Thousands continue to die each day in the United States from COVID-19, and there’s no sign yet that the virus will fully retreat anytime soon. But new analysis from two epidemiologists published in the New York Times on Thursday showed that it didn’t have to be this way. Had the country acted sooner, it could have dramatically decreased the death toll.

And President Donald Trump, as the person best positioned to lead a national response to the crisis, should get the brunt of the blame for this failure.

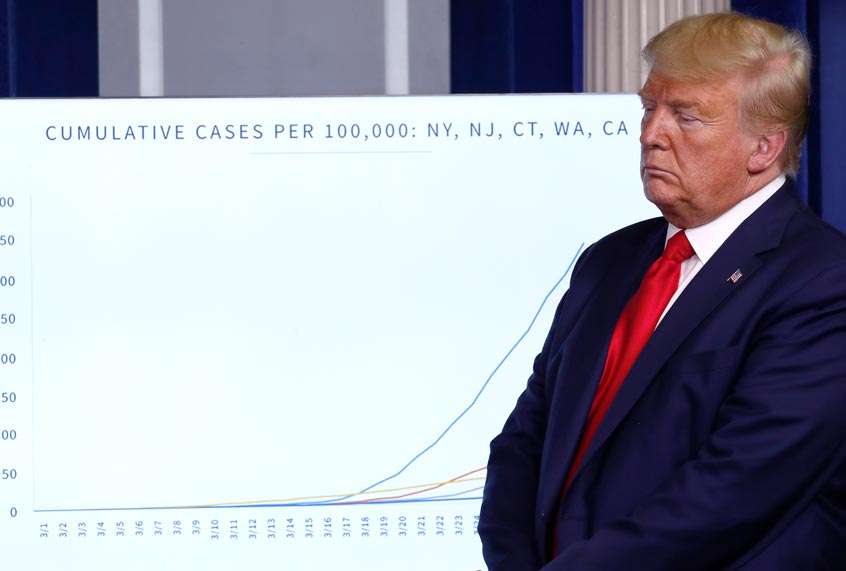

The analysis by Britta and Nicolas Jewell of Imperial College London and London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, respectively, makes use of the fact that viruses spread exponentially. Because of this fact, the social distancing measures we’ve put in place in the United States to quell the spread could have had a significantly larger impact if they had been implemented just a little bit sooner.

“On March 16, the White House issued initial social distancing guidelines, including closing schools and avoiding groups of more than 10,” they wrote. “But an estimated 90 percent of the cumulative deaths in the United States from Covid-19, at least from the first wave of the epidemic, might have been prevented by putting social distancing policies into effect two weeks earlier, on March 2, when there were only 11 deaths in the entire country. The effect would have been substantial had the policies been imposed even one week earlier, on March 9, resulting in approximately a 60 percent reduction in deaths.”

They added: “To determine the impact of early interventions, we used growth rates in cumulative deaths calculated by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington from the date that social distancing measures were introduced until the predicted end of the epidemic, and applied them to case numbers from earlier points when such measures could hypothetically have been put into effect.”

In addition to this modeling, comparative cases show the consequences of policy:

There is no need to rely on the hypothetical calculations that we have described. The recent divergence of epidemics in Kentucky and Tennessee shows that even a few days’ difference in action can have a big effect. Kentucky’s social distancing measure was issued March 26; Tennessee waited until the last minute of March 31. As Kentucky moved to full statewide measures in reducing infection growth, Tennessee was usually less than a week behind. But as of Friday, the result was stark: Kentucky had 1,693 confirmed cases (379 per million population); Tennessee had 4,862 (712 per million).

The pair is careful to say they’re not blaming anybody for this failure; they’re explaining the effects of interventions so we can make better choices in the future.

But voters and political observers don’t need to be circumspect about blaming their leaders for policy failures. In fact, it’s important that we hold them to account as soon as possible. If politicians know they will be judged on their actions and failures to act, they may be less likely to make serious mistakes. And if they do make serious mistakes, calling these out in real-time will give the country the best shot of responding to their ineptitude by ousting them from office whenever the opportunity arises.

