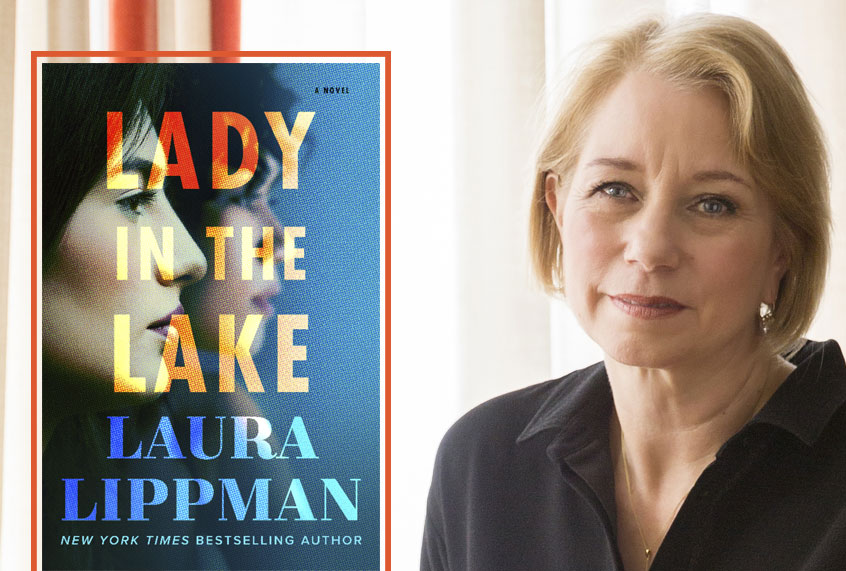

In the author’s note for her new book, acclaimed veteran crime novelist and New York Times bestselling author Laura Lippman admits she didn’t set out to write a newspaper story when she began her beguiling new novel “Lady in the Lake,” which borrows from two real deaths in her hometown of Baltimore. But where else would a woman like Maddie Schwartz find the cover she needed in 1960s Baltimore to pursue the stories she feels suddenly called to tell?

A scoop on that murder for a local newspaper — rewritten by a male reporter, of course — opens the door to a crappy job assisting the helpline columnist, which Maddie uses to look for more opportunities to snag a byline and prove herself. A help column query leads to Maddie finding herself in the middle of another mystery: how the body of Cleo Sherwood, a young single mother, ended up in a city park fountain — a story that, because Cleo is a black woman, warrants not even a fraction of the reporting attention from her colleagues that Tessie Fine’s murder did.

Yet again, Maddie will not be deterred, and launches her own investigation into Cleo’s murder. As determined as she is, though, there’s a lot she doesn’t know about the worlds she’s thrust herself into. Lippman follows each of Maddie’s point-of-view chapters with one in the voice of a minor character she’s just encountered, deepening the narrative for the reader while allowing Maddie to make realizations and connections in her own time.

One voice, however, runs through the book, and rightly so: It’s Cleo who opens the book, and Lippman weaves her beyond-the-grave narrative throughout the slow-burning story, reminding us that though Maddie might be fighting to solve the mystery of Cleo, the story of this body, this death, doesn’t belong to the upstart reporter but to Cleo herself. “Alive, I was Cleo Sherwood,” she tells us. “Dead, I became the Lady in the Lake, a nasty broken thing, dragged from the fountain after steeping there for months . . . and nobody cared until you came along, gave me that stupid nickname, began rattling doorknobs and pestering people, going places you weren’t supposed to go.”

Lippman didn’t set out to write a newspaper novel, but “Lady in the Lake” is certainly a triumph of the genre, a lively and unsentimental immersion into an atmosphere that’s largely gone now, for better and for worse. This is Lippman’s twelfth novel outside of her popular long-running Tess Monaghan series, which launched her career as a novelist in 1997 after two decades of newspaper work. Fans of her nonfiction — such as her recent personal essays in Longreads, “Game of Crones” and “Whole 60,” which take a candid look at women and aging — will have something new to look forward to soon: Lippman’s new five-book deal will include a book of personal essays.

