In 2013, Lara Prior-Palmer became the youngest rider and the first woman to win the Mongol Derby, a grueling endurance race across 1,000 kilometers of the Mongolia Steppe. The 10-day cross-country race retrace’s Genghis Khan’s horse messenger system route from the 13th century. Londoner Prior-Palmer, 19 at the time and a year out of high school with “dead end jobs” and equestrian competitions occupying her time as she waited to hear about applications to work in an orphanage in Ethiopia or an organic farm in Wales, embarked on this adventure not after training for years with dedication and purpose but after coming across the race’s website — entry deadline already blown, the fee more than she could afford — and entering, by her own admission, on a whim.

It was going to be either too much, as Prior-Palmer puts it, or nothing at all. Her aunt, the World Champion equestrian Lucinda Greene, tells her matter-of-factly, “I suspect you won’t make it past day three, but don’t be disappointed.”

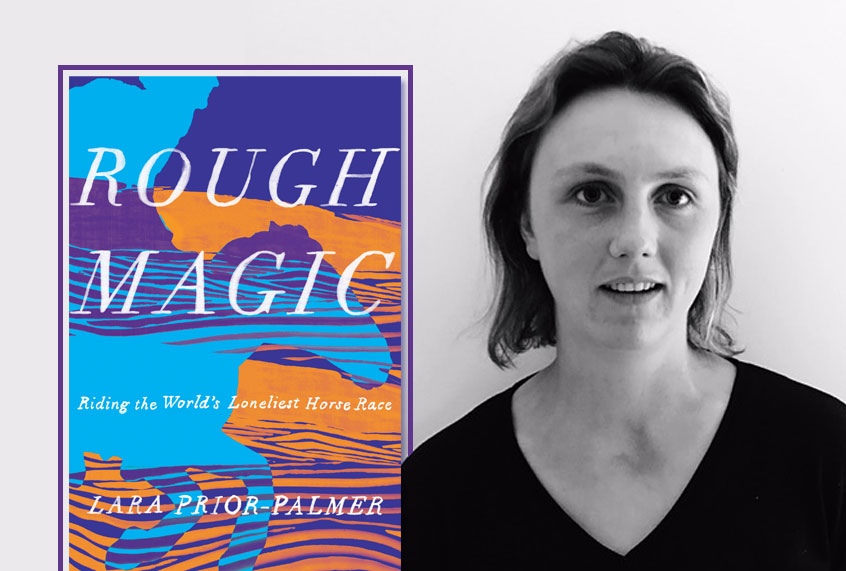

I spoke with Prior-Palmer last week by Skype, in advance of her U.S. book tour dates, about competition, the perks of being an underdog, and how she wrote this book. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

The level of preparation that you took for this race was quite different from a lot of your competitors. How prepared would you say you were for the race physically and mentally once you embarked?

I was always going to be a bit advanced, I think, because I was young, and so even though I’d probably done the least physical training, I might’ve fared better than riders in their 40s and 50s just by virtue of being a 19-year-old. But mentally, I feel that the psyche is a very slow thing, it evolves at a subterranean pace. And for a race like that, it is a good idea to have thought about doing it many, many, many months in advance to prepare your heart for what is going to be a drastic change in purpose, even though it’s only for ten days. And I had not done that.

You also have a bit of a self-deprecating style of writing, which is why I asked.

It was hard to say how prepared everyone else was. Some people aren’t self-deprecating. It’s certain that I had streamlined my life with the Derby as my aim for about four weeks before it, and in a very intensive manner. And perhaps that doesn’t come across in the book, but it was taking up a lot of my consciousness. Once I declare I’m doing something, I have thrown myself in the preparation.

I would have been, I’d say, mentally prepared, or mentally naturally inclined to enjoy the chaos the race was going to give us. But [I was] mentally unprepared probably for things like rain — that I hadn’t thought about.

The sense was that I was viewed as, and I do come across as a loose end, and detached, but I was viewed as pretty much to have rocked up accidentally, like [I walked] into the wrong party or something.

