t buy food in bulk. Not only because you can’t afford to buy a bunch all at once — you can’t afford to spend 20 bucks [at a time] on a flat of beans, or whatever is healthful for people to eat. It’s not only that. In order to do that, you need a car that can bring it home. You need storage space in the house, cupboards. I didn’t have any food storage where I lived, it was very minimal. Then just having the basic funds to be able to afford to do those really big grocery shopping trips. I would buy the four packs of toilet paper [instead of in bulk], which are way more expensive. There was no way I could have afforded a Costco membership or something like that.

There’s no way to save up money, and there’s no way to budget and plan for the future either, because everything is so day-to-day and you’re just scrambling. Even $10 short can mean that you don’t pay the electric bill and then that puts you in the red. Then you have a late fee and then you have, if you bounce a check, all of a sudden you have the bank fees that are just snowballing on you. Then you’re $100 in the red, and there’s no way that you can come up with that money to get your account in good standing again.

I went to the grocery store this morning and I bought a drink and breakfast items, and didn’t even look at the register. I’m to the point now where I’m financially secure enough that I’m not stressing over every single penny that is rung up whenever I go to the grocery store. It was probably $10. That kind of thing, before when I was really struggling, it was unheard of.

I only had $50 a month in spending money and all of my toiletries had to come out of that. Like soap, shampoo, sponges, paper towels, tampons, and all of that. That’s your $50 right there and so there is just no money. It’s hard for even me to remember that it was like that. I’ll download a song on iTunes now without thinking about it, whereas before there’s no way that I would do that — $1.29, that’s a lot of money.

When you’re not able to go hit the huge sales, or really take your time combing through everything at Goodwill — there’s so many things that people do to live a frugal life, but they’re spending their time to do it. I didn’t have that luxury either. I had to do my grocery shopping in a half an hour.

I had to know the store by the back of my hand, because I had exactly $187 a month to pay for food. I knew exactly what I needed to buy and how much it would cost. There’s just this constant register in your head of like, OK, so I paid this bill, so this should come out on this day. That means that I have like $5 extra to spend this grocery shopping trip. What am I going to get? We need toothpaste. It’s that tight of budgeting.

When you have a car that keeps breaking down because you can’t afford to make a car payment, or you can’t afford to pay the full amount of insurance, the full coverage or whatever, so you can have a loan. So you have this car that keeps breaking down, because you can only afford the $100 or whatever it takes to fix it instead of buying a car that doesn’t break down.

Then like you pointed out earlier, if you pick up more shifts, more hours, to make more money, then you’re in danger of making “too much” and losing your childcare grant. But then the extra hours still don’t cover the cost of childcare. It seems like the math is so constantly maddening.

The system does not encourage you to improve yourself. The system, I think, it’s set up for a full-time minimum wage worker. It’s set up to supplement the wages that we’re not paying people, because they can’t live off of it. A fifty-cent raise could mean you lose your food stamps and that could be anywhere from $200 to $400 a month depending on the size of your family. So it’s really not worth it to go for those promotions, or to get an education, or anything like that because you’re penalized for it.

Let’s change course a little bit and talk about the houses. I have to say personally, I loved you for being open about snooping in your client’s house: This is a woman after my own heart. I would not be able to resist myself either. What did you learn that surprised you about people in general, and how they left their homes to be looked after by a stranger?

There were a lot of things that people left out, or in the trash, or the condition of their toilets, or just random items on the counter. And there was this one time that there was always these huge loogies in the shower. I got there and it’s like, “Really?”

For me I would be embarrassed. So I always told myself, “Oh, maybe they didn’t realize I was coming today.” Like the bottle of lube that was always on the nightstand. Why would you leave that sitting out knowing that this stranger was going to come into your home and have to dust underneath that?

I’ll say this as someone who’s never had a house cleaner, but has also never cleaned a stranger’s home: Do people just get to this state where they either don’t have embarrassment about it, or self-consciousness, or that they just don’t think that a writer is cleaning their house and might tell the world about it?

Well, I don’t think any of them thought that. Maybe they’d had a house cleaner for so long, they didn’t think about it anymore, or it didn’t cross their minds. I really don’t know. If it were me, I would have put stuff away. I mean not only because of I didn’t want to leave out all of my embarrassing things, but also it helps the house cleaner to move a lot faster if there’s no clutter. To me it’d be like a time saving issue.

One thing that I just didn’t know before I became a professional writer is how so many careers — not just writing, but other creative careers too — become more attainable because of things like family money or spousal income. People don’t really like to talk about that. That definitely makes class an issue in the artistic and publishing worlds, despite whatever romantic notions that I or any of us might have heard about them when we were younger.

Has there been a moment in your writing career, either related to the book or not, where those background differences or class differences became suddenly visible rather than hidden?

Well, there were a lot of missed opportunities. I couldn’t go to writing residencies, or [the major annual writers conference] AWP, or even readings for local visiting writers and authors. There were a lot of times that I couldn’t go to those because I couldn’t afford to hire a babysitter, so I had to get over a fear of missing out with all of that.