On a recent phone call, Lippman and I discussed the world of newspapers that no longer exists, the influence her late father had on this book, women and men and crime fiction, and the two true crimes that inspired this novel.

Our conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Maddie Schwartz reminds me of true crime podcasters in a way. If she were in 2019 pursuing the obsessions that she pursues, she might have her own podcast instead of pursuing a career at a newspaper. She joins a search party, and she’s hooked on this thrill of helping find the body of this missing girl, and then decides to start pursuing leads.

Were you consciously hooking into the true crime storytelling boom that’s happening right now that happens to feature so many women?

No. I think that’s a great insight, though, and I think perhaps subconsciously that was there for me because I do listen to true crime podcasts. But I’ve found myself in a smaller sub-niche of the audience for true crime podcasts in that I was part of a group of women, a lot of whom are crime lovers, who always liked true crime, and we liked it when it was unfashionable and tacky.

In January of 2014, I was invited to do a panel at the Key West Literary Seminar, and the other panelists were my friend Megan Abbott and Gillian Flynn, whom I know as well, although I don’t know her as well as Megan. Having invited us, [the organizers] then said, “Well, what do you want to talk about?” It’s probably not fair, but I inferred that the Key West Literary Seminar actually had no idea what to do with a weekend full of crime writers.

And Megan and Gillian and I, who had bonded over our love of true crime . . . Gillian in fact, when I blurbed “Gone Girl” — and now it’s kind of hilarious, it’s like once upon a time, I blurbed this third novel by the up-and-comer Gillian Flynn — she had, as a gift, sent me a copy of the book, “Until the Twelfth of Never,” and it’s the book that inspired the two miniseries based on the Betty Broderick story out of Southern California. Betty Broderick killed her ex-husband and his new wife and then tried to claim — I don’t know exactly what you would call it, the discarded wife defense? As in, she was just emblematic of all first wives everywhere who did everything for their husbands and then got dumped for a trophy wife. That defense was ultimately not successful for her. The book is fascinating because both of these people in this marriage are so toxic and so horrible. You’re not rooting for anybody. It’s an outstanding book by Bella Stumbo.

So we decided at this Key West Literary Festival to talk about how we loved what most people call “Lifetime movies.” People use it as a pejorative. And that we were drawn to these movies because there was a time when, if you were looking for women in the central roles in crime stories, these based-on-true-story TV movies, some of which were made for Lifetime — many more of which were made for major networks, which people have forgotten — that’s where you went to find women as the driving forces in story.

When the true crime podcast boom began, I saw myself as the natural audience, and then I found myself interested, but not as enamored as most people. Because first of all, it just wasn’t that new to me. It was like, gosh. I mean, where have you been? Have you heard about some of these books by a guy named Joseph Wambaugh? There’s so much good stuff out there already.

But one of the things that did interest me, and you saw it popping up in pop culture right away, it was actually part of the plot when MTV remade “Scream” . . . and one of the characters is actually a podcaster. This was really early on. And I’ve just finished my friend Alison Gaylin’s book “Never Look Back,” which is fantastic — and Alison is definitely in that group of friends who also always loved true crime, she can talk a lot about how much the book on the Manson murders affected her as a young kid growing up in California — and she writes about a podcaster. And Elizabeth Little, another young crime writer I really like, she’s got a book coming out, I think in 2020, that involves a podcast as sort of a secondary storytelling thing. So, it’s out there. It’s sort of in the air, in the water, and we’re all taking it in.

But I think I come to it with a little bit of skepticism because the podcaster, even though the podcast is often a professional, a lot of these true crime podcasts are really about the reporter. And at the end of “Lady in the Lake,” Maddie has the realization that whoever she’s writing about, she’s always been writing about herself. So, I think that was all in there, and it’s a great question but I never put all those connections together until just this moment.

