In 2009, I was sexually assaulted by a man I was seeing off and on, which led to an unplanned pregnancy. We had slept together several times. I didn’t have insurance and I wasn’t on birth control, so he had never ejaculated inside of me until this one afternoon he did without warning. I hit him hard on the arm and made him leave. I didn’t know what he had done was considered assault, akin to “stealthing” — the non-consensual removal of a condom — and didn’t know there was language for what had happened to me. Men still do things we don’t even have names for, which make consequences more easily avoided.

I peed immediately after. I did not get a morning after pill. To be honest, I didn’t know how, and 10 years ago it wasn’t as ubiquitous as it is now. I also probably couldn’t have afforded it. In addition, I had very little sexual experience since I had just, six months earlier, divorced the first person I’d ever slept with. The person I’d saved my virginity for, as we were both Evangelical Christians. I was 27 years old, the same age as many of my Christian acquaintances who already had multiple children. And I had always been someone who worked with children and dreamed of being a mother.

My job was about to end. I had just finished my MFA in Creative Writing, which left me $75,000 in debt with no job prospects to speak of after the collapse of the economy. My family lived four hours away and was already disappointed enough in me for quitting teaching to get a terminal arts degree and for getting a divorce, something else the church frowned upon. I wanted nothing to do with the man who got me pregnant. It was a terrible situation to bring a child into, any way you looked at it.

I had been so lonely as my marriage and graduate school ended simultaneously, spiraling into a depression that mostly included eating whole BBQ chicken pizzas alone in bed while binge watching “Six Feet Under” or “Grey’s Anatomy” and sobbing. I wanted so badly to be in love again. Or rather, to have someone in love with me. I was so eager and so naive I dated a long stretch of horrible people. I wanted someone to take care of me. After years of stunted emotional growth due to the spiritual abuse I experienced at the hands of the church, there were parts of me that were still very much like a child. Not the childlike wonder I try to cultivate now, but childlike fear and attachment. I clung to adolescent ideas of what relationships looked like.

A close friend came with me to an appointment where I saw my ultrasound at six weeks. A dot on the screen that looked nothing like a person. There was a part of me that wished I had a supportive, loving partner by my side. I imagined the joyful tears, the deep bond forming. Scenes from television shows and movies.

I scheduled an abortion for the following Friday.

That night, I went out to support another friend’s band. She had immediately expressed her support for abortion and didn’t make it a big deal, which was comforting for someone like me, who found most life decisions to be big deals, cosmically or spiritually. I dressed up. I flirted with one of her bandmates, all the while in the back of my mind feeling weird and deceptive. I ordered a large beer. Before the set started, the man who assaulted me showed up at the venue. I hadn’t spoken to him since I’d kicked him out of my house, but it was clear he had stalked me and come to the place he knew I would be. My friend helped me avoid him for most of the night until he disappeared. I felt even more secure in my decision to terminate the pregnancy, as well as to not include him in the decision.

Only my two friends knew about the pregnancy or my appointment. Having very little experience or education on the subject, I was extremely afraid. Also, part of my indoctrination still lingered, the religious belief that abortion was wrong, even though to anyone else I would say I was pro-choice. Really, I was pro-choice, just not for me — because I thought I was supposed to know better. Or I still had not deconstructed my religious beliefs far enough to believe there wouldn’t be some eternal punishment.

I hate vomiting almost more than any other kind of sickness, and after the first time I was overcome by nausea, I bawled on the bathroom floor. I wanted my mom. Spiraling and panicked, I decided to call her. I can’t remember how the conversation opened, but I do remember saying, “I’m sorry,” and “Please don’t be mad” through tears. I was 27 years old. I was not a child, but I spoke as though I had broken her favorite vase. Not as a woman who had been sexually assaulted and had bodily autonomy. I wasn’t sure I had bodily autonomy. I wasn’t sure there wasn’t some divine punishment. Or as someone who already struggled with depression, some emotional or mental toll that would leave me completely incapacitated.

On the phone, my mom cried too. She brought up adoption, which I knew I could never do, and which I don’t believe any woman should be forced to do. Part of what gets people through pregnancy, through the pain and discomfort and fear, is the knowledge of what comes after. The fulfillment of a dream of having a child. Some women act as surrogates and are paid, but are never under the impression the child they are carrying belongs to them. What do the women who give their babies up for adoption get in return? A sense of righteousness or martyrdom? From what I can tell, it costs thousands and thousands of dollars to adopt a child. Many adoptions happen in other countries, while our foster care system in the United States is overburdened with unwanted children.

There is a line at the end of Rilke’s famous poem, “Archaic Torso of Apollo,” I always think about: You must change your life. Depending on which word you emphasize, it can carry different meanings. You must change your life. You are the one responsible. You have agency. Or: You must change your life. It is imperative that your life change. I felt both of these. I hated my life. I wanted something to change. And here it was. Something major. There would be no going back to this life. The unknown looked better than the current known. Home, with its many complications, sounded like salvation. A baby sounded like love.

