Last summer I ran away from home. And, with Dead & Company having recently started their summer tour, I’m planning to do it again. Because sometimes we have to run away from home to get home. And I think many of us are feeling homesick right now — for generosity, freedom and community. For real human connection. We’re especially homesick to be present with each other.

The Grateful Dead — and now, Dead & Company — has been a sort of home to many of us for many years. After Jerry Garcia died in 1995, we were adrift. But something fortuitous has happened in the last few years, now that they’ve reconvened as Dead & Company. And it seems to have happened just at the right time. As Mickey Hart, one of the Dead’s long-time percussionists, told me last summer, “We’re living in an incredibly difficult, worrisome, scary time. Where everything is being turned upside-down. And people need a home base. From where I sit, I could be doing nothing better than to be able to bring that feeling of home to so many people.”

In 1988, I saw my first Grateful Dead show. I was 16. And I climbed right on that figurative bus, which took me to scores of shows across the country over the next four years. The Dead tour became my traveling home when I wasn’t at school. In the last week of August 1991, with a carful of mostly strangers, I skipped my first week of classes at the University of Colorado to drive a thousand miles to see a Jerry Garcia Band show in Squaw Valley, California. In a wood-paneled station wagon — without a plan, tickets, or a place to sleep — we drove until we were too tired to drive any longer, pulling off the highway into the Nevada desert where we slept on the still sun-warmed ground, under the stars. When we arrived in the bustling parking lot where thousands of Deadheads had already gathered, we instantly felt relieved, accepted and embraced. I think we all were feeling homesick during our first week of college. So we, this bunch of strangers, went home together to a place to which none of us had ever been.

I knew I loved the music. I knew I loved the people. But it would take me another 30 years to understand exactly what it was about this world that made it so meaningful to me.

In June of last year, with less than a week’s notice, my husband Paul and I scrapped our plans to go to Europe for our summer vacation and decided instead to follow the Dead for their entire West Coast tour (and some of the East Coast too). Over the next few weeks, we drove 4,000 miles in a rented truck, slept in 14 different places, ate at truck stops, and saw about a dozen Dead & Company shows.

Before we left, I was at a particularly low point — feeling alienated and broken by the destructive and seemingly relentless attacks and fights in my professional world — and in the world more broadly. It was my Australian husband, to whom the Dead was an entirely new experience, who suggested: “Let’s do what we know makes you happy — see as many Dead shows as we can.” It wasn’t meant to be life-changing; it was meant to be an escape. From myself. From the world. We’d go back in time to my carefree Deadhead days. But not long into the journey, I realized that I wasn’t escaping myself; I was returning to myself. I was going right back home. Right back to my roots. Right back to the things that have always been and will always remain my core values and beliefs and passions.

The things I feared were frivolous during my young Deadhead days, I began to understand in an entirely different way. They’re the very things I study, write and teach about: presence, listening, generosity, trust, authentic self-expression. The building blocks of healthy human interactions, cultures and communities. The things that we now know, through abundant scientific research, lead people and societies to thrive.

At this point, you might be scratching your heads.

For many people, when they hear “Grateful Dead,” they hear the “dead,” but not the “grateful.” And so they inevitably categorize the band (and its fans, Deadheads) as nihilistic. Scary. Something they should protect their kids from.

But the true meaning couldn’t be less sinister. In fact, it’s an allegory that precisely captures the essence of the band and its followers. The “grateful dead” is “the soul of a dead person, or his angel, showing gratitude to someone who, as an act of charity, arranged their burial.” As Jerry Garcia once described this symbolic narrative, “grateful dead” comes from a folk tale “of a wanderer who gives his last penny to pay for a corpse’s burial, then is magically aided by the spirit of the dead person.” It is about strangers communing. “Strangers stopping strangers, just to shake their hand,” as the lyric goes from one of the band’s more well-known songs, “Scarlet Begonias.”