As a novelist, are you always in some way writing about yourself?

Yes.

In what way?

I’m everybody in my novel. I can’t not be, no matter how different they are. No matter how much distance and perspective and sometimes flat out distaste I might have, I have to conceive on some level these are all my progeny, every single character I create. But Maddie, probably more than most characters I’ve created, is definitely an iteration of me. In some ways, Maddie allowed me to work out my own feelings about the fact that when I use real crimes for inspiration, as I often do, as I did in this book, am I not appropriating somebody’s story? Am I not using somebody else? And is that right? Is it wrong? Is there a right way to do it that makes it better?

I think of [Maddie] as a heat-seeking missile, and she just burns her way through this story, her life. And for all of her desire and ambition to become a reporter, it turns out that there’s this city around her that’s teeming with stories that she doesn’t even glimpse, even though they’re right there. There are people in the same room with her, there are people who talk to her, and she doesn’t even think to be curious about them because she’s only thinking about the story that she’s deemed important. I’m worried about all of those things. I’d say the main different between Maddie and me is I don’t think she’s worried about it.

Maddie is an unruly woman for her time, right? She walks away from her respectable marriage. She has an affair with a Black police officer. She’s relentless in pursuing this job that she wants that doesn’t want her. But what I found compelling was that she’s also unapologetically a woman of her time and of her class in that she is deliberately leveraging her looks, her flirting and social skills, to work the men around her in order to get what she wants. In that way she reminded me of my grandmother, but she’s also every woman now that I know who has ever had to prove herself in hard news, in defying the expectations that are put on her.

When you’re creating a character like that, how do you work out the balance between the period authenticity of a character like Maddie but also writing a heroine that today’s readers, even young women, are also going to be able to see themselves in?

I’ve learned a writing lesson recently from writing personal essays. It’s something I never intended to do and something I didn’t think would inform my fiction that much. I thought the fiction would inform the essays more than the other way around. But I’m beginning to find, and I guess I always knew this on some level, that the more specific you are, the more universal it feels. That if you just are OK with creating a very specific character in a specific time and a specific place with a specific background, somehow those characters will feel more real and more relatable than these generic characters.

I recently went on a binge of rewatching all of Christopher Guest’s films. He makes that one called “For Your Consideration” where they take this movie about Purim and they try to make it super generic because they don’t think anyone would come see a movie about Southern Jews. That’s just too weird. And I think by the time at the end it’s like they’ve turned it into Thanksgiving because no one would ever understand what was going on otherwise.

I think that’s the mistake that some people might make, which is, “Oh, I have to keep things very general, very expected. How can anyone relate to my characters if they’re not like they are?” And I’ve never worried about that, for better or worse. I’m not saying I never worried about it because I’m some incredible visionary who saw how it would work, I just couldn’t do it. I’ve always written extremely specific characters, some of whom aren’t that likable. I feel like I was writing unlikeable characters before people started talking about the whole problem with unlikeable characters. I don’t even buy it. When I teach writing, I tell my students, “If someone turns your work down and their reason, they say, is because the character’s unlikeable, that’s like someone telling you they can’t go out on a date because they have to wash their hair that night. They’re trying to let you down easy.”

Likable has never been the issue. The issue is: Is your character interesting? Do people want to spend time with that person?

I’m a big Howard Stern fan — which strikes some people as odd — and there’s that wonderful moment in “Private Parts” when they walk in the market research on him. The first part is a huge number of people say they can’t stand him, they hate him, they don’t know what he’s doing on the radio. Then, a huge number of people say that they keep listening because they don’t know what he’s going to say next.

In creating a novel, part of it is all you want to do is create people that people can’t stop thinking about and they can’t wait to see what that person’s going to do next. Maybe precisely because it’s not what they’re going to do. Most of us don’t simply decide after meeting a guy we knew in high school that, you know what? My marriage isn’t enough for me. I didn’t do what I wanted to do. I’m out of here. I’m going out there for something of my own.

