The very mention of this year summons indelible memories. Woodstock and Altamont. Charles Manson and the Zodiac Killer. The televised events of the moon landing and Ted Kennedy’s address after Chappaquiddick. The Amazin’ Mets and Broadway Joe’s Jets. The Stonewall Riots and the Days of Rage. Americans pushed new boundaries on stage, screen, and the printed page. The first punk and metal albums hit the airwaves. Swinger culture became chic. The Santa Barbara oil slick and Cuyahoga River fire highlighted growing ecological devastation. The nationwide Moratorium and the breaking story of the My Lai massacre inspired impassioned debate on the Vietnam War. Richard Nixon spoke of “The Silent Majority” while John and Yoko urged us to “Give Peace a Chance.” In this rich and comprehensive narrative, Rob Kirkpatrick chronicles an unparalleled year in American society in all its explosive ups and downs.

“It was a year of extremes, of violence and madness as well as achievement and success.”

—Barry Miles, Hippie

For a year that had so many amazing, startling, and culture-defining moments—the year that perhaps defined the era more than any other—it’s hard to believe that no one had yet written a book about 1969.

Humankind hurtled through air and space in 1969, the year of the moon landing and the inaugural flight of the 747. It marked the beginning of the age of Nixon and the Silent Majority, and it saw the effective end of Camelot with the Chappaquiddick incident. It was when American forces began the covert bombing of Cambodia and fought the Battle of Hamburger Hill, when the American people lost their innocence with the discovery of the My Lai massacre, and when they came together in the Moratorium and the Mobilization.

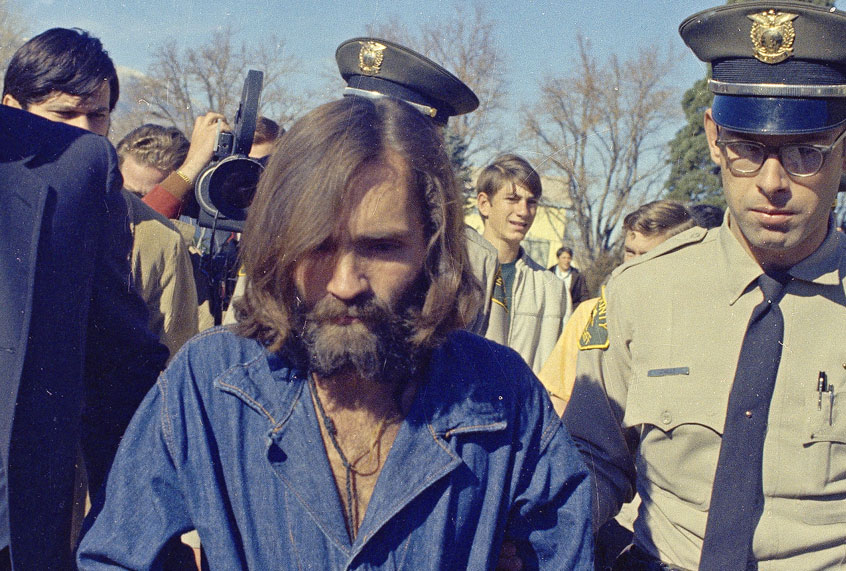

It was the year when America got undressed—figuratively and literally—on screen, onstage, and outdoors. Nineteen sixty-nine was the height of the Sexual Revolution, with “Portnoy’s Complaint” and “Oh! Calcutta!” and “Midnight Cowboy” and “I Am Curious (Yellow)” and “Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice” all speaking to the changing climate of morality and social taboos. It was the year of the commune, the year of nudity onstage, and the year of the outdoor music festival—highlighted by the generation-shaping Woodstock. It also revealed the dark side of the counterculture with Charles Manson and the Altamont Speedway Concert.

Musically, it was a year of firsts. The Stooges and MC5 released the first punk records, while Led Zeppelin’s first two albums and U. S. tour launched heavy metal in America. Miles Davis propelled jazz into a new age with the seminal rock-fusion classic “Bitches Brew,” while King Crimson set the mold for progressive rock with “In the Court of the Crimson King.” The Grateful Dead’s “Aoxomoxoa” and the Allman Brothers’ debut release gave us the initial offerings of jam band music and Southern rock. The Who debuted the rock opera “Tommy,” and Crosby, Stills & Nash and Blind Faith appeared on the scene as rock’s first supergroups. The Rolling Stones reached their creative peak, and, with their 1969 U. S. tour, assumed the mantle of Greatest Rock ’n’ Roll Band in the World.

Broadway Joe and the Jets scored an upset for the ages that cemented the merger of the AFL and NFL and led to the network deal for “Monday Night Football.” Tom Seaver and the Amazin’ Mets staged baseball’s biggest miracle. The year saw baseball’s future with the designated hitter, an experiment introduced that spring, and even more controversial, Curt Flood’s challenge to the sport’s reserve clause in seeking to become baseball’s first free agent.

The FBI declared war on the Black Panther Party, and the Weathermen declared war on America. The Stonewall Riots inspired the birth of the Gay Rights movement, and the Indians of All Tribes’ seizure of Alcatraz Island began the Red Power movement. The Santa Barbara Oil Slick, the Cuyahoga River fire, and People’s Park gave impetus to the Ecology movement. It was the year when the Revolution came to the suburbs, and when they paved paradise and put up a parking lot.

In a single year, America saw the peaks and valleys of an entire decade—the death of the old and the birth of the new—the birth, I would argue, of modern America.

For those who first came into consciousness in the beginning of the 1970s, as I did, there was a sense of the country having just gone through an enormous upheaval—a paradigm shift that the generation before us had witnessed first hand, through which we had emerged as if through the other side of the looking glass. It was like arriving at a production of “Hamlet” near the end of Act V: Hamlet lay poisoned on the ground, the bodies of courtiers lay around him, and as Fortinbras did, you wondered how things had gotten to that point. With this book, I set out not just to tell the story of 1969 in America, but also to examine the zeitgeist—literally, the “time spirit”—of this iconic, tumultuous, cataclysmic year. As Theodore Roszak wrote in “The Making of a Counter Culture,” “that elusive conception called ‘the spirit of the times’ continues to nag at the mind and demand recognition, since it seems to be the only way available in which one can make even provisional sense of the world one lives in.”

In reviewing the popular culture of the day, notions of the apocalypse appear with surprising frequency. I found references to the end-times not just in news stories on the armed takeover of Cornell University or the Days or Rage or the first Strategic Arms Limitation Talks, but also in reviews of Jefferson Airplane’s “Volunteers” and Sam Peckinpah’s “The Wild Bunch,” in the work of artist Ron Cobb, the chaos at the Altamont Free Concert, even in the fiction of John Cheever. The decade was one of the most turbulent in the history of the United States, and as it came to an end, an early form of millennial anxiety seemed to grip the country. The end of things was very much on the collective American mind at the end of the sixties.

But the sixties no more ended in 1969 than they began in 1960. As is implied by the bookend works of Jon Margolis’s “The Last Innocent Year: America in 1964—The Beginning of the ‘Sixties'” and Andreas Killen’s “1973 Nervous Breakdown: Watergate, Warhol, and the Birth of Post-Sixties America,” the sixties was not so much a period of ten years as it was a less distinctly defined period of cultural and social change during which America tuned in, turned on, dropped out, grew up, woke up, blew up.