I think especially in academia, we are coached to go the route of paying to submit our writing to small publications, like the presses and the quarterly reviews and all of these that are considered “prestigious.” As a writer in a college program, that’s the route that you’re taught to go. Not only are you not getting paid to publish something, you are paying them to read it, and then you go for the small press type of publisher for your book that’s it’s more of a literary thing . . . everybody wants to be the next Raymond Carver or something.

For me, I couldn’t do that. There was no way. I had to support my family and so I immediately went for the publications that could pay me for my writing. I had to be paid for my time. I had to support my family. It was always about the money. I kind of felt like, I don’t know, it felt like I wasn’t a real writer or like my writing was cheapened by that time.

I felt like I was selling out a little bit. It really wasn’t until people started responding to the book like they have been that I have actually felt like I was a good writer.

Up until this point, it’s been like, “I’m just a writer who gets paid,” or “I’m just a freelancer.” I wasn’t a “real” writer, in some way, in my head. It’s a bummer that the writers who scramble are not as respected, I feel. I might just be talking off the chip on my shoulder.

I think your experience is one that is shared by a lot of writers. People feel like that’s their only chance to get their work in front of a prestigious editor, which then is the thing that gets them the grants and the fellowships, which also then help get them the book, which gets them the teaching job. You have to float yourself for so long and people who have a financial cushion have a leg up.

Yeah, I mean there’s that part of it too. When I applied for the MFA program at U of M, I could only apply to that one program. I couldn’t apply to ten and be like, “Oh yeah, if they accept me, sure, I’ll move to Iowa.”

I also think MFA programs want to make sure that their writer is financially supported, because if they’re not, they don’t really see that they have a feature in writing. I think there’s that aspect of it too. It seems like an out-of-the-ordinary thing, that an MFA program would take on someone who has to work three jobs to make it through, and someone who has to struggle. Because they don’t really see the opportunity of their writing career taking off after they’re done with the program.

Speaking of academia, a related conversation that I’ve observed over the last decade or so as the student loan crisis has worsened and as the gig economy has encroached on industries that were formerly more stable: there’s been a narrative push about why not everyone needs to go to college. A lot of people almost get romantic about the idea, of encouraging kids to go into the trades, or manual labor, instead. But it strikes me that the people pushing this idea, by virtue of their platforms, are rarely those who have actually done that kind of work themselves. Based on your lived experience, is “you don’t have to go to college” sound advice for, say, a young woman who’s about to graduate from high school?

I don’t know. I have a lot of mixed emotions about that. My parents told me when I was 17 that they couldn’t afford to pay for my college education. At the time that was very surprising, and so I decided to make sure I knew what I wanted to get out of college before I even began. So I took a class here and there, like I would take a creative writing class or whatever, occasionally throughout my 20s.

Because I didn’t really know you could go to college to be a writer. I didn’t know that was a thing until much later. I just didn’t go, because to me it was a huge investment without really knowing what the payoff would be. When I finally did go, especially when I decided to get a degree in English — get an art degree as a single mom, that I was growing rapidly into debt for — I graduated college feeling like I had failed my family.

Graduating college was not fun for me. Because it just meant I am now $50,000 in debt, and the payment for the $50,000 is going to be $500 a month. There’s no way that I’m ever going to be able to afford that on top of rent and on top of all of these things. I felt a huge amount of guilt for that. I think that was why I worked so hard to make it as a freelancer, trying to make up for this huge, to me, selfish decision that I had made. That’s my own personal experience and it’s hard to not have that bias.

I can tell you with my daughter Mia, she’s 11 and a half, she wants to be an astronaut. I’m encouraging her now, like, “Get good grades, so you can get a scholarship.” I’ve always told her that I would pay for her first year of college as long as she went somewhere else. Because I think right out of high school, it’s more about the experience of being away from home, and being out on your own. I think there’s a lot of value in — it sounds hokey, but going out and finding yourself a little bit and having some experiences that are your own before really deciding what you want to do and what you want out of college. It is a huge expense for someone like me whose parents couldn’t pay for it, so there is that added weight.

I think a college education is very valuable and I think that more people should have access to that. I think it’s kind of turning into this elite thing, because it is so expensive. Because of that it’s a bigger decision of whether or not to go.

It seems like the common theme is why can’t we as a culture get it together enough to set everybody up for success, however that looks like for them? There are so many gaps for people to fall through.

Yeah, especially if you’re on food stamps. You are required to work 20 hours a week. If you’re going to school full time. If you’re on TANF, which is the cash assistance, whatever they call welfare, you have work requirements when you’re on that, also 20 hours a week. College does not always count towards that. You have to be in a certified, pre-approved program that’s usually a trade and your instructor has to sign off that you were actually in class and sign off on how many homework hours. It’s a huge hassle and a huge amount of paperwork, and not that much benefit. Cash assistance is not that much money. It’s a couple of hundred bucks a month maybe.

But for me, my final year of college, Mia was six, so I had to work 20 hours a week, and since I was a full time college student that wasn’t really possible. I’m in class all the time and I couldn’t work that much because otherwise I would never see her.

I got kicked off food stamps for a period of time because of that. I think they only covered her, and I had like $100 a month in food stamps. It’s a really difficult situation that people in those circumstances are in, especially. That’s kind of why I feel like college is such an elite thing now, because the more people who are struggling to get by and relying on those government assistance programs, the less access they have to a higher education.