My mom said if I had the baby, they would support me. I could come home. I told her I’d keep the baby and I cancelled the appointment.

Then I told the father, who was weirdly overjoyed. In hindsight, I remember him telling me his previous serious girlfriend had two abortions. Another time, he told me about a dream he’d had about us, in which I was pregnant and he was fooling around with me in a dressing room at a store. I had laughed it off at the time.

He said he wanted to get married. We were sitting on the unmade bed in my tiny bedroom. I could see our reflection in the vanity mirror. He tried to kiss me and I pushed him away. I said we could be friends. I thought I would need the financial support. And even though this man had hurt me, there was still this idea, deeply ingrained in me: the father deserved to know his kid. The child needed to know its father. This is the kind of thinking that allows men to sue their teenage girlfriends to prevent them from getting abortions; the kind of thinking that informs legislation that could force a woman to give birth to the baby of her rapist.

For about a week, he texted regularly and tried to take care of me. We went to a movie once and again, he tried to get romantic. Slowly, the attention tapered off when he realized I wasn’t going to marry him. Ever. And that he would have to pay child support. Eventually he stopped all contact after I tried to get his insurance information to help with my doctor’s appointments so I wouldn’t have to go on government assistance.

Almost 10 years later, I have still never heard from him. Thanks to social media, I know he is married with a good job, and they own a home. I don’t know if his partner knows. I don’t know if I ever want to hear from him. I don’t think I do. On my child’s birth certificate, in the father space, he is listed as Unknown.

My mother, the daughter of a truck driver and a struggling homemaker, the third child of four, was only able to afford college on an ROTC scholarship. She was studying to be a nurse. She was dating a friend of her older brother’s, and they were in love. When she got pregnant, she also thought about abortion.

When she told me this once, she looked ashamed.

My dad asked her to marry him. They got engaged, and she dropped out of college. This was in the early 1980s, when many of their friends were also getting married and starting families young, and in a small Western Pennsylvania town, you could support a family on one salary, even at a trade job, which my dad had in a glass factory where he’d started working at sixteen.

My parents did not become Evangelical until their 30s, after a difficult season in their life: My dad’s plant had shut down, putting us in financial jeopardy, and their marriage was struggling. They decided to leave their small town for a slightly larger one and start over, in a way. I was 13. I hadn’t yet had my period. My parents took us to church and I was pulled into it all. I was a lonely middle schooler who had just left all of her friends. Weird as fundamentalism was, the idea of built-in community was appealing.

We were living in a beat-up townhouse where I shared a bedroom and a bed with my 12-year-old sister, and we all shared one small bathroom. My mom took on a job as a maid because it required no experience and she was able to use the company car to drive to and from work when we couldn’t afford a second car payment. This was the first job she’d had besides babysitting in all of my childhood. We qualified for reduced-fee lunches. I wore the same outfits over and over each week, whatever was cheapest and on sale or handed down. My parents bought a house, but without a college degree, my dad’s job stagnated, and mom was making just a little over minimum wage, as well as beating up her body daily. We lived paycheck to paycheck. We cut corners wherever we could. We were always safe; we never went hungry. We were lucky.

I got my first job at the end of my senior year of high school, at the same time I got my first car, a 1988 Mazda 626 I drove into the ground. I got a partial scholarship to college and took out loans for the rest. My parents filled out a FAFSA with their financial information, even though I would be the one to bear the burden of paying it all back. I couldn’t afford dorms, so I lived at home, which strained our relationship because they couldn’t see me as an adult when I was living under their roof. When I wasn’t taking a full course load, I was working or volunteering at church as a youth group leader.

When I moved back home, pregnant, I had to go on welfare. To qualify for benefits, I had to fill out forms and go to various offices. I had to prove I was working, and I had to prove I was in need .I worked as a substitute teacher as often as I could, up to the last two months of my pregnancy. I was able to go to doctor’s appointments. I was able to get healthy food myself and eventually my child. I do not take this for granted. Without it, I could not have survived, even living at home with my parents and not paying rent. This is the kind of funding pro-life politicians want to cut, building up the myth of the “welfare queen.” I was 27 with a master’s degree and had never been without a job since high school. I was the first one in my family to go to college and finish. Two degrees. Those were supposed to be my bootstraps. Instead, they were more like cement shoes.

