Two years ago, I started an Instagram account to post comics, most of them arranged around the theme of men being rewarded for doing the least. I worked on the comics during my lunch breaks at work, posting them when I could for my few hundred followers, mostly friends and family. But the account quickly grew into something beyond what I’d ever imagined, and while it’s been an incredible journey, it’s also presented me with a stark case study in, ironically, the very stuff I was writing about when I started shouting comics into the void. Where are the nuances inherent in trying, failing, flailing at communicating with each other online?

Making work about men does get me very specific “feedback.” It’s usually easy to clock as “I’m functioning as a receptacle for your misogyny” and keep going. There is the blatant harassment, the type not “fun” enough to respond to or screenshot to prove a point. There is the objectively hilarious trolling, the kind I often feel compelled to engage with for the sake of comedy. There are the peddlers of “civil disagreement” — I like to think of them as trolls in tweed blazers, who cloak themselves in academese and are “just trying to have a measured conversation.” (Block them and it’s censorship; argue back and you’re a “man-hating feminist” hellbent on destruction.) And then there are the “save the spiteful woman from herself” messages, dripping with false positivity and disguised as concern for my well-being. Those almost always come from other women.

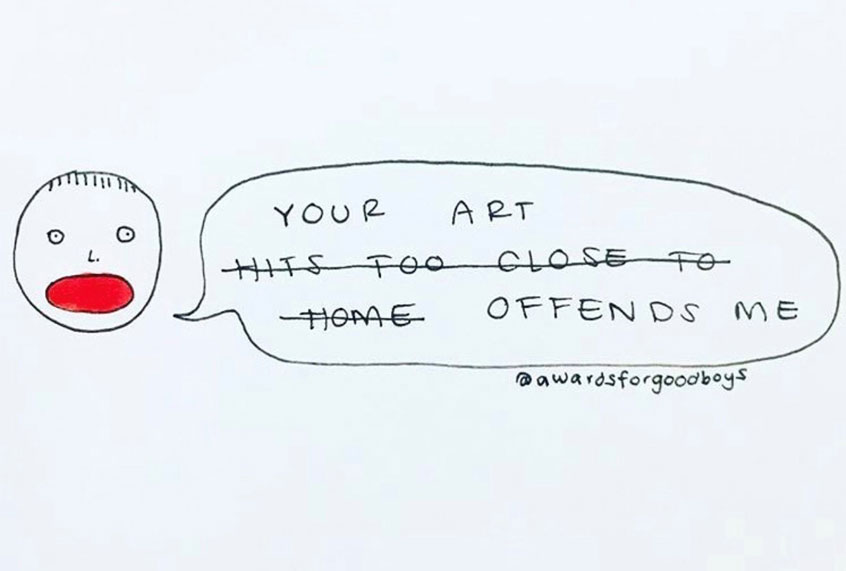

The subtler type of trolling, the kind that purports to be — and sometimes is — actual constructive criticism, is more complicated. I’ve lost the ability to tell what people expect in these moments, and more so, don’t know what it is they deserve from me. A measured response? What does that mean? I’m a public figure — of a sort — who satirizes everything around me all day. Do I owe them a genuine response? I ask myself a question in moments like this, trying to gauge whether my tendency to engage snarkily is warranted, whether it’s actually funny or just rude. Are they being misogynistic or am I being an asshole?

It’s far too simple a question. How could I possibly know? It often seems like both. Discerning what exactly anyone intends with their comments and questions on my work has become increasingly difficult. And as I’ve grappled with it, my ability to maintain some sort of composure has visibly eroded.

I spent a lot of the first year of my growing online visibility engaging with the negative feedback. Maybe too much. When you have a platform, people forget that you are a person. Even the non-hostile interactions on my page prove that over and over again. People will tag their friends with sentiments like “you’ll hate this account” as if I can’t see it. In the early days, I would screenshot these comments and make them into posts, or respond with something witty. But often this would turn into a pile-on I didn’t intend, or even worse, merely serve to encourage the trolls who were only looking to provoke a reaction. And it worked. I became hardened by it, expecting them even, a synapse always firing and ready to spring into action across all platforms, because trolls will find you on every platform. Not even your LinkedIn is safe.

I’ve crawled towards developing a code for what is worth it — what is educational, and what is me merely flexing my intellect or humor or ego. It’s evolving, and it’s messy. But I can’t help it: I still respond to many, and I still re-post them too. I try not to let troll commentary eclipse my actual art, but it often does. People are more excited when they see me engaging with a “real troll” than they are about my nameless reflections on broader patterns in our world, and as a person who depends on said engagement to keep doing my work, it’s a Gordian Knot that often leads to heckling the trolls right back.

Is the tendency for others to read this as me being an asshole, and for me to believe them, reflective of our expectations for how non-men are meant to behave in public? Or is that just my reluctance to accept that I can behave badly too?

It can, and does, feel like a loss to voice the intricacies of my failings in a world where so many people are failing so much louder and so much harder with catastrophically more devastating results, especially those who are forever inoculated from taking responsibility.

But it’s not really a loss. It’s just a depth that many who are forever inoculated from taking responsibility can’t achieve. (Am I being an asshole? Yes. Am I right? Also yes). But I love nuance, don’t I? I love thinking about failures in communication and the responsibility I have as someone with a platform, even though I know most men with a following never deign to do such a thing.

But their actions cannot be the roadmap to mine. I can make a choice about how to behave, I can question out loud how surreal it is to be just a person who is now a public person, to ask what I’ve lost in this rise, to look at how the knee jerk reaction to respond to trolls isn’t a phenomenon limited to me but one I can personally reframe. I can continue to accept that sometimes the answer to my oft-asked question is, in fact, yes: I’m being an asshole. And that as long as I know, and can own that, that’s fine by me.