That value, bounteous presence, runs deep throughout the Dead community, beginning with the band itself. To understand how, you must first know that every show they play is totally unique, made up of two 90-ish-minute sets of songs, with jams between many, from their catalog of more than 500. In the band’s 50+ years and more than 2,500 shows, no two concerts have been alike — literally. That means that they give every single audience a gift: a three-hour live musical performance that has never been performed before and that will never be performed again.

To pull off these unique sets of songs threaded together through improvisation requires an exquisite interconnectedness among the band members, one that engenders both synchroneity and freedom. One that is built on trust.

Hart explained to me how they make the magic happen. “We’re talking to each other. We have all these conversations going — in the rhythm, in the melody, in the nuances of everybody’s feelings there that night. If you’re aware of your partners’ feelings — really listening, really really closely — not trying to overplay him or anything like that, trying to form a group instead of a bunch of notes and soloists and playing parts — then it happens.”

They must be able to hear and feel, lead and follow one another. As a band, they must be wholly and generously present. And by doing so, they create a musical experience that can be bountiful and liberated, sometimes even transcendent.

And while a bunch of Deadheads might superficially appear primitive, their behavior is enlightened. Bounteous presence is expressed in their interactions not only with each other, but with most everyone they encounter: skeptical locals in the towns where the band is playing, people taking tickets or serving concessions at the venues, hotel and restaurant staff members, and so on. Deadheads notice people, look them in the eye, and see them. They chip in, clean up after themselves, offer what they have to those who need it, and express gratitude to those who have given them what they needed. As the late Jon McIntire, who managed the band for two decades, said in a 1988 interview, “I have a lot of faith in the gentleness of Deadheads.”

Their bounteous presence creates a sort of kindness serendipity that wraps around the community as a whole and makes things feel magical. Things work out, they fall into place, because people are paying attention to and caring for each other. They are creating a virtuous cycle that seems to bring out the best in everyone. What feels magical is not actually magical: rather, it is exactly what arises when people agree to behave in a way that is socially enlightened — a community where people feel safe, generous and free. As I always say, presence begets presence, and there are fewer places where this is more true than at a Dead show. It is a communion.

This is exactly what I study and teach about. The power and conveyance of presence — what happens when we show up as our authentic, unguarded selves, and we are able to hear each other. And when we are able to hear each other, we become present together. As a band. As an audience. And the band with the audience. Hart agrees. “When we’re in the moment and entrained with each other, the audience feels that. And that’s the feeling you get when you’re in the now.”

As I wrote in my book “Presence,” “When a musician is present, we are moved, transported, and convinced. When a musician is present, they bring us with them, to the present.”

So, when Jerry Garcia died in 1995, 30 years after the band first came together, we weren’t just grieving the loss of a person; we were grieving the loss of our most beloved community. It was as if, suddenly, our hometowns had just been wiped off the map. Even for those of us who had moved far away, who hadn’t seen a show in years — those of us who took for granted that we could always go back when we needed that love and comfort — the blow was stunning. Because we collectively realized: none of us could ever go back home.