Most of us probably don’t think, you know what? I’m going to go join the search party for the missing 11-year-old girl because that just seems like an interesting thing to do, and then doesn’t leverage that to say, this has news value. Well, if my story has news value, then it’s my story and I want to write it.

I didn’t start out to write a newspaper novel. No one was more shocked than I was. It was like, oh, of course this is what Maddie would do. I set out to try to figure out a story in which these two deaths — that were based on real-life deaths in 1969 — what could possibly link them? And I realized it would have to be someone like Maddie who, seeing how much attention this gave to the death of an 11-year-old white girl, would sense an opportunity in the death of a 20-something African American woman who isn’t of that much interest to the city at large.

The bottom line is, Maddie’s not going to be allowed to pursue a hot story. There are always reporters there ready in place to go after the story that everybody’s interested in. She sees early on that her best bet is to take a story that people aren’t particularly interested in and make that a story that she can find what’s fascinating about it.

The discrepancy in how those two disappearances were treated — it’s slightly better today, but not really much, in the differences between how the disappearance of a white girl like Tessie Fine versus a black woman like Cleo Sherwood are treated.

Could you talk a bit about the two true crimes that inspired the story, and then talk about how you built the character of Cleo? Through her haunting — of sorts — of Maddie throughout this story, she establishes herself as not just a voiceless missing or dead girl, but as a real living and breathing character throughout the story as well.

In 1969, when I was 10 years old, an 11-year-old girl named Esther Lee Lewis disappeared, and within a few days her body was found. She’d been murdered, and the case was solved very quickly. Important to note that although I drew a lot of facts from the real-life case, anything about the solution that’s offered in my book is completely manufactured. But in real life, an 11-year-old girl was murdered by a man who worked in a tropical fish store, and there was this almost CSI development, which is when they found her body, it was the presence of this non-indigenous sand that helped them find her killer.

It happened very quickly. In terms of the why and what happened, it was almost matter-of-fact. He claimed that he snapped, and he remains in prison to this day, to the best of my knowledge.

There I am, 10 years old, reading the afternoon newspaper, and obviously I’m obsessed. I didn’t know kids could be murdered. When you watched television in the late 1960s, these were not the stories that you saw, and it made a huge impression on me.

Jump ahead 20-something years, I’d come to work at the Baltimore Sun, and I had never heard of the real-life death of Shirley Partridge, whose body was found in the fountain of Druid Hill Park. There was a rewrite guy named David Micheal Ettlin, he would talk about this. He gave a tour of Baltimore to reporters who were new to the city. Every now and then it would pop up in a column that was written by one of my colleagues about just interesting historical stories from Baltimore. Here was the death. It was never even classified officially as a homicide. No one knows how she got there. No one knows what happened.

Someone who comes to our [Fourth of July party] every year is a man who goes way back with my husband, named Scoochie. Scoochie told me that he knew Shirley Partridge when he was a kid. He was friends with her son, and he has this memory of zipping up her dress when she was getting ready to go out one time. Writers are awful about writing. Immediately, I stole that and I gave it to the character of Little Man, Cleo’s son.

But here’s this one story that I’ve known my whole life, and here is another story that, if I hadn’t come to work at the newspaper, I might never have noticed. And I’m very struck by that, and it isn’t that different now.

I have a friend named Katelyn Burns who did a piece in Politico this week. Katelyn was the first trans woman in the Capitol Hill press corps, and she wrote about trans issues in the democratic debate and how Julian Castro was well-intentioned but kind of got the words all wrong. And one of the things that she wrote just sent a cold breeze through me, which was she said, “As many trans women of color would have died under the Hillary Clinton administration as under this one,” and it was just like, wow. Yeah, it’s right. She was writing about who are the candidates speaking to when they think about trans issues? They’re not really worried about the votes of the people who are trans because that’s not a big enough part of the demographic to win an election. They’re trying to appeal to so-called progressives who think they’re woke on trans issues.