“What if your mother had aborted you?” is a question that people like to ask each time we step up to the precipice of a Roe v. Wade reversal. I wish someone would ask me to my face so I could tell them: “Sometimes I wish she had.” Now that I know what it means to carry a child, to be a mother. While I am glad my mother never had to go to war to pay back a debt — war, to me, is about as anti-life as you can get — I wish she had been given a college education. I wish she had been able to get to know herself more. I wish she had been able to explore the world or even just the world around her. I even wish, sometimes, because it’s been difficult so very often, because making a decision about marriage when you are still just a teenager isn’t necessarily healthy, that maybe she had been able to experience relationships and love and sex outside of just my dad. Even though my dad is a good man who did the right thing. When I got married at 22, four years older than she was, I was still nowhere near ready to be a wife, let alone a mother.

Maybe an abortion could have simply been a pause.

She wanted children. But she could have gotten married and had them later. After. Maybe the next pregnancy would have still been me.

How does anybody know who you are until you exist?

All of this is hypothetical. It has no bearing on the now. I am the person I am now because they are my parents. The choices she made are what made me too.

I can say this without reservation: I thought about aborting a pregnancy, but I never thought about aborting my daughter. My daughter only exists because I chose her, chose to put my own body at risk, chose pain and fear and tiredness you could not fathom and stitches in my most sensitive parts and raw nipples and a constant low-grade fear of death now that she is outside of my body. Now that she is a person.

We do not become who we are in a vacuum. She is who she is now (who she is becoming, because even now, she still needs me) because of the way I am raising her and the world that she lives in. I do my best in a country where, for just one example, a man’s access to a gun for hobby or sport is more important than her life. In a world where I, too, live paycheck to paycheck. Where the government takes our family’s tax refund to pay for my college loans, which I have been unable to pay for the past 10 years due to a lack of career opportunities and the exorbitant cost of childcare. The money that was meant for camp or childcare so that I could be able to work this summer. Instead, I am working from home, trying to keep her entertained at best, neglecting her to screens at worst, while barely scraping by on my partner’s salary. She won’t get to make friends and learn new things. She will likely have more time in front of screens than is recommended. And I feel responsible and guilty. But also helpless. I worked as hard as I could. I did everything they told me to do. I did everything right. It has never been enough. It will never be enough.

But I don’t resent my daughter, and partly it’s because I was able to make a choice. I did a sort of cost-benefit analysis. I was influenced by my upbringing and circumstances, but ultimately, I made the decision to bring something good out of something terrible. While I was weak in many ways, I had the kind of support that made me strong enough to believe I could do it. There are so many people who don’t. Even if everything else was perfect, without the safety net of love or family or government assistance, I wouldn’t have made it. I’m not sure I’d even be alive. If I’d been forced into carrying a child because of the threat of punishment, I think I would feel very differently about my child. As it stands, I love and am grateful for her in a way I cannot fully express or comprehend.

I decided to have another child four years later, once I was remarried. I wanted the experience of choosing. I was lucky not to have fertility struggles, as many women do. Other than several months of debilitating morning sickness, the pregnancy went fairly smoothly. But at 33 weeks, there was a problem. I started bleeding and cramping. They couldn’t figure out what was wrong. For both the baby and me, they decided the best option was to induce labor, seven weeks early. They gave me steroids for the baby’s lungs and then pitocin. I gave birth to a five pound baby who was immediately given a breathing tube, so I couldn’t hold her. They only held her out so I could kiss her head before they checked her vitals and hooked her up to the incubator in the NICU wing.

We spent three weeks going back and forth to the hospital with another child at home who wasn’t even allowed in the NICU. It was scary and draining. It was not what I envisioned as we got the nursery ready or made plans for my family to come and stay. I was pumping almost all the time so I could take milk to her. It took an additional week before we could hold her because they couldn’t get one sensor in her foot, where it normally went, so that had to put it in her bellybutton.

The good news is that she has just finished kindergarten and is perfectly, amazingly healthy. But the medical bills we received for her time in the hospital, even though we had insurance, were debilitating. I did everything I was supposed to do, and still, there was a fluke. I could have died. My baby could have died or been seriously delayed or debilitated. But everyone wants to talk about pregnancy and birth as though it is something simple. Even if you are ready to change your life, even if you plan it, sometimes there are complications. There is a lot of risk involved with pregnancy, especially in our country where the maternal mortality rate is actually growing instead of shrinking. Having a child can alter your body and mind and put you at risk in the way a safe, legal abortion absolutely cannot.

There is a cost to becoming a mother. There is a cost to a child when their mother is not ready, not supported, not healthy, the victim of an assault, or even dies in the process of giving them life. There is a cost to sending your child to school each day and fearing they may be traumatized, or worse: never sent home again. There is a cost to watching your child suffer. There is a cost to suffering yourself in order to try to keep your child from suffering. This is what perpetuates cycles of poverty and abuse and neglect, which are real traumas happening to real, living, breathing children who can feel and experience them.

My daughter’s body became her own the moment the umbilical cord was cut, even though she needed me to survive. We all need so much more than just survival. Children live when mothers are supported. Children thrive when mothers are able to make the choice to become mothers when the time and circumstances are the best for them. Women thrive when they are able to make choices about their own bodies. And this terrifies the men in power who want to keep that from happening.

