The New Right has disrupted political norms around the world. This dangerous and radical movement views multiracial cosmopolitan democracy as an existential threat. To that end the white power movement and other elements of the weaponized so-called “alt right” have used lethal violence and other acts of political terrorism against nonwhites, Muslims, Jews, journalists and other designated “enemies” in Europe, New Zealand and the United States.

The New Right has also captured ostensibly “democratic” governments through the use of “normal” politics. The most prominent example being Donald Trump and the Republican Party. The extremist turn of today’s Republican Party is so great that it has more in common with radical right-wing explicitly anti-immigrant and anti-Muslim political parties in Europe such as Alternative for Germany than it does mainstream centrist parties such as the Democrats in the United States or the Labor party in the United Kingdom.

With this power, the American New Right is imposing an agenda of racial authoritarianism and invigorated white supremacy which seeks to undermine and restrict the human and civil rights of non-whites, women, gays and lesbians, Muslims and other groups viewed as the enemy Other. In total, Trumpism is racial authoritarianism and malignant hostile sexism in the new service of neoliberal gangster capitalism and Christian right-wing theocracy.

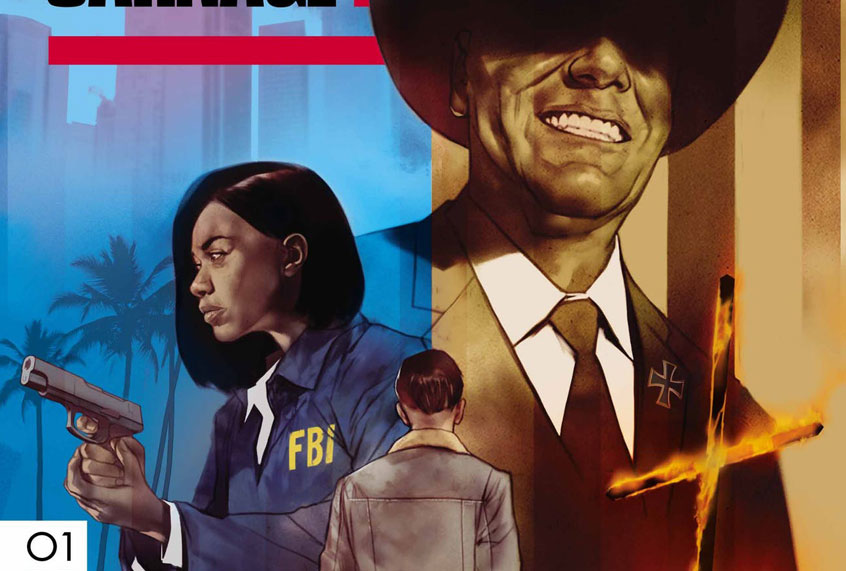

Bryan Edward Hill’s graphic novel “American Carnage” is a product of this global moment, but it is so much more. “American Carnage” is a noir detective story about a “biracial” black man and former FBI agent turned private eye who infiltrates a white supremacist organization with the goal of exposing its connections to a right-wing media personality and the recent murder of a law enforcement agent.

As Hill explained to the Washington Post, “American Carnage” is also an exploration of the main character’s identity and sense of place in the world: “It’s really me telling a story about a character who is struggling with his own sense of self and he’s kind of an outcast, because of the choices he’s made.”

In telling one character’s struggle about his “racial” identity, “American Carnage” offers a history lesson about how African-Americans have long infiltrated white supremacist organizations through racial “passing.” By pretending to be white and putting their lives in extreme peril African-Americans brought greater attention to the horrors of white mob violence such as lynchings and helped to bring down the country’s largest terrorist organization the Ku Klux Klan.

In addition to “American Carnage” Bryan Edward Hill is also the writer of the comic books and graphic novels “Batman and the Outsiders,” “Michael Cray,” “Detective Comics” and “Killmonger.”

In my recent conversation with Hill we discussed what he learned from his time with white supremacists and other members of the white power movement, how the internet and social media make it easy to radicalize angry and lost men and boys, and does a crisis in masculinity explain why they are attracted to both the New Right and groups such as Al-Qaeda and ISIS. Hill also shares his thoughts on how storytellers and other artists should approach the Age of Trump.