There has been some progress made, but the fact of the matter is is that women of color still disappear in a way that is not fetishized by network news and now social media. And it just doesn’t seem to change that much. I’m trying very hard. I don’t have a perfect memory and I’m not as immersed in news as I used to be, but I can think of two or three stories involving the deaths of young white women in the past year that have gotten a lot of attention, and I can’t think of a death of a woman of color that’s become a national story in the same way.

Literature and culture can or has the potential to drive change as much as it can reflect change. What is your sense within the genre of the archetype of the “dead girl” being the beautiful young white body that becomes this object of fetishization — is that changing throughout the genre?

What’s been really fun is to watch female writers decide that at least they’re going to be the ones who tell the stories. I’m well on record as saying if you want to know the prize-winning formula for detective fiction, and I’ve done it so I’m not exempting myself from this, but if you start looking at the books that win prizes, the books that are taken seriously, and they can be very good books. They often are very good books. Some of them have been written by very good friends of mine, and as I said, I’ve written my own. But it comes down to a beautiful woman dies and a man feels bad about it, and that is an incredibly handy description of a lot of the best-known crime fiction of our time.

Women are by and large the audience for crime fiction. They’re like 80%, 90%, and as women start to fuse these stories and tell their stories themselves, I’ve noticed that some male writers are increasingly disgruntled about it. You see these complaints about, “Oh, I’ve been told that I have to write under initials so that I appear to be female—”

I’ve seen men doing it. Most famously, A. J. Finn, which is the pseudonym for Dan Mallory. Although, it was really well known that a man was writing that book. There’s some others. I don’t feel that there is any directive that men have to write as women in order to get published. I don’t think there’s any directive that you have to have an unreliable female narrator to be successful right now. I don’t think there’s any directive that you have to have a noun in your title that refers to a woman, whether it’s wife, girl, sister.

“Lady.”

Lady, widow. I don’t think any of that is true. I think what’s changed is that I think crime fiction has had a really great qualitative upgrade and that some writers who were doing perfectly fine B-plus work are now shocked to find out that that doesn’t necessarily earn them a place at the table. I’m sure in their heads they’re doing A-plus work, but I’m seeing this disgruntlement among people that I consider . . . They’re good. They’re fine.

They’re doing perfectly good. But to me, when I see these complaints about, “I can’t get published and it’s because I’m not a woman,” it’s like, give me a break. Come on. It takes me back to being in newsrooms in the ’80s and ’90s when I had colleagues, good guys, but they would actually say things like, “I’m going to start a white men in journalism club,” as if they were somehow at a disadvantage for being a white man in that world. It’s just crazy the way people can perceive themselves as having been short-changed when they’ve been occupying an enormous side of privilege for a long time.

You’re trying to tell people that white male is not the default, that the book doesn’t have to be about that, and the statistics actually on writers of color and characters of color in crime fiction are still quite depressing. There’s a woman named Frankie Bailey who has a comprehensive list, and the first time I heard the stats from this list, I thought no. No, that can’t be possibly right. And I started naming names, thinking is so-and-so on Frankie’s list? Yes. Is so-and-so on Frankie’s list? Yes.

But what’s been great is that we are seeing some new good voices being championed, and I’m excited for that. My experience is that change happens, and then every time there’s progress there’s also regress.

I tell this story, and it makes the person in the story very angry. But I started out writing private eye fiction. I belonged to the Private Eye Writers of America. In 1999, it had its second in what, to this day, is its most recent convention, and they put together a panel about the private eye in the new century. It was five white men, and there was pushback. There was an uproar, and the defense was, “We didn’t put the panel together. This is what booksellers told us they saw as the future of the PWA. Blah blah blah.”

At one moment, there’s this one unguarded moment, when the man who was organizing the convention wrote, “Women have had their turn.”