The Evangelical church leans on a particular verse from the Bible when arguing for a ban on abortions. Psalm 139, verses 13 and 14, which say: “For you created my inmost being; you knit me together in my mother’s womb. I praise you because I am fearfully and wonderfully made; your works are wonderful, I know that full well.” A writer myself and a voracious reader, I enjoy poetry (see: Rilke) and can appreciate the beauty of language. The Psalms are poetry. The Psalms are metaphor. The Psalms are not law, the Psalms are not the voice of God. A poem does not make you a person. A person makes you into a person. Two people, in fact. The image of a person being knit together is a lovely one, but that isn’t how procreation works. Outside of the Bible, there are no records of virgin births.

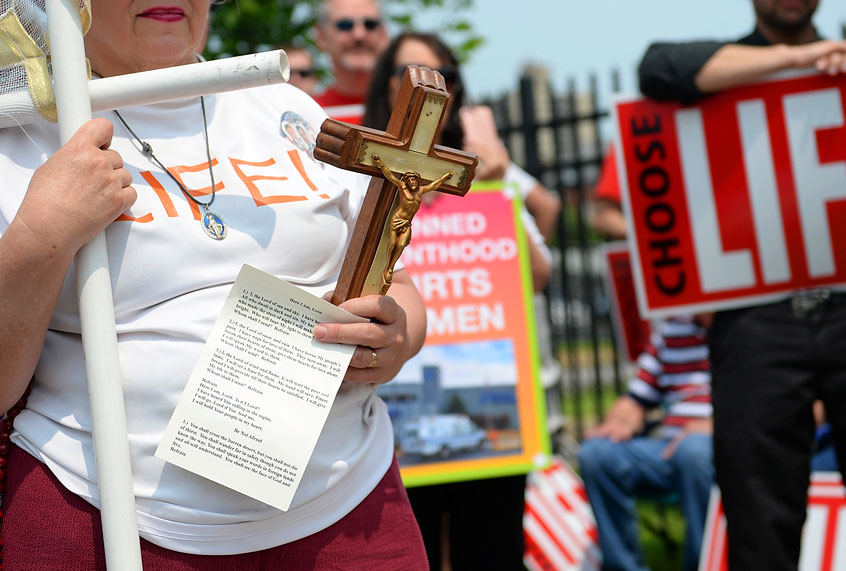

The Evangelical church believes there is currently a war on Christianity. And maybe they’re right. But they have the reasons all wrong. They think they are the ones defending life, when really, we are the ones defending our lives from them. Especially marginalized people.

Christian women: you can choose not to have an abortion. But if you believe in a God that would smite a woman who would not carry her rapist’s baby, then maybe you need to reconsider your God. Is that the kind of God that deserves worship? As I deconstructed my own faith, I decided it was not. Either way, your god is thankfully not the god of everyone. And no one’s god should have any influence on laws. Church and state are separate.

This means EVERY church.

This means EVERY state.

I have the same issue when people say ridiculous things like, “What if that kid was going to be the next President? The person who cures cancer?” or “Imagine if you chose to abort A (my kid)!” You can’t apply this kind of logic to human beings. A fetus cannot survive outside of a womb and a womb cannot exist without a mother, an already-formed, completely sentient human being. An egg also cannot become a fetus without sperm to fertilize it. A child cannot grow up to be an adult without the support of other adults for care and safety. A child cannot thrive in a society with such disregard for genuine human life. This is science, which is real, not hypothetical at all.

To believe in the sanctity of life is to treat every living person as if they are sacred and holy and have value. This is not reflected in our laws or even in our churches. If you say you are pro-life, then you must change your life: you must also be against war, against the death penalty, for universal healthcare, for access to birth control, for comprehensive sex education, for mental healthcare, for gun safety laws, for a living wage, for environmental initiatives, for the care and safety of refugees. This world you’ve created and continued to perpetuate in the name of your specific, myopic God, built out of cherry-picked verses from the Bible, words taken out of context, metaphor turned literal, a historical suggestion turned into law and carried out by men, dismissive and detrimental to the lives of women, is not a world anyone should bring a child into.

And yet we do.

Why?

Because a child is hope.

Sometimes. If the child is wanted. If the child is chosen. But a more immediate hope is a woman who can choose the trajectory of her life because she has autonomy over her body. Maybe she’ll be president, maybe she’ll save the planet, maybe she’ll find the cure for cancer, maybe she’ll save your life someday — or the life of your child. She is real. Neither hypothesis nor metaphor. She was brought up. She already loves and is loved. She is already sacred. She is already in the process of being. She has the ability to make choices. And we should let her. Not just let her, but let her without question and without shame. Because our world will become more kind, and hopeful, and even holy, if we do.