And the timeline is damning for Trump. If it had been impossible to see the scale of the crisis coming, the White House’s failure to issue strict guidelines sooner than March 16 would be understandable. But as the Times has documented in a previous in-depth report, the White House had plenty of warning:

A memo dated Feb. 14, prepared in coordination with the National Security Council and titled “U.S. Government Response to the 2019 Novel Coronavirus,” documented what more drastic measures would look like, including: “significantly limiting public gatherings and cancellation of almost all sporting events, performances, and public and private meetings that cannot be convened by phone. Consider school closures. Widespread ‘stay at home’ directives from public and private organizations with nearly 100% telework for some.”

The memo did not advocate an immediate national shutdown, but said the targeted use of “quarantine and isolation measures” could be used to slow the spread in places where “sustained human-to-human transmission” is evident.

But that memo was never turned into policy. Why? Because Trump didn’t want to hear the truth:

Mr. Trump was walking up the steps of Air Force One to head home from India on Feb. 25 when Dr. Nancy Messonnier, the director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, publicly issued the blunt warning they had all agreed was necessary.

But Dr. Messonnier had jumped the gun. They had not told the president yet, much less gotten his consent.

On the 18-hour plane ride home, Mr. Trump fumed as he watched the stock market crash after Dr. Messonnier’s comments. Furious, he called Mr. Azar when he landed at around 6 a.m. on Feb. 26, raging that Dr. Messonnier had scared people unnecessarily. Already on thin ice with the president over a variety of issues and having overseen the failure to quickly produce an effective and widely available test, Mr. Azar would soon find his authority reduced.

The meeting that evening with Mr. Trump to advocate social distancing was canceled, replaced by a news conference in which the president announced that the White House response would be put under the command of Vice President Mike Pence.

The push to convince Mr. Trump of the need for more assertive action stalled. With Mr. Pence and his staff in charge, the focus was clear: no more alarmist messages. Statements and media appearances by health officials like Dr. Fauci and Dr. Redfield would be coordinated through Mr. Pence’s office. It would be more than three weeks before Mr. Trump would announce serious social distancing efforts, a lost period during which the spread of the virus accelerated rapidly.

Over nearly three weeks from Feb. 26 to March 16, the number of confirmed coronavirus cases in the United States grew from 15 to 4,226.

For what it’s worth, on March 5, while Trump was promoting denialism about the scale of the problem, I echoed experts’ calls for more testing and social distancing.

But the policy failure wasn’t only Trump’s. The Jewells note that New York, where the largest outbreak in the country continues to rage, didn’t have a stay-at-home order until March 22. Political leaders in the state and city deserve serious scrutiny for their delay, which another Times piece documented in detail:

“Flu was coming down, and then you saw this new ominous spike. And it was Covid. And it was spreading widely in New York City before anyone knew it,” said Dr. Thomas R. Frieden, the former head of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and former commissioner of the city’s Health Department. “You have to move really fast. Hours and days. Not weeks. Once it gets a head of steam, there is no way to stop it.”

Dr. Frieden said that if the state and city had adopted widespread social-distancing measures a week or two earlier, including closing schools, stores and restaurants, then the estimated death toll from the outbreak might have been reduced by 50 to 80 percent.

But New York mandated those measures after localities in states including California and Washington had done so.

San Francisco, for example, ordered schools closed on March 12 when that city had 18 confirmed cases; Ohio also ordered its schools closed on the same day, with five confirmed cases. Mr. de Blasio ordered schools in New York to close three days later when the city had 329 cases.

Then seven Bay Area counties imposed stay-at-home rules on March 17. Two days later, the entire state of California ordered the same. New York State’s stay-at-home order came on the 20th, and went into effect on March 22.

“New York City as a whole was late in social measures,” said Isaac B. Weisfuse, a former New York City deputy health commissioner. “Any after-action review of the pandemic in New York City will focus on that issue. It has become the major issue in the transmission of the virus.”

But the federal government is best positioned to both understand a global pandemic as it is emerging and to lay down clear guidelines for the country to fight it. Without this support, it’s much harder for local officials to do what they need to do.