I was like, OK, wait a minute. First of all, women saved the genre. Sara Paretsky, Sue Grafton, and Marcia Muller took a moribund form that was basically existing on the fumes of Robert Parker and the Spenser TV show and they made it viable again. And I have never gotten over that idea, because you realize that that’s always there bubbling beneath the surface, which is everybody else is getting a turn. It’s like they’re being polite: “OK, you can have the toy for 15 minutes . . . . but don’t forget who it belongs to.”

Right.

“And that we’re only sharing because we’re nice people.”

I see a lot of white men thriving in crime fiction, so I’m not worried about them at all.

It made me think about the male characters, especially at the newspaper, in your novel. How probably a lot of them would end up on the Shitty Media Men list today, right? They’re not romanticized in this book. But the book also, to me, read a bit like a love letter to that era of the business, a way of doing journalism that no longer exists.

Oh yeah. That’s not even my era. That was my dad’s era.

I had one terrific advantage that very few people my age can even say they had, which is in 20 years in journalism from 1981 through 2001, I worked in three cities, and in two of those cities I worked in out-and-out competitive situations.

In San Antonio, there were three newspapers when I got there. There was the San Antonio Light, and then Murdoch had the Morning Express and the Afternoon News. Then, in Baltimore when I got there, the Evening Sun and the Morning Sun might have been owned by the same people, but there were two different staff, and we competed against each other and it was glorious.

The Evening Sun, in particular, was kind of a throwback. And then writing about the Star, this raucous afternoon paper down on the waterfront, to a certain extent it had the spirit of the Evening Sun in there. Even at the Evening Sun into the early ’90s, we played practical jokes on one another. We would eat wings after we made deadline. I remember one time they got a Ouija board, and I was the most recent hire. They made me sit opposite the Ouija board with our most senior hire, a man named Carl Shatler. Carl had started at the Baltimore Sun the year I was born and was still one of its most valued, respected reporters. We claimed to call up the ghost of H. L. Mencken, who was an Evening Sun writer, and ask him how long would the Evening Sun last?

I knew all of that, through experience but also through war. My dad came to Baltimore in 1965, and I visited the newsroom for much of my childhood and had a certain sense of it.

Also, I read a lot of Nora Ephron, and I don’t know if people remember her book about journalism called “Scribble Scribble”? But she had a piece about the New York Post in the early ’60s that really informed a lot of my ideas about what newspaper life would have been for Maddie Schwartz in the early ’60s.

These days, right, you’re more likely to read about a heroine who’s running a podcast or working at a digital news site. So it’s kind of fun to go back in time. Like the rewrite guy, and the copydesk, and all of these things.

And it’s loud. I don’t think people have any idea how loud newsrooms were when everybody was on their typewriter, when no one had a direct line because everything went through a switchboard and then was forwarded to the phone on your desk and you could make calls out but no one could call into you directly. There were the wire machines, the AP machine and the UPI machine, which would ring. We’d actually have alarms go off if there was a big story happening. I remember those things. They were loud, and they were smokey, and they were dirty.

It’s dramatic. It was exciting to see “The Post” and “Spotlight” win awards and get attention, but it’s been my experience that movies about journalism can come off as super boring to anyone who’s not in the actual profession, because it’s hard to make somebody sitting there and thinking look interesting.

It’s a real danger, actually. I didn’t set out to write a newspaper novel, in part because I’m too aware of the dangers of the newspaper novel. It can be overly detailed and arcane. It can be too romantic. It’s a subculture that might not be as interesting as a lot of journalists believe. But I remember when “Spotlight” came out, we had it on a screener because my husband belongs to the Writers Guild or one of the award bodies.

I was down to the last five minutes, and my daughter, who would’ve been six years old at the time? That’s the most she would have been. She wandered in and she saw me watching the last five minutes of the movie when the presses are rolling, and the story’s finally going, and they’re telling you what happened. And she said, “What is this?”

I said, “It’s a movie about a newspaper,” and she said, “You mean like the place where you and Daddy worked?”

