YOU’VE BEEN HACKED!!

The chilling message flashed across Anya’s field of view, blurring everything else in sight. The twenty-six-year-old account executive stared and listened in horror as a malicious intruder activated her auditory cortex, simulating speech deep inside her brain. The voice was gravelly and heavily digitized.

“Your cloud-connected neuroprosthetic has been compromised, and there’s nothing you can do about it! We now control your personal data stream. Oh, and what a stream it is! So many secrets. So many unclean thoughts. You’re lucky you were hacked by us and not someone less…tactful.

“With the access we now have to your thoughts, we could make you do anything. Anything! You have twenty-four hours to pay $7,000 into the untraceable Cryptex account we will provide you or we will publish all of your deepest, darkest secrets for everyone to see! Ha ha ha ha! Don’t forget, we now know who your family is, and your employer, and your church, and . . .”

The dreadful voice fizzled out, the flashing message disappeared, but Anya’s vision was still heavily blurred. A different, more tranquil voice began activating her auditory cortex.

“Your Neurotector Anti-Intrusion Suite has been activated. Please remain calm and do not move while we complete our scan and remove any unauthorized software from your neuroprosthetic.”

Anya breathed deeply, trying to calm her nerves. Thank heaven she had opted for neuro-protection software a year ago! The rampant increase of new cognitive hacking exploits, from false-memory droppers to this sort of snareware, made it essential.

Anya’s vision suddenly cleared and the security software voice returned. “The intruder has been eradicated, and there are no indications of any privacy compromise through outbound transmission. All altered files and memories have been restored. Have a nice day.”

* * *

To say our world is changing is the height of understatement, yet in so many ways it is the same as it has ever been. There are so many good and well-meaning people in the world, but it only takes a few bad actors to spoil things. Since time immemorial, there have been individuals and groups who have sought to take advantage of others, particularly the weak and the vulnerable. It’s a problem as old as humanity.

But now we find ourselves in a very different era, surrounded by extremely different technologies. These present new vulnerabilities and new methods for exploitation. For all of their amazing benefits, communications and computing technologies have opened the door to nearly as many perils. The future promises more of the same.

“Hacking” is a term and a mindset that has been around since the early days of computing. Early hackers were simply computer programmers interested in solving problems and extending the capabilities of their tools. Making humorous messages pop up on col- leagues’ screens or taking remote control of a keyboard were more mischief than malice. Even the first computer viruses and worms were proofs of concept, developed for better understanding, bragging rights, or both. The perpetrators were basically good guys, computer programmers and hobbyists, who would later be referred to as “white hat hackers” or simply “white hats,” to distinguish them from the more malevolent “black hat hackers” who would soon become so prevalent.

The 1970s and 1980s saw the beginning of a new era of computer exploits. One early example was the Morris worm created by Robert Morris, then a graduate student at Cornell University. Though his software wasn’t written to cause damage, Morris made a mistake in his code that resulted in its spreading mechanism copying itself repeatedly on every infected computer until that system crashed. What had started off as an intellectual exercise to call out UNIX security flaws resulted in the first conviction under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act of 1986.

Computer viruses caught the public’s attention in a way few technology problems do, not least because of their biological parallels and self-replicating nature. Here we suddenly had a technology that could independently grow and move about, causing harm in a manner previously reserved for living organisms. It wasn’t long before a new field grew out of the response to this novel threat: antivirus software.

The antivirus industry expanded rapidly during the 1990s and 2000s. With the development of the World Wide Web, suddenly a growing number of people had a reason to buy a computer. Connecting with others is such a mainstay of the human experience, and suddenly we had a new way to connect! Long before the social media giants of the twenty-first century, the early days of the internet allowed people to communicate by email, join chat rooms, share knowledge in online forums, and exchange files. It was a new frontier, a Wild West of communities, opinions, and ideas.

Of course, these were perfect conditions for spreading the rapidly growing number of viruses, Trojans, and worms that were being written. Some were benign, while others could delete all of your files. Stepping into the breach, early antivirus (AV) software developers like McAfee, Avira, and FluShot offered a response to digital intruders. As new viruses would appear, AV companies would work to identify and eradicate them, first in the lab, then as an automated routine they could add to their programs through downloadable updates. Eventually, updates were being rolled out regularly, providing pattern-matching definitions along with methods of removal and recovery.

Unfortunately, this pattern rapidly turned into an escalating arms race. As virus creators found new vulnerabilities to exploit, the AV developers would respond, leading to still newer methods of attack. The result was a vicious circle that quickly saw both sides become extremely sophisticated. Strategies of evasion and detection grew more deliberate and complex, leading to levels of infection, intrusion, and access previously unimagined. Today, the world of viruses, malware, and cybercrime is extremely lucrative. Accenture estimates that the global cost of cybercrime to businesses in the five years between 2017 and 2022 will be $5.2 trillion. Cybersecurity Ventures projects global damages could be as much as $6 trillion annually by 2021.Whoever is correct, these are enormous costs, and it is small wonder cybercrime is now the preferred method of theft and disruption for organized crime, intelligence agencies, and nations around the world, as well as for corporate spies.

As our computer systems and other technologies have grown in complexity, the number of possible points of access have exploded. Every software at every level, from firmware and operating systems to utilities, add-ons, and apps must routinely issue updates, many of which are in direct response to newly discovered vulnerabilities. Our world of technological miracles and conveniences is also exponentially spreading the ways corporations, nations, and individuals can be taken advantage of.