This conversation has been edited for clarity and length. You can hear our full conversation on my podcast, “The Chauncey DeVega Show.”

My conversation with Bryan Edward Hill can also be listened to through the player below.

The New Right is on the march. Nazis and other white supremacists are killing people and engaging in global terrorism. Donald Trump, the Republican Party and the so-called alt-right are channeling white right wing fake populism and white rage. “American Carnage” is truly of this moment but also something much more. What was the genesis for the graphic novel?

“American Carnage” was always a response to how these ideas are persistent and will likely be so for a long time. They just live in different spaces. There will always be people that want to radicalize others based on fear. This radicalization will take place in different ways and using new technology.

For example, YouTube is a kind of a free-for-all of radicalization. There are no limits on it. Young men — and it is almost always men — are looking for some kind of identity and agency in a world where they’re not finding it because this world exists to eat away at our self-esteem. These men are gravitating to extreme ideas just so they can get back to zero. They’re starting with a deficit of self-esteem. This means that they will listen to someone who tells them how to convert their fear into anger and where to point that anger. These young men listen because it feels like power. That’s what is so insidious about it, the radicalization, this seduction into anger.

In Issue 6 of “American Carnage” that is why I have the character Wynn Morgan speak in a way that is strangely compelling while also being equally horrifying.

People have asked me, “Bryan, how did you do that? How did you write that? Man, that was so chilling.” What I wrote was just the subtext of any two hours of Fox News. And all I did was take their subtext and made it obvious. I have a background in marketing and advertising. I understand how people are manipulated. Throwing a direct flashlight on how people are so malleable, and this radicalization and anger was my intention in “American Carnage.” I wanted to create a narrative and a world where no one really gets away unscathed, reader included.

Are we in a moment where there is a global crisis in masculinity? Is this why so many young men are swept up by radical movements such as ISIS and the New Right?

I wouldn’t say that there is a crisis of masculinity. Most generations have been able to focus their animus on a specific enemy. They knew the name of the dragon. In the 1940s we have the Nazis, the Axis Powers. That was the dragon. Soon afterwards, it was the combination of death by atomic weapons and the Soviet Union. So especially in America, and the West more generally, we’ve defined ourselves in opposition to an agreed upon enemy.

Because we don’t have an agreed upon enemy at present too many people have turned other people into their enemies. Terrorism is difficult because it rarely has a centralized figure that you can hang the lantern on. It doesn’t have the same form and structure of a formal government power, a nation state. Terrorism can happen at any time without reason so it maintains the culture of fear.

In the West, we don’t really handle those amorphous fears very well because philosophically, we don’t engage with fear enough. We tend to pretend fear is not there and that somehow remedies it. And we also just get angry and act from that emotion. Now, we’ve just turn each other into the enemy

Social media is part of the problem as well. It does not help to create a healthy and mature type of masculinity because there’s always someone who’s waiting for us to just have a knee-jerk reaction and these voices online support whatever aggression can serve their own interests. People are not being forced to have to grow and to deal with the vicissitudes of life on their own.

How did you channel discomfort in “American Carnage”?

If I’m going to come at somebody, I’m coming at them from the front. You’re not going to read “Batman and the Outsiders” and then suddenly turn a page and there will be political issues being discussed in a soapbox type way. I don’t do that. When I engage, I engage you from the front. That’s why the book is called “American Carnage,” so the reader knows what my approach and themes are immediately. That is why the imagery in “American Carnage” is so stark from the very beginning.

I’m making a pact with the readers. You can’t complain to me about the experience within that book because at no point did I lie to you about, by analogy, how the meal’s going to taste.

With “American Carnage” I wanted to engage difficult issues. I also wanted to put a measure of personal risk into the book. That energy and those themes come from me. None of what I summon in “American Carnage” are quotes from other people that I’m just placing inside of a work. I have to generate all of those feelings and emotions. I am an artist and I am willing to pay the personal emotional price to be able to express those sentiments and ideas.

I tell people — and they may not believe me — but I don’t think that “American Carnage” is a book about politics. I think it’s a book about ethics. Politics is just the expression of ethics. And ethics are really what we as a country need to be discussing right now with Donald Trump and all that is happening.