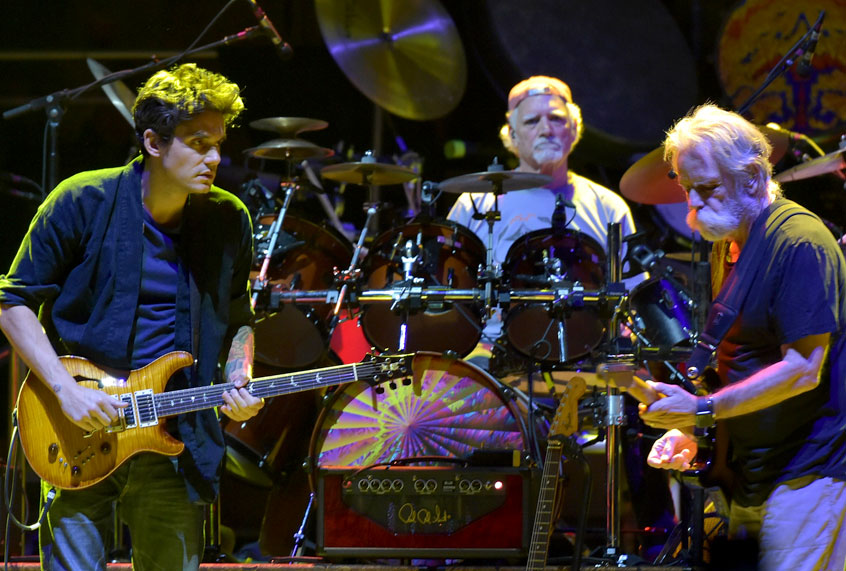

After Jerry died, some other outstanding guitarists stepped into his spot and over about 18 years, the band sporadically reassembled in several different formations. I saw all of them, and they all sounded great. But to me, and to many others, I believe, none felt like home. And then, in 2015, something almost unbelievable and certainly unlikely happened: they came together in a new way that did feel like home. Original members Hart, Bob Weir (guitar) and Bill Kreutzmann (drums/percussion) were joined by esteemed younger musicians Oteil Burbridge (bass guitar), Jeff Chimenti (keyboards) and John Mayer (guitar), calling themselves Dead & Company. All three musically virtuosic newcomers came to the band and music with openness and gratitude, setting aside individual egos to join something bigger. And all three of the original members, who created this thing and have been playing together for more than 50 years, received them with openness and gratitude, also setting aside individual egos in the interest of making something greater.

Guitar prodigy John Mayer, whose arrival was the most surprising to Deadheads, accomplished the critical thing that no other post-Jerry guitarist had been able to do: by bringing, in earnest, his fullest, most authentic, spirited, unpretentious self to his bandmates and to the music, he plays with deep respect for Jerry, without trying to be Jerry. And that has liberated both the musicians and the music. All members of the band seem to have embraced each other, creating an interplay that we haven’t heard in decades. On stage, they are entirely present, playful with and supportive of each other, demonstrably admiring and affectionate, delighted for a bandmate when he plays an especially incendiary riff. As a result, they have built a place for the rest of us to come home to. It is the most beautiful reincarnation: our community, our music, our band — but in a different form. The same, but different in the exact ways that fit where we are now.

While they are communing onstage, the fans are communing offstage, mirroring the same intergenerational dynamics. Older Deadheads are not only reconnecting with each other; they are also shepherding in a new generation of Deadheads, without any of the You’re-Too-Young-To-Understand attitude that one might expect. And those younger Deadheads are infusing the community with excitement about their newly discovered home. They too were looking for something. When you put these things together — the band fully present, the audience fully present — you get a kind of visceral joy that springs from feeling connected, free and understood. It all still seems a bit miraculous, and I don’t take it for granted for a single minute.

When I look at all of this from 30,000 feet, I can’t help but wonder: Are we all in a moment of greater need of community? Of hometowns? Of bounteous presence? Does this help to explain why the Dead are selling out shows and booking the largest venues every single year, an unusual accomplishment for any band? And does it help to explain why these talented musicians — each of whom could be enjoying the glory of solo shows — have instead come together to build this new home?

After only a few shows last summer, Paul said, “Now I understand why so many people who started following the Dead never left, even when the tour was over. They were already home.”

Many of us are feeling a bit homesick right now. If you’re an old Deadhead, a new Deadhead, or even if you’re just open to the idea of seeing the Dead play, please catch a show during this summer tour. (Here are the upcoming dates.) And enjoy the collective presence, where phones are put away and no one’s asking you what your job is. If it’s not your thing, that’s OK. But I encourage you to return for a visit to your own home away from home. I can tell you that for as long as this band is playing together, I will be going home as often as I can.