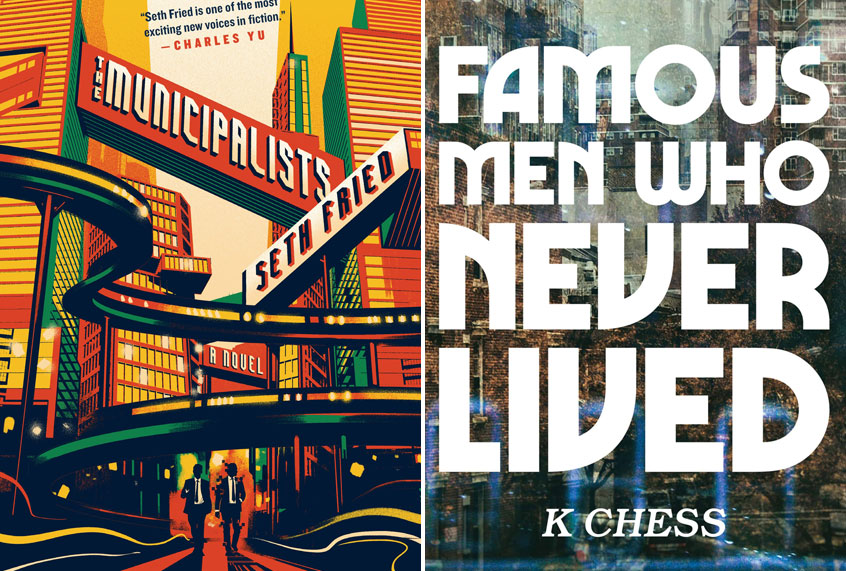

Seth Fried: This spring will see the release of what I feel are two very exciting debut novels. The first is “Famous Men Who Never Lived” by K Chess, a book about immigrants from a parallel world. Chess’s novel is as timely and powerfully written as it is jaw-droppingly imaginative. The second is my own debut, “The Municipalists,” which friends have advised me to stop pitching to everyone as “The Death and Life of Great American Cities” meets “Jeeves and Wooster.” Both my and Chess’s novels are speculative, deal with alternate versions of the U.S., and feature characters striving to find their place in worlds that have been fractured.

One of the most nerve-wracking things that can happen to you as an author is to share a release year with a book that’s a little too good for comfort. But I’ve managed to set aside my professional jealousy long enough to talk with Chess about her book and my own. Below we discuss alternate worlds, writing action sequences, world-building, and the political dimensions of our fiction.

Fried: In your novel, you’ve created a complex and vivid world that only exists in your characters’ past. The effect is remarkable in that we’re introduced to all the strange and cool differences of your invented world while we’re simultaneously longing for it as something irretrievably gone. How did you go about that? Did you do your world building in a straightforward way and then have your characters flavor it with their nostalgia after the fact or did you build the world with those feelings already in place?

“Famous Men Who Never Lived” alludes to another version of New York City, but “The Municipalists” actually takes place in one. For me, so much of the pleasure of the book derived from the extremely specific and convincing details of Metropolis’s invented geography and systems. You live in New York yourself, right? How much comparison are you inviting? I also feel like it’s important to note that we’re seeing the city through the eyes of Henry, who doesn’t live there, but who is a huge fan of the place. How did you decide he was the right person to introduce and mediate your world?

But about your book, one of the bittersweet things when you’re creating a fictional world is that the joy of creation can drive you to generate a lot more details than the story requires. One of the many impressive things about your novel is that the details you include manage to evoke a whole world but never stray far from your characters’ most urgent memories. Was this hard to do? And were there any tough cuts for you? Any aspects of your invented world that were awesome but also ended up distracting from the thrust of the story?

Chess: I love this question! I came up with alternate-universe versions of two Brooklyn neighborhoods, complete with fictionalized history to explain the physical features I imagined. I had this alt-Park Slope that was isolated from the rest of the city by highway and run by organized crime, which is where Hel had an apartment with her husband and son in the other world. And I had this alt-East New York, built around radical communitarian neighborhood services, working class in the ‘50s and moving up to upper middle class by the ‘00s, where the writer Ezra Sleight did his work. In order to write with authority, sometimes you have to know more than what you put in the book.

Speaking of utopias! At first, your book seems like a portrayal of a very cool one, but by the ending pages, it’s developed into a sneaky but trenchant critique of urban planning and an exploration of terrorism. These are real and timely issues for cities, obviously. Do you see your book as political? Which came first for you, the plot’s climax or the thematic one?

Fried: Some of this just grew out of a nuts and bolts sense of craft, since, as a writer, you’re always pressing on your character and trying to complicate his or her worldview. Henry loves cities and is a true believer. He sees them as an antidote to the grief that defined his childhood. So a lot of that initial impulse was just me getting in my main character’s face and trying to force him to develop a more authentic relationship to the world around him. But a lot of it also mirrored my own realizations as my research deepened my understanding of a lot of the systemic problems in cities. I had to let my (and Henry’s) optimism be tempered by the realities of the situation. From there I tried to have the story reflect the challenges of facing unpleasant truths, which is something that seems to have become more explicitly political in recent years. But mostly I wanted it to be a contemplation of how the individual fits into the political. What is our relationship is to our own ideas? What should we let them turn is into? Or, conversely, how do we let our ideas grow or change without abandoning our core principles?