Is it ethical to put children in cages? Let’s forget the political issue here. Let’s forget voting and demographics etc. etc. Let’s just talk about “Are we saying as a nation that it’s ethical to put a child in a cage because their parent may have committed a crime?” Those are the questions I think we have to ask. Is it ethical for people to have full-time jobs, and, in theory, health insurance, and then when they get sick, they can’t afford health care — is that ethical? Is it ethical to make profit off of peoples’ physical illnesses? These are the questions that we should be asking.

Many of those men and some women who are attracted to radical, fundamentalist and other extreme belief systems are very immature in terms of their understanding of the world. They are also stunted in terms of their emotional intelligence and political sophistication. Those types of extreme ideologies and politics give lost souls family, home, community, a renewed feeling of “masculinity”, in-group prestige — and for some of them money and other material resources. Did that inform “American Carnage”?

My art is about empathizing without judgment. Not sympathizing, but rather empathizing — this distinction is very important. So when I met with people in the white hate movement, they thought I was looking for an argument. To them, I was likely some lefty black person who was going to set them up. I get it. I understand. But unless you’re dealing with an actual psychopath or sociopath, it’s virtually impossible for a human being to not connect on some level if the person is being patient and genuine. When I’m talking to one of these people I am not worried about their Nazi “14 words” slogan. Fine. Everyone has their little dog whistle. We all got words.

But what I do recognize in these conversations with these members of the white right is how when you’re lost and you’re scared and you don’t see how you’re going to succeed in the world because you believe that success requires having something that you don’t have. And you think that I have an advantage over you because of the color of my skin and that bothers you, you envy that. And you’re hungry. Your friends are hungry. And you feel like you’re being told that you have privilege but you can’t feel the privilege because privilege generally is something that can’t be felt. Most people don’t get up in the morning and walk out of bed to their bathroom thinking about the privilege of not having to use a wheelchair. Life is just what it is for those who can walk. It’s hard to emotionally recognize what’s being told to you because your belly hurts, because your brother came back from the Middle East and he’s on Fentanyl now because he couldn’t afford heroin. And that’s just pain.

Someone comes in and says to these angry white men that, “Well, the reason why you hurt is because of them, because they get everything and they waste it. What do you get? You get nothing.” And then you’re told you’re the problem. That’s a very seductive argument. Far more seductive than, “Yeah, the world is kind of pitted against all of us and we’re going to have to work together and figure out a way through it.” No. It’s much easier to be like, “It’s their fault.” And then as took place with Nazi Germany a charismatic madman comes in and says, “You know why you hurt? Because of them.”

Trumpism and this global breakdown in democracy are going to produce a great amount of bad writing. Work that is too topical and obvious. How did you avoid those pitfalls in “American Carnage”?

Don’t try to create anything to specifically injure anybody. There’s no vengeance in my work. I offer engagement. It’s thoughtful engagement and I do not write from a place of wanting to get revenge on anyone or any group. Those principles keep my work from being petty. Some have read “American Carnage” and asked me, “Is Wynn Morgan really Donald Trump? Is Jennifer Morgan supposed to be Ivanka Trump?” My answer is “No!” Why? I don’t think the Trumps are that interesting. I certainly don’t think they’re interesting enough to make the center of a story. The Trumps are just too simple to put into a story. You might see some allegories because the characters in “American Carnage” and the Trumps do some of the same things — but remember these are things that Richard III did too. These are things that Lucifer did in the Garden of Eden. Their bad behavior is very old.

I don’t care about the Trumps that much. One day, this man shall not be president. Now, I don’t know when this day will be, but one day he won’t. The moment that I can legitimately never think about Donald Trump I’m not going to do so.

Ultimately, I am going to present the story to the reader and I’m going to be as honest as I can be while doing so. And I know it’s honest because it hurts to do. And I’m going to do that. You’re going to feel about my work however you choose to. I am not going to tell you how to feel. That is not my job.

You have been vocal about this on Twitter and elsewhere. How are readers imposing their own politics on to “American Carnage” and your other work?

People are always going to project their own issues on to writing, art, literature, music what have you. That is human nature. I don’t mind it. If that’s the experience they had, then so be it.

So much of what we consume in popular culture is sanitized and designed to not have any impact whatsoever. It is literally designed to be a pleasant way for people to waste time because there won’t be any blowback and there is less economic risk. Therefore, anything that makes a person feel a certain way that they did not like, did not want to feel in that moment, makes them feel injured in some way.

