Rebecca Solnit is one of those increasingly rare writers who manages to avoid the pigeonhole, even as many an article about her reduces her to being the inspiration for the coinage “mansplaining,” which was based on an essay of hers where she describes a man trying to explain her own book to her, while not acknowledging that she wrote it. But as that essay indicates, Solnit is not just a feminist writer, but a historian, and an environmentalist.

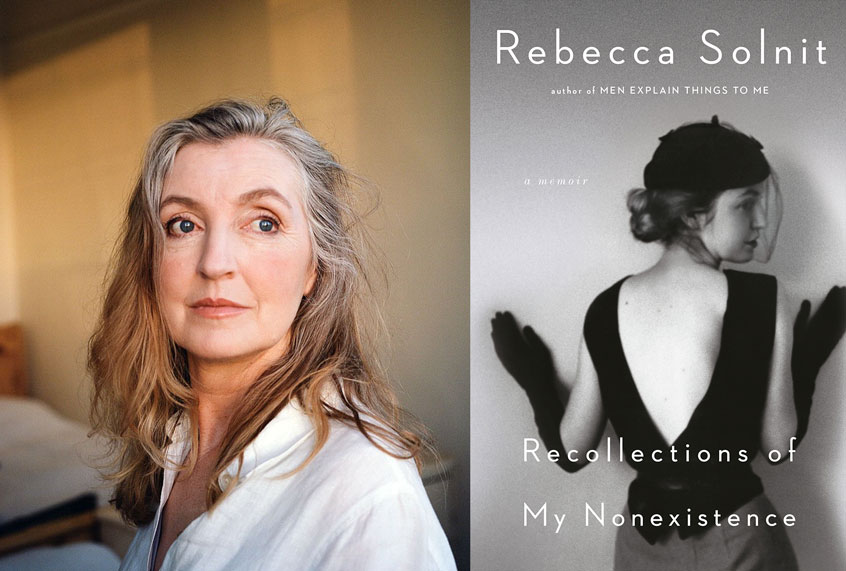

Her latest book, “Recollections of My Nonexistence,” is billed as a memoir, but draws deeply on this broad range of interests to produce something more. Solnit’s remarkable ability to tie her personal stories to the world around her is why she continues to be popular with book buyers, no matter what she writes. Salon spoke with Solnit about her book, punk rock, and what it means for women to write memoirs.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

A couple of years ago I was asked to talk to some young writers, mostly women, about being a writer, and the advice I gave them was to not write about themselves. Women get boxed into being these personal writers and not treated as experts on subject matters. But you write memoir, and this book is a memoir, but you manage to defy that reductive categorization. What’s your secret? What should women do, if they do want to write about themselves but not only about themselves?

First of all, I’m a person who’s written about a lot of other things, environmental and Western and urban histories and various other people and so forth.

But I think there are so many ways to write about oneself. In my last book, “The Faraway Nearby,” and in this book, I’m really interested the conventional definition of the self that is so standard in memoir. I think we’ve all learned to tell a story partly from what I call “therapy culture,” which isn’t therapy at its best. It filters down into a not-always-helpful body of assumptions, to tell a story that is very much focused on us as isolated and unique individuals whose experiences are personal and whose solutions are personal.

I say, very explicitly, in this book that the kind of violence that I was confronting as a very young woman was not a personal problem. There was nothing I had done wrong. There was nothing I could do right to make violence against women go away.

Not only because even women who do everything right — wear habits and never leave the house after dark and never touch a drop of alcohol — get raped along with babies and grandmothers, but also because we’re not separate.

I am impacted by the fact that the desk on which I’ve written all my books was given to me by a friend whose ex-boyfriend tried to murder her and nearly succeeded. I am impacted by the stories I read every day about violence against women. I am impacted by my father’s violence against my mother before I was born.

There is no personal solution to this. I’m not getting over violence against women. It is not my job to psychologically reconcile myself to horrific human rights violations, degradation, threat, menace, insults, exclusion and et cetera.

So there’s a quality of anti-memoir to this book, in that I was focused on how it’s not a personal problem and doesn’t have a personal solution. All of our stories exist in context. What happens to you, happens to you because of your race, and gender, class, the historical moment in which you’re born and various other incidents of fate, whether you’re able bodied, conventionally, beautiful, cisgender and a million other things.

A lot of memoirs have been written by straight white people, who are not always that clear on how specific their experiences are. Straight white men, in particular, tend to think their experiences is the universal human experience.

We are not only the self-contained, largely fluid self inside this held in by our skin. We are all the stories that have ever shaped us, including the stories that imprison us and tell us we’re worthless, and other people matter more than us or the stories that liberate us and bring us joy and insight.

This book is about the drumbeat of violence that women face in our lives from harassment to outright rape and murder. People have been talking about this problem since the beginning of feminism. A lot of people feel like the #MeToo movement is a breakthrough that can really change things, that this time we may actually be kicking the ball down the field a little bit. How do you feel about that? Should we feel hope?