There’s something magical that happens about being an underdog, about being underestimated, because you get a lot less scrutiny at first than Devan the Texan [the frontrunner who becomes Lara’s chief rival] who comes into the race declaring that she’s going to win. Did winning such a high-profile race, as a person who was not expected to win, change that for you in general, in your life?

I think yes. It does make me slightly collapse inside when people say, “What’s going to be your next race?” [It’s] a metaphor for, “What are you going to do next?” I don’t know, just breathe?

I’m about to give a TED Talk, actually, this week on about how we monumentalize bravery, and think it has to be this big thing that we go and run a marathon or ride a race for, but it can be an everyday practice. But we just engage our bold modes while we’re doing admin and it can be exactly the same as sitting on a Mongolian [horse].

But it’s also the case that I probably haven’t been harnessed by anything as much as the race harnessed me. Somehow it had a magical pull on me. And I don’t ethically think that the race is an important thing, but ethically think that pushing the whole of yourself into anything is a truth that matters. By the end of the race, or the middle, I was just galvanized, all of me. So has that happened since? Yeah, maybe when I fall in love that happens. I don’t know. What are you going to do next? It’s annoying when people think that you can do anything because you rode horses across Mongolia.

It’s true that when other people have more faith in you, you probably end up having more ability to do things, because the simple fact of confidence makes you literally more able. But then I was always quite sly. I liked appearing detached and relaxed, and then getting things done anyway.

You mentioned that there was the point where you really did decide you were in it to win it. The focus of the book then changes once you realize that you are not in the back of the pack, but really quite up close, in that top five to seven, and then you start closing in on Devan that you actually want to win. Do you think there’s a fierce latent competitor inside of all of us, all the time, just waiting for the right moment to come out? Or do you think that that is a temperament thing that varies by individual?

I don’t believe in human nature so I don’t think we’re all born with one state of intuition or perfect . . . it’s like I was saying, we all have a bold mode. Probably, we all have a competitive mode, but I don’t trust it. I really don’t. I mean, we live in a very competitive culture. Capitalism promotes competition and production, and often competitive spirit comes from a place of irritation or hatred, such as mine for the race.

I think being competitive gets sold as being like wow, what grit to get yourself going, and that bit. I think it’s harder to work through your competitiveness and see what’s behind it, or what you really need. What you’re really after is some delicate attention really, or need for security because you’re fearful of being insecure. If we could really get to the bottom of why we’re competitive in any situation, I think we might feel more at ease in the world.

I wish I had talked more about that in the book, actually.

And there’s a difference between being competitive with yourself, which is to say, I’m going to finish this, or I’m going to do it again and I’m going to do it in a shorter amount of time, versus being set against other people so that there can only be one winner. In the end of the book and the race, you and Devan are very close in time to one another and then something happens that decides the end of the race. Do you think we’re socialized or trained to work harder to try to beat somebody else, or is the competitive spirit more pure when you’re just fighting against yourself?

Either of us could have won. It shouldn’t really be significant, but I did. But obviously this wouldn’t be a book, I don’t think, if I hadn’t. Which is a shame, but it’s true.

Because people want a winner. Right?

Yeah, why do people want a winner?

It’s such a production-seeker culture that I think we’re already [focused on] so much: future, future, harvest, harvest, prepare, prepare. Not so much wow, I’ve got enough as I am, everything’s already here. So, am I competitive with myself? I am in the sense that I want to paint a more truthful painting, write a more evocative paragraph, run without injuring myself, care for my friends, in a way that they want to be cared for, then I am competitive in that way by striving.

Competition with other people, I don’t think I go in for that really anymore. But I certainly did at the time of the race and it definitely fueled me. It was how I had been brought up. I was very competitive with my brothers at sports; I loved being better than them, especially as the girl.

Speaking of writing a more evocative paragraph, the level of detail that you capture in the book is really breathtaking. For a reader it’s delightful, and it’s also surprising because you’re on the back of a very fast-moving horse most of the way. You’re just speeding by. So, were you taking detailed notes along the way at every stop? In the Winnie-the-Pooh notebook you write about bringing?

