After finishing her PhD in Stanford University’s Emmett Interdisciplinary Program in Environment and Resources, Lauren Oakes still had questions about how we live in the throes of the climate crisis. Oakes was one of the foremost experts on Alaska’s troubled yellow cedars — trees that are dying due to reduced snow, shallow rooting, and other climate change-related effects. Their prognosis, she found, was grim.

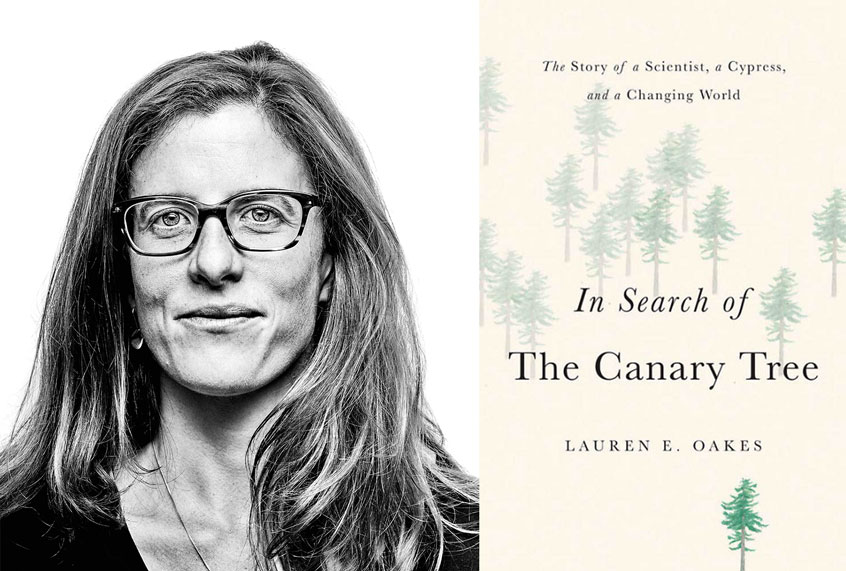

“What was lingering for me was, how do I really cope with that in my daily life? How does that shape my future outlook?” she told Salon in an interview. This self-inquiry led her to write a book, “In Search of The Canary Tree: The Story of A Scientist, a Cypress, and a Changing World,” which was published last fall. The book puts a human face on our planet’s biggest crises, showing how local action can make all the difference moving forward.

Salon interviewed Oakes before her presentation at Original Thinkers in Telluride this year.

I’m wondering if you can share more about your background and how you became both a conservation scientist and a writer.

I’ve always been interested and intrigued by environmental issues, like how [humans] are changing the planet. Even when I was just a kid, it was intriguing to me. So that’s been my long-term interest, and over 20 years I’ve worked on a range of environmental issues. But I also think that when we see change occurring in any arena — whether you’re talking about environmental issues, health issues, or any real social cause — I think that they come from both science and understanding, and also storytelling and getting that information to the people who can use it, who can be motivated from it and put it into action.

So over the years I’ve worked on a lot of research projects, and I’ve been trying to do both — communicate them in compelling ways and come up with some solutions to some of the problems we’re facing today. I was as a trained as an interdisciplinary scientist — I went to a program called the Emmett Interdisciplinary Program In Environment and Resources that’s at Stanford, that’s where I received my PhD. [That program] is really focused on bringing together disciplines to address problems. My training is a blend ecology, land use change, and the social sciences.

Your book, “In Search of the Canary Tree,” derived from your PhD, correct?

Yeah, it’s funny. I always have a hard time answering that question because it’s like, did you translate your thesis into a different language? And no, I did not. But I think what happened for me was that when I got to the point of defending my PhD, my papers were about to be published and there was something still unresolved for me. And I actually believe writing is an act of discovery, right? And I felt like what I needed to figure out was that unresolved piece. And it was a question. I had become one of the most knowledgeable people in this knowledgeable pool of studying some pretty dramatic impacts. And what was lingering for me was how do I really cope with that in my daily life? How does that shape my future outlook?

So the book became a story totally drawn from my research, and I published it in a more accessible way: through story.

And that story is told through the lens of the yellow cedar. I’m wondering if you can share what it is about that tree held your interest for such a long span.

I did spend six years and then two more writing this book. I’m obsessing over a single species, which is pretty weird. […] Back then when I was starting my work, I thought of it as a kind of a looking glass into the future … I thought maybe by going to a place [like Alaska] that was heavily impacted, I might be able to learn some lessons applicable elsewhere.

I thought of [the tree] as a looking glass into the future, and to what other kinds of impacts we might see. I thought maybe by going to a place that was heavily impacted, I might be able to learn some lessons applicable elsewhere. It gave me a really good jumping off point to say, okay, well what happens next after these trees die? What are the impacts to the surrounding plant communities, this ecosystem and to people that have relied, used and valued these trees in various ways. I think all those factors together made it a really compelling species for me when I never thought I’d be be someone studying a tree species for six years.

How was doing your research for your PhD project different than the research for the book?

I was wearing two hats, or started to be more like a reporter going back and talking to other scientists about how do they live with what they know, and what do they think about the future, and what do they do differently in their lives. It’s a mix for me in the writing process. In academic research you’re relying upon all those who have come before you and other published work and common methods, and in storytelling and in nonfiction work, there’s a lot more reporting and a mix of sources that go into it.

What are the similarities you noticed between being a scientist but also being a reporter and a journalist?

Good question. The part I love about it for them both is that you go in with a question that you feel is important, or you know is important, and then you get to rely upon all these other sources of information to make sense out of it and to reconcile and to report what a truth is or what a reality is. And I think there’s all kinds of academic philosophy on what is truth. But I feel like both of them are going in with a non-biased perspective, a question and information to be delivered. And I think the main difference is, I’ve taught some workshops to scientists on storytelling and science, because it kind of bothers me when we think about it as activism. I don’t think it is just taking your science and telling it in a different way. You think of Galileo, who spent so much time making engravings to present his discoveries. That was an art, right? But that was also a science behind it. So I think there are a lot of parallels between the two.

You talk a lot about how local action matters. And I’m wondering if you can give more specific examples of what that means.

I think a lot of where my energy goes now is on local adaptation. So like I said, even if we stop emissions, we’re going to continue to see impacts coming. And that can mean anything [from] impacts to your water resources to fires in a community. So I think step one is starting to learn about what are the impacts expected in your community? What does that mean for your life, for your family? If you’re a farmer, that may mean changing your growing season. If you’re depending on where your water comes from, that maybe your town or, or municipality, considering future plans for that. If you’re living on a coast, what does that look like for the, for the coastal population.

You’ve talked about how the separation from nature stems from our early efforts to protect that, and it seems like we’re still acting with that model. When it comes to conservation today, I’m wondering how you think we can move from the separateness to more of a sense of connection with nature.

Yeah, it’s a great question, and it’s funny to talk about because I think it’s hard even in writing about it that, you’re then perceived as a tree hugger or this green leftist.

But I actually really think that part of the problem is not recognizing that human and environmental health are deeply intertwined. It also makes sense in terms of history. In terms of how development has happened and how land use change happened that we were quite fortunate that at those times we’d be able to create protected areas. The argument that came from some of the people I interviewed [is] that, by [setting aside] those protected areas and by marking them as a boundary, we separated people from the environment.

I consider it more of a scientific fact that, by treating nature as this completely separate protected area, we deny the existence, deny the truth that we rely upon a functioning ecosystem — where our food and our water and our air comes from. They are inherently intertwined.