Their response is then, “What right do you have to injure me!” Maybe a writer or other artists said something that a person thought was interesting and then they follow that other person on Twitter. Then that person they were curious about or whose work they liked said something that was bothersome, that irked them, upset them. Now what really happened is they were made to feel something they didn’t want to feel. And now that this person feels violated it becomes, “You did something to me which means you must have had had ill intent. There’s no way you did that in an objective way. There’s no way you just did that without wanting to make me feel this way. You wanted to make me feel this way. You hurt me. You made a sequel to a movie that I love and you did things that made me feel things I didn’t want to feel, so you must’ve really wanted to punish us, the fans!”

The logic is, if I can make you a monster, I can make you bad person, if I can ascribe ill-intent to your action, now I’m justified in doing ugly things to you because I want to make you feel what you made me feel. For example, “Rian Johnson hurt me so I need to hurt him. And clearly, he must have wanted to hurt me because look at him. Just look at him!”

I love the original “Star Wars” films and most of George Lucas’s vision. He is a genius who gave the world a very special gift. But I can’t stand “The Last Jedi.” What the new “Star Wars” sequels have done to that film universe is horrible. With that having been said, I do not like “The Last Jedi” but I didn’t take the movie personally. My childhood isn’t “dead” as the saying goes. Rian Johnson didn’t kill it. J.J. Abrams didn’t kill it.

I’m not a huge fan of “Last Jedi” either. That’s not the point. I know that Rian Johnson did not make that movie with the intent of bothering me. He made choices. People make choices. He’s an artist. I look forward to his next films. I will always watch one of his films. He’s a very solid filmmaker. I didn’t respond to “Last Jedi.” Johnson did not make that movie to hurt me. He wanted me to like it.

What of those people who are so deeply invested in popular culture that it becomes a part of their self-esteem and identity? I am thinking specifically about these very heated debates about “representation” and “diversity.” For example, when I see folks online and elsewhere who say things such as “This movie hurt me” or “I feel so validated. There were people like me in the film, TV show, comic book or video game” such sentiments do not usually register with me.

I’m 42. So I grew up with a different relationship to entertainment and art too. Again, I empathize. I get it. It feels nice to see yourself in something that you love. I can’t step on that feeling for people. At the same time, I would be very careful where one places their self-esteem. I wouldn’t hand that much power to a movie or a comic book or a song or a television show or what have you.

Also, I think a lot of these reactions are because we live in an era where most people feel powerless. Thus, anything that can make you ignore that feeling is compelling. And if a person feels like, “Well, if I complain about this film or TV show or comic book, if I make some noise about this, then I can feel powerful because I can harness that because there’s thousands of me and we can all go online and we can use social media. We can do something.” I kind of get that as well. I don’t judge people for the feeling. I understand it. I don’t often share their feeling. My brain does not usually work that way.

The only thing that I get a little concerned about is if a character is not allowed to do certain things because if said things happen then they are somehow besmirching everyone who looks like that character or everyone who’s that gender or that race or some other identity. This expectation is preventing characters from being able to have freedom of action and movement in storytelling. I don’t see how ultimately that is going to help us. If a black character has to always be perfect in a narrative, then there are not that many functions for that black character in the story. If a female character is not allowed to ever lose then she can’t ever be Indiana Jones. She can’t ever be one of those icons because part of that comes from watching them lose and then figuring out how to turn that defeat into a win.

I love everyone who spends their money and time on my work. But if you notice, I don’t try to put a fence around my audience or my characters. I don’t make that part of the Bryan Edward Hill experience. I guess I could. I’m a black writer. I could do that. I do not want to get into the competition of who can be more offended by a thing. Instead, if I don’t agree with something that I see, maybe I’ll create something in response. I might not tell you I created this work in response to something I found problematic because you, the reader, the public, do not need to know that.

So if I’m personally concerned with the way how, for instance, black males are presented in society and entertainment, I might address that in “Batman and the Outsiders.” I tend to respond with my work. I throw work at the problem. But I’m an artist and that’s kind of how I think. So instead of getting upset about a given issue and telling everyone that I’m upset about it, I’ll just make something different.