In 2006, activist Tarana Burke coined the phrase “#MeToo” to foster empowerment among women of color who had been sexually abused. Over a decade later, the phrase evolved into a viral hashtag, popularized by actress Alyssa Milano in the wake of an explosive investigation into claims of sexual misconduct against Harvey Weinstein. “If you’ve been sexually harassed or assaulted write ‘me too’ as a reply to this tweet,” Milano said on Twitter.

Two years since then, it appears that the #MeToo hashtag spawned a global movement against sexual abuse, systemic power imbalance, and ultimately, patriarchy itself.

The Senate hearings for then-Supreme Court nominee Bret Kavanugh, himself credibly accused of sexual assault, proved a test for gauging how much #MeToo had (or hadn’t) changed society’s tolerance for rapists in positions of power. In those hearings, Dr. Christine Blasey Ford, who credibly accused Kavanaugh and his friend of raping her at a party when they were teenagers, was asked what she remembered most about the incident. “Indelible in the hippocampus is the laughter,” she said. “The uproarious laughter between the two, and their having fun at my expense.”

The horror and calm clarity of Ford’s recollection was a stark contrast to Kavanaugh’s bumbling, defensive performance. We all know what happened next: Ford’s testimony was not enough to convince right-wing power brokers that their frat bro Kavanaugh did not deserve the highest bench in the land. The aftermath was collective trauma among women, particularly those who had suffered sexual assault themselves.

“For me and most women I know, that [hearing] was just brutal in ways I think many women couldn’t even fully articulate,” author Shelly Oria told me. “It was just an incredibly painful experience and of course we felt like we had to respond to that in some way.”

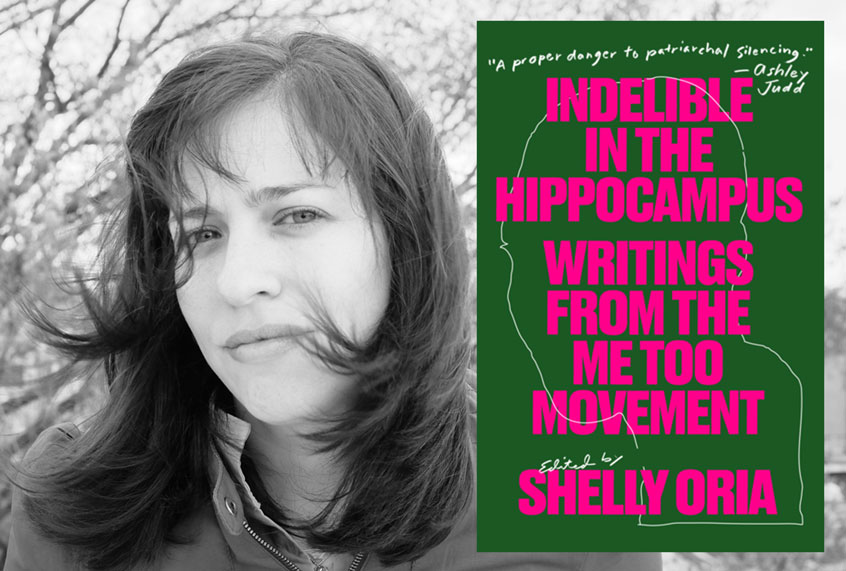

That response took the form of “Indelible in the Hippocampus: Writings From the Me Too Movement,” an anthology edited by Oria that brings the digital #MeToo movement into book form. The anthology includes stories told through various genres — fiction, nonfiction and poetry — from all women.

The book was already in process when the Kavanaugh hearing happened, Oria says. “We had already compiled all the pieces at that point, but that’s when [we] chose the title with that in mind, because we did sort of want to nod both specifically to Dr. Ford, and to her bravery and sacrifice.” Salon sat down with Oria to talk about the book’s origins, the Kavanaugh hearings, and the general state of the #MeToo movement and feminism today. This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Nicole: Let’s first talk about the structure of the book because it’s an anthology. So it’s all of these separate stories, but it makes up one bigger one, and as the editor I imagine there was a lot of careful thought that went into piecing together this larger story. What was important to you?

Shelly Oria: Part of what was important to me about the overall story that we’re telling is that it’s as inclusive in all possible ways, and of course part of the more obvious ways is in just a variety of voices. And that something that I touch on a lot in the foreword, and that’s also pretty obvious from our list of contributors. But I’m also really excited about this idea of the multi-genre that the book offers. It is fiction, nonfiction and poetry, and that matters a lot to me, and was an idea that was sort of a part of the DNA of this book from very early on. We want to expand the conversation to all art forms that can shed different kinds of light on the topic, but also in a more practical way. I think when we’re only publishing nonfiction, we’re also by definition limiting a lot of poets, fiction writers, playwrights who don’t write or don’t feel comfortable, especially with this topic, so we’re also limiting the variety of voices that can be included in this conversation.

I don’t want to spoil too much, but it starts with trauma and it ends with murder. Those are very different subtopics to be included in this anthology.