I said yes, and she said, “Can I ever work in a place like this?” And I said no and I burst into tears.

I’m usually not sentimental. I loved being a reporter, it was fun, but I always wanted to be a novelist.

So, I’m much less sentimental about newspapers than most of the people I know, but “Spotlight” really hit me hard. I think in part was because it was really pretty true to how newspapers report stories. It was so exciting that there wasn’t a love story in it. You have Rachel McAdams in a movie and she’s not in a relationship with any of her coworkers.

When you were talking earlier about how all of the characters are somewhat you as well, one thing that I appreciated about the structure of the book is the technique of how after the end of a chapter through Maddie’s point of view, we instantly switch to the point of view of the person that she’s just interacted with. Maddie’s not an unreliable narrator, right? But there’s just a lot that she doesn’t know.

There’s a lot she doesn’t know. There’s a lot she couldn’t know. How are you ever going to know the life story of the guy who tried to grope your leg at a movie theater?

The hand-off method, I thought, had the effect of propelling you through the book but in a different way than I feel like I usually see. It’s like the literary equivalent of a TV binge watching structure. But I think a lot of times when we talk about page-turner, we don’t really talk about the craft behind that, so I was wondering if you could share a little bit behind the process behind how you decided to structure the novel in this particular way.

Part of it was that I realized that Maddie’s story is triggered by a relatively minor character in her life. She’s not going to go back and have any sort of friendship or relationship with Wally [the high school boyfriend], and yet he initiated this huge change in her life. That created the rhythm, and I said, OK, so look for the opportunity in every chapter for — and it’s always a minor character. You only hear from the minor characters in that book. You don’t hear from Ferdie [Maddie’s lover, the cop, who plays a significant role in the story].

But it’s to see how these minor characters or these people that we think of as minor characters, they’re the lead characters in their life stories. Things are happening to them. They’ve had a different perspective, and I thought it was valuable in that it underscored Maddie’s incuriosity about everything except the things that she has deemed important.

When I was a reporter, my two closest friends on the Features section of the Baltimore Sun were a woman named Lisa Pollak, who was 27 or 28 when she won a Pulitzer prize for feature writing, she was that good. The other member of our group, and we were very like-minded, was a guy named Rob Hiaasen, and we were committed to the idea that stories about ordinary people were more fun to tell and more important to tell.

[Hiaasen was one of the five journalists murdered at the Annapolis Capital Gazette in 2018, to whom Lippman dedicates “Lady in the Lake.”]

I’d be sitting there, and the boss would come over to me and say, “This new TV show got a really big rating last night. It’s called Survivor. Can you write about that?” I’d be like, “I don’t want to write about that.” They’re like, “Forty million people watched,” or whatever it was. I’m thinking, that’s really still not a lot of people.

I wrote stories about shopping for a prom dress. The best piece I ever wrote in my 20 years as a journalist, and this is not just me. Most of the people I know agree with my assessment of this. In June of 2001, I wrote about the last day of school by telling the story through one 10-year-old boy’s eyes. Because everybody has a last day of school. Everybody shops for a prom dress.

Lisa wrote about a girl who wanted to win a contest for building a tower of Oreos. One day, I remember, we were sitting around, and in summer there were always these incredibly doldrums. We sat around in the summer of 2000, Lisa, Rob, and I, and we came up with this scheme that a lot of people hated. They were so negative about it, and we got some real criticism. I didn’t care. I thought we were brilliant. We came up with this series called Greetings From Baltimore, and we just decided to go to other places called Baltimore and write a story about whatever we found there.

Lisa went to Baltimore, Georgia, where she found people who actually ran a business selling clay to people who wanted to eat clay, which tapped into a lot of strange old Southern tropes. Rob went to Baltimore Street in Las Vegas and wrote about who was on Baltimore Street in Las Vegas. I went to the Baltimore Hotel in Los Angeles, which was a flop house.