I never thought of myself as a writer, although in moments of loneliness I loved to write letters to people. I wasn’t a girl at school who wrote and wrote and wrote, and I certainly didn’t take Winnie-the-Pooh with me in an effort to write a book in it. Even when I wrote everything that happened down after the race, I was simply doing it because I couldn’t believe how much of it I remembered. How fresh my memory was. I felt I had to put it all onto paper. It was only months later [people asked], “Oh, did you write a book about that?”

I wrote on the first day three sentences in Winnie-the-Pooh, four sentences maybe, because we had only ridden for ten hours that day as opposed to the normal thirteen and a half. And then, the next night, I think I wrote two sentences in Winnie the Pooh about the day, about how I felt just so exhausted. And the following day, I might as well say, I had written one or two words. This is always at night, never had time at the stations, you never had time to write. It was the last thing on your mind that writing is something you want to read through when you want to live through something again. I didn’t need to live through it again because the single experience is so strong.

I’m very curious about what being in that state of extreme endurance, and physical and mental exertion, does to our powers of attention and concentration to the world around us. Were you surprised that you remembered so much of the physical details of the landscape and such? You describe it so beautifully.

Total shock, because you think it would be the inverse. You’ve been in so much pain and so exhausted, the last thing you need is the memory of all of it. But, instead, yes there was some aliveness, as they say, a wholeness within me. I brought all of myself to the table.

Even when I didn’t remember something specific, I was able to re-enter the memory. Go back, visualize the space. Smells, even those are so evocative in my mind . . . you become an animal and an animal memory overtakes you. Which, I think, animals probably have very, very accurate sense memories. I don’t know. But that’s what I felt I got. It wasn’t like cognitive thoughts. For example, I could never remember any of the things that I said on the race.

I can remember a few of the things other people said, which are in quotation marks. I didn’t have memories for words or things, but it was very visual — all the feelings of each different horse, like the ingredients in them.

Was there one particular pony that stands out that you felt a connection with? If you could go back and take one of those and be with one of those horses for a longer period of time, was there one that stands out to you?

I’m laughing at the gray in the last day who is supposedly really fast. If a horse was going to be really fast it was usually really difficult and dangerous to get on. And this gray was still so calm, composed, beautiful, like he was about to play a concerto or something. And then the herder dropped the rein, let go of the shoulder. He still didn’t do anything. He didn’t move. Usually they’re just galloping. And then I said choo, choo, the noise you make, and he disappeared beneath me, and we were gone so fast, with such complete contrast. And so he was incredibly memorable. And he was calm! I was also ill and very sensitive to his calmness, because I hadn’t eaten for quite a while by that point.

My first answer would have undoubtedly been The Lion. I think he’s the fourteenth or the fifteenth horse [I rode]. And he was just drawing his energy from another source — not quite a horse, you know what I mean? It’s not because he was so fast, but the way in which he was so fast does reveal that he was Other, in a special way. We got to the mountain pass, and he decided that we didn’t need to walk and started jiggling his way up it. And I thought, and he’s carrying me, and he was just so ahead of me all the time. He was one of the horses it felt like he was doing the race for me, and I was just riding, literally, just riding the wave.

Was it different coming home and then getting on a horse that you were more used to? Honestly, I don’t know anything about horses.

I haven’t told anyone this, but the family holiday that year — we usually went to Brittany and sit on the rainy beach every year, but that year, we wanted to be adventurous and decided we were going to the wild. We decide to go to Wyoming and stay with some people on a ranch. I think that was the next time I rode a horse. A big horse. They’re much bigger. The Mongolian horses are genetically horses, because their heads are big, but they are small in their bodies, although very strong.

I remember being put on a horse bareback, and then, the whole family sort of knowing how to bareback ride . . .”Yeah I occasionally do that. Aha.” I remember feeling incredibly insecure and clinging on with my thighs, and trying to live up to the horsewoman reputation. But almost falling off its shoulders as I pulled him up. Someone tried to take photographs of me cantering in the sunlight. We saw our photographs and I look slightly lopsided.