It does start with kind of a heavier, meatier emphasis on trauma then maybe later on in the book or in some of the pieces more so than others. I think that was another thing that we very much wanted to create a balance on is the type of experiences that we explore this book—from trauma of the worst kind to everyday trauma that all or most women experience every day of our lives, et cetera. And also, I’m very happy with and proud of the diversity and range of styles as well. And that’s, you know, we have cases that are more like think pieces that will really kind of fuck with your thinking if you let it. There are also some that go into the trauma and then the next paragraph will give you like the funniest moments.

And it ends with a fictional short story about murder written by you.

And so that’s another thing is that diversity and then yeah, going from sort of trauma to murder has come up in various ways in Q and A’s and stuff. You know, we have no control over work and over what sits out there world, so the readers who may, despite what I say in the foreword, read this as sort of a call-to-action for women to murder men. For what it’s worth, that is not what I am doing and that is not what that story is doing. For me, I think that’s part of why the story is placed where it is in the book, and does serve of complete an arc in our minds, but it isn’t in that sort of obvious way.

To me part of the murder is murder in the sense that it’s about the rage that we all have to swallow. But part of it isn’t, and that’s what I’m saying and it’s maybe a little reductive or whatever to explain that, but to me it’s this metaphor for the necessity or the possible arguable necessity to erase, deconstruct, dismantle existing structures.

Something that really stuck out to me in the book too was the role that silence plays, and how the pain of sitting in silence too was really clear in some of the stories. Was that intentional?

Yes, we’ve talked so much about silence in all ways and I will even say you and I, before you started recording, touched on the fact that the galley is so much smaller and thinner than the actual book.

And part of the reason why, as I mentioned, is because of one essay that didn’t make it into the galley, but most of it is because of bookmaking and how you sort of determine how much space you give between pieces. And that’s when the conversation of silence was even bigger. Like we really thought of where is silence on the page, sort of punctuated, and allow that silence to sink in with the reader. Where is that crucial? And there were a lot of places and that’s the sort of thing where it’s okay not to do that for the galley but for the book it felt important to everyone involved to really give space to that silence.

Also, to me part of the murder is murder in the sense that it’s about the rage that we all have to swallow. But part of it isn’t and that’s what I’m saying and it’s maybe a little reductive or whatever to to explain that. But to me it’s sort of this metaphor for the necessity or the possible arguable necessity to erase, deconstruct, dismantle existing structures. Like it raises a question from me of how do we correct this and do we need to sort of glue in existing structures.Sort of the basic idea of radical feminism, right? Like we cannot correct it within existing structures. Do we need to dismantle the existing ones in order to make room for the new in order to start over? And I’m not saying there is, but that’s sort of the question in my mind that this narrator is-

What was it like taking this digital movement and putting it into a different medium?

On the one hand I’ll always, until the day I die, will be thankful to this hashtag, thankful to this revolution that started on the internet, thankful to the space it gave to so many women to tell their stories, the strength that gave them and on and on and on. I can go on so long about it. And yet, when you think about almost anything that has mattered, especially if you think of actual revolutions, anything political that has transpired, that has made a difference in our world from even though you know, let’s say the 1970s when the internet started slowly tiny, tiny steps to become what it is now. But even when you really think about just the last 10 years or so in terms of when social media has started to play a part, the way I see it at least, the internet really is just kind of our rehearsal space, if you will, or like where a lot of stuff happens so that it can happen in the physical world.

At the end of the day, if it doesn’t translate then nothing really happened, or maybe I shouldn’t say nothing has happened, but it is not the kind of effect that it can, that can take place in legislation that can take place in regimes changing, that can take place and like the actual things that matter have to move into the physical world have to translate.

What was it like finishing editing this book when the Kavanaugh hearings were finishing?

Kavanaugh happened about middle of the way through, I think. That one is — I don’t know about you, but for me and most women I know that was just brutal in ways I think many women couldn’t even fully articulate it was just an incredibly painful experience and of course we felt like we had to respond to that in some way.

We had already compiled all the pieces at that point, but that’s when, shortly after that when we chose the title with that in mind, because we did sort of want to nod both specifically to Dr. Ford, and to her bravery and sacrifice.

What role do you hope that this book plays in this movement and in feminism in general?

Yeah, these little tiny topics. There’s so much. I don’t know that any of what I’m about to say is going to happen, but if we’re really sort of asking this through the lens of my hopes, one hope is that it engages some readers that that otherwise or until now have not been interested in this conversation. And what has been most kind of uplifting, I don’t know if that’s the right word, but to me in the last few months is that I have heard from quite a few specifically white straight men, CIS men, saying they were really excited for Indelible to come out because something about the book struck them as interesting. Usually it’s just a few writers that they admire that they’ve noticed on the list. And I also want to say a huge part of what I’m hoping for this book, maybe even more than what I’ve said until now is the other part is that… is the women. So many women who did speak up in their own way, even by telling one friend two years ago and even the women who haven’t yet spoken up, who have been hearing all this bullshit about how the Me Too movement gone too far and all of that since, that a lot of us out there, including publishing houses and et cetera, et cetera, are committed to continuing this conversation and actually think that the movement has not yet begun to do what it should do and can do.

# # #

“Indelible in the Hippocampus: Writings From the Me Too Movement,” edited by Shelly Oria and published by McSweeneys publishing, is on sale now.