I would also love to hear about the political dimension of your book, which explores a subject we’ve all been thinking about in a heightened way over the past few years: immigration and society’s treatment of the “other.” You’ve created a situation in which privileged segments of a world like ours suddenly experience what it’s like to be seen as unwelcome guests. It feels like a really necessary and relevant exercise in empathy. What drew you to this idea? Is your relationship to it explicitly political or am I maybe projecting stuff onto it?

Chess: No, not at all. In “Famous Men Who Never Lived,” I wanted to write about loss and about feeling like a stranger, experiences that are universal and apolitical. I also wanted to write about what it’s like to be part of an unfairly maligned minority group. In the U.S. today, anti-immigrant sentiment often takes the forms of racism and contempt for the countries from which people are migrating. This is in the news a lot, obviously, though it’s nothing new. But what if some of the distance between asylum-seekers and hosts were removed? What if the newcomers just seemed like regular old New Yorkers?

This kind of what-if is an amazing thing that science fiction can do, and I wanted to explore it through individuals. Tayari Jones says that “a story has to grow from its characters,” and quotes her mentor, Ron Carlson’s advice: “Write about people and their problems, not problems and their people.” The characters from the other world struggle with assimilation. As real immigrants do, they’re under pressure to give up past attachments. And, like real immigrants, they’re seen as an economic threat, disliked and distrusted. For Hel, a privileged woman from the dominant culture, facing this impersonal resentment is an extra challenge. It’s new and extremely surprising to her. Her partner Vikram, who has been marginalized before, is not surprised. That contrast is intentional — and political.

Fried: We’re both coming at speculative lit from a literary background (is that fair to say?), but both our books have action sequences(!). This made me incredibly nervous when I was drafting “The Municipalists,” so I wanted to ask how this was for you. I particularly loved and was jealous of your main character learning how to tail someone, which felt so cool and exciting. There were several other action-y moments that were gripping but which I refuse to spoil here for the reader. Was this new for you? Do you have any craft tips for writers who are nervous approaching capital-A action for the first time in their projects?

Chess: Writing physical action can feel really effortful, like you’re posing dolls and making them hit each other! I used to believe it was essential for me to know exactly who was where and what was going on at every single moment. I’d take an enormously descriptive draft and try to cut it down. As I get more practice, knowing everything no longer seems as helpful. It’s far from the experience of participating in action, right? I agree with you that decreasing the level of specificity is important for pacing. I try to do this selectively. To me, action is fundamentally grounded in POV. When writing limited third [person], I ask: What kind of thing would this character notice in a state of heightened tension? Finding just a few details that are indisputably right can help the reader picture the rest of the scene. And an equally important question: to what would this character be oblivious in this moment? That helps me know what I can get away with leaving out. It’s important to keep in mind that action scenes on the page are stylized and distorted, artificial representations of a real experience. Probably the best way to learn to write that way is to practice writing that way.

You come from a humor-writing background, too (is THAT fair to say?) while I’m just one of those people who wishes I could make my friends laugh. It seems to me that the heart of your book is how Henry, the human bureaucrat, and OWEN, the off-the-wall AI, learn to be partners. We experience the friction between them through humor. Can you tell me the secret to being funny? Also, OWEN’s projection isn’t constrained by the laws of physics; a lot of the humor is visual or slapstick in nature. Have you tried this on the page before? What was it like to write?

Fried: I think one of the biggest tricks is just to create an expectation and then violate it. OWEN’s antics are funny (hopefully) because we’re seeing them through the filter of Henry’s stick-in-the-mud expectations. For example, let’s say you’re writing a scene where your character tells her best friend about her theory that Jon Hamm is secretly a lizard person. That scene might reveal your character’s personality, but it wouldn’t really be that funny because people are expected to say pretty much whatever they want to their close friends. Now if you were to write a scene in which your character explains that same theory during a job interview, suddenly it’s much funnier because the situation of a job interview has a system of expectations that provides tension you can exploit. There are lots of fun mechanical things like that you can pick up pretty easily. The rest is all stuff that in my humble opinion you’ve already mastered as a fiction writer.

And the visual aspects of OWEN were really fun to explore. My short stories have always been kind of manic, but this was the first time I decided to have a character go full Bugs Bunny. I had a lot of fun with it, but there were challenges in that some visual humor just doesn’t work on the page. Often there would be something that made me laugh when I imagined it, but that mental image just wasn’t effective in prose. In film or animation, something unexpectedly entering or leaving the frame is hilarious, but in fiction it’s harder to make that work because our frame is imaginary and amorphous. Though the constraints in a project always end up being the best part. If it had been easier to earn OWEN’s visual gags, that’s probably all I would have done with him. Instead I realized that his dynamic with Henry was where a lot of the humor was, which caused me to spend a lot of the early drafts developing the relationship that I think of as the heart of this book.

It’s amazing how many big, project-altering decisions can just stem from simple realizations about craft. For me, writing a novel felt like I was a million dogs trying to stand up in a million cars. Before I let you go, what do you have in the way of advice for writers who are approaching a novel for the first time?

Chess: What do I have in the way of advice? Write about something in which you’re passionately invested. My book and Seth’s are both about worlds that don’t exist — but so is every book, really, whether it takes place in a middle school or on a pirate ship or at a book club or in a prison. We make them up, and that’s powerful. Don’t let anyone discourage you, at least not in the beginning stages, when your paracosm is fragile. If you follow a set of characters through circumstances that you find truly interesting, if you seek to answer questions that provoke you, your book will feel alive. I don’t think you can go wrong if you’re writing to entertain yourself.