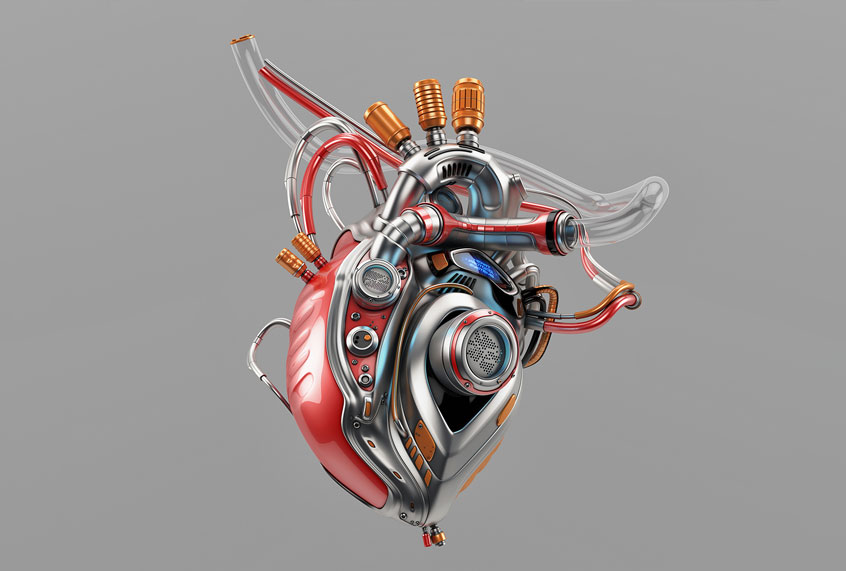

Which brings us back to human augmentation. Every technology that has improved our lives and made them more efficient—smartphones, medical devices, self-driving cars, power plants, phones, ATMs—has proven to be vulnerable to attack. As we increasingly integrate technology into our lives and our bodies, we are setting ourselves up for some very significant dangers.

When we hear the word hacking, we typically think of computers, but the concept and methods are hardly restricted to these devices. Because of this, the term hack has expanded in our society to mean something that alters an object or process from its expected use or behavior. We talk about hacking tools, jobs, human psychology. We even speak of life hacks.

But in our increasingly technological world, it is our digital devices, especially those connected to the internet, that are especially vulnerable. As a result, new emerging technologies such as the Internet of Things, artificial intelligence, and autonomous vehicles are already proving themselves to be prime targets. The physical and mental augmentation of people will only expand the points of potential risk and attack.

For over a decade, I’ve been talking and writing about the risks inherent in implantable medical devices, otherwise known as IMDs. These are devices like pacemakers, neurostimulators, and cochlear implants used to restore hearing. As these grew in popularity and complexity, it became essential to make their software updatable, either through a wired or wireless connection. Unfortunately, this also makes them vulnerable to tampering, especially since for years so many devices did not include encryption to secure them from unauthorized access.

This concern was far from theoretical. In a 2013 episode of the news program 60 Minutes, former vice president Dick Cheney revealed his own experience with this. A longtime sufferer of heart disease, Cheney survived his first of five heart attacks when he was thirty-seven. As a result, the vice president has had several implanted medical devices throughout his later life, including during his time in office. In 2007, after conversations with his doctor and other experts, it was determined the potential for hacking his implanted defibrillator was significant enough that they disabled its wireless feature, the fear being that someone gaining access could alter the defibrillator’s program and shock the vice president’s heart, inducing cardiac arrest.

This is far from the only threat of this type. In 2011, McAfee Security researcher Barnaby Jack demonstrated a wireless hack of two insulin pumps from three hundred feet away. One belonged to a diabetic friend, and the other was set up on a test bench. Without prior access to serial numbers or other unique identifiers, Jack took complete control of each unit. He then instructed the demonstration pump to repeatedly release its maximum dose of insulin until its entire reservoir was empty. Had that pump been attached to a person, it would have quickly resulted in their death.

Today, the news is filled with similar demonstrations, with researchers, hobbyists, and hackers taking control of every type of device imaginable. In 2007, a Jeep SUV was hacked through its Wi-Fi, allowing researchers to take control of multiple systems. Drones have been hacked and intentionally crashed. A test cyberattack on a diesel generator at Idaho National Laboratory in 2007 resulted in its rapid self-destruction.

What all of these disparate hacks have in common is connectivity, in that each has been accessible via the internet, Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, or other radio frequency transmission. The vast majority of hacking incidents over the past several decades have been possible only because of our increasingly connected world.

So, as we put more and more of our devices, our information, and our lives online, they become not only appealing targets for hackers but more attainable as well. The more points of access and connection there are to a device, the greater the likelihood it will be improperly secured. In a highly connected world, every piece of information and every point of access has value. This is not necessarily because you yourself are so appealing to the hackers, but because your information or access may make it possible to infiltrate other, far more lucrative targets. But even if you are not the primary target, such dealings can still do great damage to your equipment, your finances, your reputation, and even your life.

This sets the stage for the state of hacking in our increasingly intelligent twenty-first century. What sort of risks are we likely to encounter? What safeguards can we take to protect ourselves? How are the threats of cybercrime likely to evolve and transform over the next eight decades?

As technology advances, there will be many different ways to hack a person: electronically, biologically, and psychologically. Already there are countless hacks of human psychology, many of which have a very extensive history. Magicians and illusionists have long used a number of techniques including misdirection, deception, and reframing of perception. Such techniques leverage aspects of our cognition that evolved to make certain types of classifications and associations more efficient. Activate a certain expectation, and the mind often doesn’t see many unrelated actions.