Yes! As I say in the book, that I find I had been waiting my whole life for us to have these conversations about the reality of these things, how and why they happen, the 10,000 reasons why we can get over blaming victims and what some of the solutions might be.

I truly feel I’ve been waiting my whole life, or at least from the time I was a very young woman. I don’t say “harassment,” which always sounds relatively innocuous, but menace, because I don’t care if somebody says something nasty to me.

Okay, I do care, but with none of these incidents did I feel like, oh it’s just some guy telling me something kind of degrading. There’s always a question of, will there be bodily injury? Will there be bodily invasion? Will there’ll be bodily death? In some of these circumstances.

So much of what I write about is not just that some men were menacing me, but that nobody else took it seriously. Nobody else said this is a war against woman. This is an epidemic.

Power had shifted some unseen way. We’re able to have a conversation that we had not had before about how pervasive this is, how impactful it is, and how wrong it is and what exactly it is that happened and how connected all these things, harassment, domestic violence, rape, murder, and the rest are really part of the same pattern of misogyny.

A lot of things that are officially “non-violent,” but are also aimed towards reducing the space in which women can exist. Reducing our right in capacity to be full participants in free and equal citizens.

So even though it’s been a conversation about the ugliest and worst things, just the conversation is exhilarating for me.

Let’s talk about Elizabeth Warren. Your book — your writing in general — intertwines the personal and political so well, and I think it’s particularly important to a lot of women right now, because they’re mourning the loss of Elizabeth Warren from the presidential race. Why does this loss feel just so personal for so many of us?

I think there is a sense with Elizabeth Warren — with seeing a woman who is so qualified, so devoted, so excellent in every possible way — can’t do as well as men who are her inferiors, not because of anything within her control, but because of double standards, of discrimination, of malice, misrepresentation, exclusion, silencing, animosity, as it happens to all of us. So it does feel really personal.

That said, I joked in a piece I did in April that who the hell thinks Warren’s not relatable? I am a wonky blue-eyed, blonde, middle-aged lady and no one has ever been more relatable, likable, and electable to me ever. I feel like I love Elizabeth Warren, the person from what I see of her, from the campaigns and the record and those plans.

My greatest grief is for what could have been, having an intersectionally brilliant, profoundly compassionate, genius listener, administrative rock star, who understood the legal system, the governmental system, and economic system more than everybody else who ran for president in the last 50 years put together. Which might be a mild exaggeration but mild. What she could have done.

For me, it was probably 25% for Elizabeth Warren the person, and 75% for the Elizabeth Warren administration.

I’m tickled to note that you are a punk rock fan, that it was a formative part of your life. I’m also an enormous punk rock fan, but as much as I love it, I still feel like it was a sexist of a scene as any.

Maybe not so much anymore. I talked to somebody this week whose daughter is going to Gilman Street Project, which is a moderately famous old longtime punk venue. And she says it’s just the kindest, most accepting, inclusive crowd she’s ever been in. And going there alone, she’s never felt safer.

But that wasn’t the punk rock of the early ’80s, although it’s kind of the punk rock of the ’70s. I was into punk rock in early 1977 when I was 15. It suddenly exploded and it was so exciting, and so different. As an angsty, wound-up 15 year old, that was my tempo, not the mellow tempo of Fleetwood Mac and all those stadium bands and stuff.

There was this wonderful period, for a few years, where people didn’t really know what punk rock was. There weren’t any rules because it was still being invented. Safety pins and mohawks and crazy colors and leather jackets and narrow legged pants prevailed as a kind of anti-hippie thing. But who could be a punk and what it meant to be a punk was still undetermined. There were a lot of pencil neck geeks, who are my kind of people.

Then the hardcore bands from Southern California came up, and it felt like the ectomorphs were overtaken by the mesomorphs, all these thick-neck, Henry Rollins jocks. It was the end of slam dancing, which was kind of like electrons harmlessly bouncing off each other, to the gladiator mosh pit.

That was not a place in which women have much status and standing. And it’s not a place where I feel particularly encouraged and invited anymore.

I feel like the history of pop music has that over and over again. I call it the “dudes ruin everything” problem. Dance music was like very feminine, very queer, very multiracial and then it just got taken over by straight white guys, who ruined it.

Way back then, female musicians were so exceptional, like Debbie Harry with Blondie or Chrissy Hynde [of the Pretenders].

One of the major characters in my 2005 book, “A Field Guide to Getting Lost,” was a supernaturally talented young lesbian musician friend of mine, who died at 24. I watched her try and have a music career and how often people just wanted to get into her pants and how little respect she got. If she was a man, she would have been recognized as a genius bass player who could learn everything the first time, and was completely awesome and musically sophisticated.

Then Riot Grrrl and some other things came along. But it hadn’t changed yet when I made my exit, more or less. But it was lovely for awhile there, and one of the many, many subcultures that made up the city that was so much part of my formative experience that I recount in this book.