That was always who I was as a reporter. I was the person who believed you should be able to open up a phone book, drop your pen, there’s a name, can you do it? There are other people who think that’s a completely ridiculous way to be, and they’re like, “Not everybody has a story, and not everybody is interesting.” I’m like, I don’t know. Isn’t it our job to see if we can make everybody interesting? If we can make these very routine rites of passage feel meaningful to other people? To me, that was always so much more interesting than writing about a movie star or a presidential candidate.

I was constantly being dragged into covering politics because I did it strangely well even though I hated it. It was my dad’s thing. It was almost this weird DNA thing. I hated writing about politics, but when they made me do it, I wasn’t bad at it. But I never liked it, and I always tended toward profiles and features.

I feel like that philosophy permeated the book, that this idea of everybody has a story if you just take time and talk to people, which if I’m honest, I don’t always do in my day-to-day life. I’m often the person sitting in the back of a Lyft with my phone up in front of my face because I don’t want to make conversation with the person driving the car. But I’m not a saint. I’m not perfect. I’m no better than Maddie.

It really seemed important to me that this side of Maddie be shown, but the most important thing is that the person who has to have the first and last say in the book is Cleo.

If there’s one line in the book to single out, it’s when Cleo as a ghost says, “You weren’t interested in my life, you were interested in my death, and they’re not the same thing.”

I think so much of news is about death. Why do we have to wait for someone to die in a particular horrible way to suddenly be interested in their life? And I realized, no, it’s not news.

My dad. . . Now I’m going to get really weepy. I managed not to burst into tears when I talked about Rob, but . . . My dad had a column the year after his father died. He had a short column in the paper. It was less than six hundred words. It was tight. It was a hard space, and he made it work. He wrote about what is really news, and this was back in the ’80s.

His father had died that previous year, and he looked at the Associated Press’ top stories of that year, like that was the year Bhopal had happened. I guess it was the year of Reagan’s election landslide, the year we’re talking about, 1984. And he then said, what would have been my top story of the year? And he’s like, well, none of these. My dad died last year.

This was a time when people would send out the really chatty end of the year holiday cards about what their family did, and it was very fashionable to make fun of those. But my dad wrote that really was the news of the year, and that’s a column I’ve never forgotten. When my dad died, the Sun reprinted it, and we had it printed up on these beautiful stock cards and gave it out at the memorial service. So, I think that was big influence too.

There’s a story in Cleo long before she disappeared, you know? She’s pretty cool. There’s a story with every single person in the book, and that was sort of the point of the book.

The Battle-Axe Who Covers Labor is my absolute favorite.

She was inspired in part, in a very teeny part, there was a woman who worked at the newspaper, she went on to become a Republican congresswoman. I would never call her a battle-axe, but she was a tough cookie.

It was always fascinating to those of us who covered her as a congresswoman, to think that she was a newspaper woman? I can’t imagine it. But yeah, there were these really tough women. I was very aware of the first generation and a half of women, I would say, who had made newsrooms a relatively normal place for someone like me to enter in 1981. As a female, I didn’t feel like I was breaking any barriers.

You’re right. If the Shitty Men in Media list existed, almost all of my colleagues would be on it because it was a different time, and I don’t have any nostalgia for that, and I say this as someone who — good lord, almost every boyfriend I ever had came out of a newsroom. I dated my boss in San Antonio.

You could do that back then.

I know. Then, it was only a problem because there was that idea of is there perceived favoritism. He wasn’t my direct boss. He sat at the copydesk, but he definitely was someone who supervised my copy.

Everybody did it. I don’t know what life would have been like if it hadn’t been like that, but I can’t be nostalgic about that. I just can’t. I’ve had zero patience for people who try to water down their response to #MeToo by saying, “Don’t people get to flirt anymore? Don’t they get to smile at each other? Can’t you compliment someone?” Yeah, I don’t know. I’m not too worried about that. I don’t feel like it’s a big loss.